Interesante coyuntura: nivel internacional

THE ECONOMIST ; YELLEN DE LA FED Y EL BANCO CENTAL EUROPEO

YELLEN ON INFLATION

By : Doug Nolan

Global Markets rallied sharply this week. The DJIA rose 223 points to a record 21,638. The S&P500 gained 1.4% to a new all-time high. The Nasdaq100 (NDX) surged 3.2%, increasing 2017 gains to 20.0%. The Morgan Stanley High Tech Index rose 3.4% (up 24.6% y-t-d), and the Semiconductors surged 4.7% (up 21.8%).

Emerging markets were notably strong. Equities rallied 5.0% in Brazil, 5.5% in Hong Kong, 5.1% in Turkey, 2.5% in Russia, 2.2% in Mexico and 2.1% in India. The Brazilian real gained 3.2%, the Mexican peso 3.0%, the South African rand 2.7% and the Turkish lira 2.3%. Global bond markets also rallied. Yields (local currency) dropped 27 bps in Brazil, 18 bps in South Africa, 16 bps in Turkey and 22 bps in Argentina. Here at home, five-year Treasury yields dropped eight bps (to 1.87%). U.S. corporate Credit also enjoyed solid gains. Across global markets, it appeared that short positions were under pressure.

Markets reacted with elation to Janet Yellen’s Washington testimony – widely perceived as dovish. In particular, the chair’s timely comments on inflation were cheered throughout global securities markets. A headline from the Financial Times: “Fed Chair Yellen’s Inflation Concern Buoys Markets.” And Friday afternoon from Bloomberg: “S&P 500 Hits Record as Inflation View Turns Iffy”.

July 12 – Financial Times (Sam Fleming): “Janet Yellen acknowledged… that the US’s persistently subdued inflation could raise questions about the Federal Reserve’s current path of gradually raising interest rates and vowed to watch prices ‘very closely’ for signs they were stagnating. The Fed chair insisted it was ‘premature’ to second guess policymakers’ determination inflation was slowly headed to the central bank’s target of 2%. But her note of caution helped spark a rally in US Treasuries and equities, with investors hopeful Ms Yellen would keep the Fed’s easy money stance for longer… Ms Yellen was broadly positive about the economy’s recent performance…, stressing there had been a rebound in household spending over recent months and the Fed was still anticipating further rate increases. But she also said she was studying the low inflation numbers for signs that short-term drags on prices may not be the only factors holding it back. She added that rates may not need to be lifted a lot more to get back to a neutral stance. ‘We are watching inflation very carefully,’ Ms Yellen said... ‘I do believe part of the weakness in inflation reflects transitory factors, but well recognise that inflation has been running under our 2% objective, that there could be more going on there.’ Analysts said Ms Yellen’s remarks marked a small but significant change of thinking, putting the Fed’s path of gradually pulling back on economic stimulus in question. ‘Yellen’s statement today reveals that the Fed isn’t as sure about inflation as they led us to believe,’ said Luke Bartholomew, investment strategist at Aberdeen Asset Management.”

It’s fair to say that the whole issue of “inflation” confounds the Fed these days. Despite antiquated analytical frameworks and econometric models, the Federal Reserve is showing zero inclination to rethink its approach. At the minimum, objective policy analysis would recognize today’s nebulous link between monetary stimulus and consumer price inflation. Rational thinking would downgrade CPI as a policy guidepost, especially relative to indicators of broader price and financial stability. Still, consumer prices rising slightly below 2% have somehow become central to the argument for maintaining aggressive monetary accommodation.

The nature of economic output has fundamentally changed – from mass-produced high tech hardware, to limitless software and digitalized content, to endless pharmaceuticals and wellness to energy alternatives to, even, the proliferation of organic foods - just to get started. There is today essentially unlimited capacity to supply many of the things we now use in everyday life (sopping up purchasing power like a sponge). Much of this supply is sourced overseas, which further diminishes the traditional relationship between domestic monetary conditions and consumer price inflation.

These dynamics have unfolded over years and are well recognized in the marketplace. To be sure, ongoing tepid consumer price inflation seems to be the one view that markets hold with strong conviction. So when Yellen suggested that below target inflation would alter the trajectory of Fed “normalization,” the markets immediately took notice. When she again referred to the “neutral rate” and implied that the Fed was currently near neutral, this further signaled a Fed that has developed its own notion of what these days constitutes “normal.” Throw in that the FOMC plans to pause rate increases while gauging market reaction to its (cautious) balance sheet operations, and it has become apparent to the markets that the Fed won’t be pushing rates much higher any time soon.

We’ll wait to see if Fed officials push back against the market’s dovish interpretation of Yellen testimony. There’s certainly no conundrum. If the Fed is confused that financial conditions have loosened in the face of “tightening” measures, look in the mirror. Chair Yellen needed to choose her words carefully, especially on the subject of inflation. The markets were near all-time highs, with what has likely been a decent amount of hedging/shorting over the past month. An upside breakout risks a bout of destabilizing speculation. At the same time, there were early indications of fledgling risk aversion. Global yields had recently jumped. Weakness was notable in the periphery debt markets (i.e. Italy, EM), and even U.S. corporate Credit was hinting vulnerability.

Importantly, there was heightened market concern that a concerted effort was underway to begin removing central bank accommodation – that booming markets and stubbornly loose financial conditions might force central bankers to adopt more aggressive tightening measures.

Understandably, the markets will interpret a dovish Yellen – especially the nuanced language on the topic of inflation – as rushing to the markets’ defense. The view that the Fed won’t tolerate even a modest market pullback is, again, further emboldened. And quickly global markets will return to the view that central bankers may talk “normalization,” while their overarching anxiety for upsetting markets has diminished little.

July 12 – Bloomberg (Vivien Lou Chen): “Fed Chair Janet Yellen says that in looking at asset prices and valuations, the central bank is ‘not trying to opine on whether they’re correct’; instead, policy makers are assessing the risk of potential spillovers. As asset prices rise, there hasn’t been a substantial increase in borrowing, Yellen said. [The] financial system is strong and resilient.”

I assume chair Yellen is referring to U.S. non-financial and non-government borrowings. Clearly, central bank Credit and government borrowings have expanded spectacularly around the globe. I suspect as well there has been a major expansion in speculative leveraging and securities Credit at home and abroad.

Georgia Senator David Purdue: “Thank you for being here and for your service. I just have two quick questions. I’m very concerned about global debt. The Institute of International Finance recently reported that their estimate of total global debt is $217 trillion, or more than 300% of global GDP. Do you agree with that?”

Chair Yellen: “So, I haven’t heard that number. That could be. I don’t have that number.”

Purdue: “Of that, $60 trillion is estimated to be sovereign debt. We have about $20 trillion of the $60 trillion. With that as background, the four large central banks also have their largest historic balance sheets. Japan, China, EU and US have collectively close to approaching $20 trillion now of balance sheet size. As you talk about reducing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, are you coordinating with these other central banks and looking at emerging market debt - particularly the $300 billion that’s coming due by the end of 2018 - relative to the size of your balance sheet here in the United States?”

Yellen: “I wouldn’t say coordinate. We try to make sure we meet regularly and discuss our policy approaches; to make sure that central banks understand how we are looking at economies and policy options. I think the major central banks understand the approach that others are taking. But trying to ask in an aggregate sense how much debt is outstanding is something we’re not doing. Our economies are in rather different situations. While we all encountered weaknesses that were sufficiently severe that Japan, the ECB, the Bank of England, the United States, we all resorted to purchases of longer-term assets to support growth. It leaves the Bank of Japan and the ECB.”

Purdue: “Are you concerned about so much of that [debt] denominated in dollars today?”

Yellen: “It is a risk. A significant amount of that is in China, but that’s not the only country where there are substantial corporate dollar-denominated debts. And certainly that is a risk that we have considered that affects the global economy.”

Senator Bob Menendez: “Let me ask you finally, how does—we see high rising levels of household debt, widening inequality, a neutral interest rate at historically low levels. To me, it’s critical that the Fed has the ability to respond in the event of another economic decline. How does below target inflation impact household debt? And what signs do you see of inflation coming close to the Fed’s 2% target, let alone exceeding it by dangerous amounts?”

Yellen: “As I said, I think the risks with respect to inflation are two-sided. But we’re very aware of the fact that inflation has been running below our 2% objective now for many years, and we’re very focused on trying to bring inflation up to our 2% objective. That’s a symmetric objective and not a ceiling. We know from periods [when] we’ve had deflation, which of course we don’t have in this country. But that is something that has a very adverse effect on debtors and can leave debtors drowned in debt. Now, we don’t have a situation nearly that serious. But it is important when we have a 2% inflation objective to make sure that we achieve it and we’re focused on doing that.”

Yellen stated during that the Fed’s inflation mandate is “symmetrical.” Yet it’s unimaginable that the FOMC would keep monetary conditions extraordinarily tight for nine years in response to CPI modestly above its 2% target?

It’s by this point abundantly clear that contemporary monetary management exerts major direct influences on the structure of asset prices, while having dubious effect on aggregate consumer prices. This now discernable dynamic creates a momentous dilemma for central banks. Especially after the worldwide adoption of the Bernanke doctrine, it’s fundamental to their approach that central banks retain the power to inflate out of trouble as necessary. Why fret debt accumulation, speculation and asset price Bubbles when central banks can always inflate the general price level, thereby reducing debt burdens and asset overvaluation?

Central bankers have a penchant for speaking in terms of “fighting the scourge of deflation.” More specifically, they view inflation as the indispensable mechanism for reflating systems out of the consequences of debt and asset Bubbles. If central bankers were to admit they don’t control “inflation,” then their policy doctrine of promoting reflationary debt growth and higher asset prices turns spurious.

It has been my longstanding position that it’s not possible to inflate out of major Credit and asset Bubbles. As we’ve witnessed for years now, central bank stimulus fuels self-reinforcing speculative excess, with a resulting accumulation of speculative leverage and securities-related Credit more generally. At the same time, years of abundant cheap global liquidity work to feed overcapacity and attendant downward price pressure on many things. Rampant inflation within the Financial Sphere nurtures pricing vulnerabilities and instability throughout the Real Economy Sphere. Bubbles Inflate Only Bigger.

As such, if one accepts the reality that central banks don’t control inflation, the policy course of repeatedly inflating serial Bubbles can be viewed as risking eventual catastrophic policy failure. There’s simply no escaping the day of reckoning. This analysis certainly applies to China. Led by strong lending ($214bn), June growth in Total Social Financing jumped to $263bn. This puts first-half non-government Credit growth at $1.65 TN (up 14% from last year’s record pace), consistent with my expectation for total Chinese Credit growth this year to exceed $3.5 TN.

Along with Yellen’s testimony, China developments were likely a factor in this week’s global risk market rally. The view is taking hold that Chinese officials have at least temporarily pulled back from tightening measures, perhaps in preparation for this autumn’s 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

July 12 – Wall Street Journal (Grace Zhu): “Chinese banks extended higher-than-expected volume of loans last month even as growth in the money supply continued to slow amid Beijing’s efforts to reduce leverage in its financial system. New yuan loans issued by Chinese banks surged to 1.54 trillion yuan ($226.38bn) in June, up from 1.11 trillion yuan in May… The volume was well above the 1.3 trillion yuan forecast by economists… June is typically a high point for new credit from Chinese banks’ as loan officers rush to meet quarterly targets. Beyond that, demand for credit from households—mostly for mortgages in the hot property market—remained strong, and companies too turned to banks for loans, instead of issuing bonds.”

July 12 – Financial Times (Gabriel Wildau): “China’s central bank injected $53bn into the banking system on Thursday, the latest sign that policymakers have eased up on a fierce deleveraging campaign that has caused turmoil among lenders in recent months. President Xi Jinping told the politburo in April that ‘financial security’ was a top policy priority for the year. That led the central bank to tighten liquidity, while the ambitious new banking regulator unleashed a ‘regulatory windstorm’ that sent shockwaves through the banking system. The storm appears to be passing, as the People’s Bank of China has become more generous with cash injections while the China Banking Regulatory Commission has delayed implementation of a significant new directive. ‘There are clear signs in recent weeks of monetary and supervisory tightening being eased,’ Tao Wang, co-head of Asia economics at UBS in Hong Kong, wrote…”

The algorithm kingdom

CHINA MAY MATCH OR BEAT AMERICA IN AI

Deep pool of data may let it lead in artificial intelligence.

By: The Economist

AT THE start of this year, two straws in the wind caught the attention of those who follow the development of artificial intelligence (AI) globally. First, Qi Lu, one of the bosses of Microsoft, said in January that he would not return to the world’s largest software firm after recovering from a cycling accident, but instead would become chief operating officer at Baidu, China’s leading search engine. Later that month, the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence postponed its annual meeting. The planned date for the event in January conflicted with the Chinese new year.

These were the latest signals that China could be a close second to America—and perhaps even ahead of it—in some areas of AI, widely considered vital to everything from digital assistants to self-driving cars. China is simply the place to be, explains Mr Lu, and Baidu the country’s most important player. “We have an opportunity to lead in the future of AI,” he says.

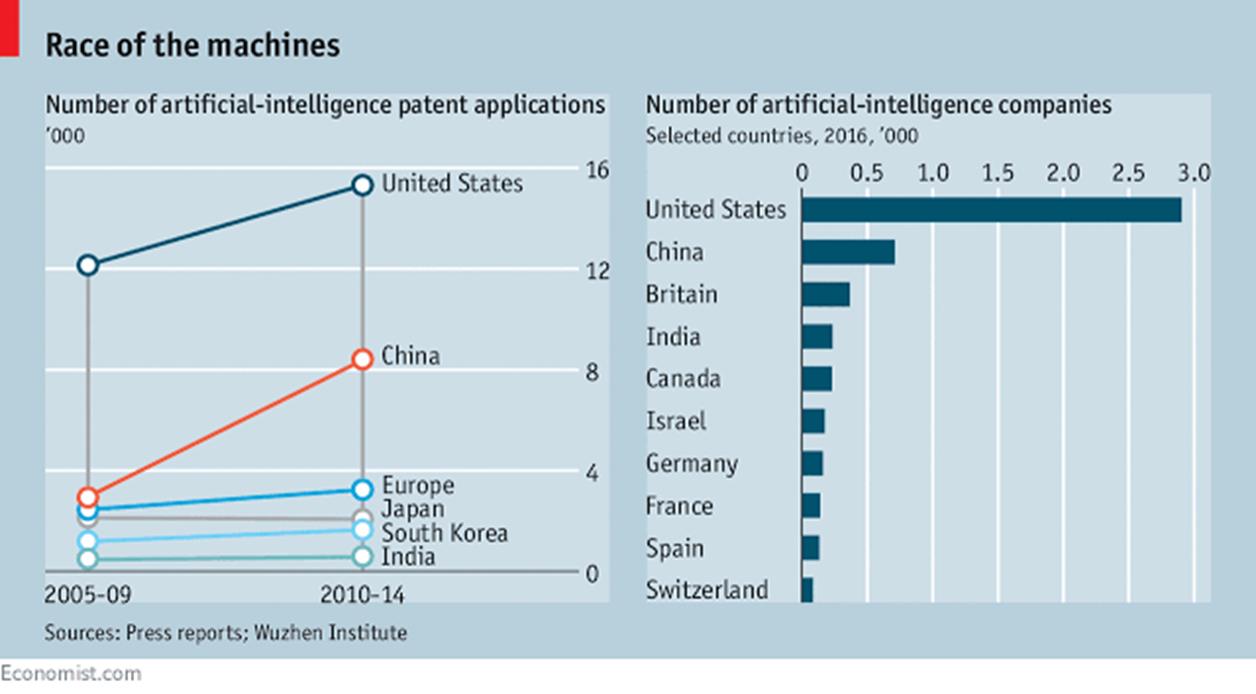

Other evidence supports the claim. In October 2016 the White House noted in a report that China had overtaken America in the number of published journal articles on deep learning, a branch of AI. PwC, a consultancy, predicts that AI-related growth will boost global GDP by $16trn by 2030; nearly half of that bonanza will accrue to China, it reckons. The number of AI-related patent submissions by Chinese researchers has increased by nearly 200% in recent years, although America is still ahead in absolute numbers (see chart).

To understand why China is so well placed, consider the inputs needed for AI. Of the two most basic, computing power and capital, it has an abundance. Chinese firms, from giants such as Alibaba and Tencent to startups such as CIB FinTech and UCloud, are building data centres as fast as they can.

The market for cloud computing has been growing by more than 30% in recent years and will continue to do so, according to Gartner, a consultancy. In 2012-16 Chinese AI firms received $2.6bn in funding, according to the Wuzhen Institute, a think-tank. That is less than the $17.9bn that poured into their American peers, but the total is growing quickly.

Yet it is two other resources that truly make China a promised land for AI. One is research talent. As well as strong skills in maths, the country has a tradition in language and translation research, says Harry Shum, who leads Microsoft’s AI efforts. Finding top-notch AI experts is harder in China than in America, says Wanli Min, who oversees 150 data scientists at Alibaba.

But this will change over the next couple of years, he predicts, because most big universities have launched AI programmes. According to some estimates, China has more than two-fifths of the world’s trained AI scientists.

The second advantage for China is data, AI’s most important ingredient. In the past, software and digital products mostly obeyed rules laid down in code, giving an edge to those countries with the best coders. With the advent of deep-learning algorithms, such rules are increasingly based on patterns extracted from reams of data. The more data are available, the more algorithms can learn and the smarter AI offerings will be.

China’s sheer size and diversity provide powerful fuel for this cycle. Just by going about their daily lives, the country’s nearly 1.4bn people generate more data than almost all other nations combined.

Even in the case of a rare disease, there are enough examples to teach an algorithm how to recognise it. Because typing Chinese characters is more laborious than Western ones, people also tend to use voice-recognition services more often than in the West, so firms have more voice snippets with which to improve speech offerings.

THE SAUDI ARABIA OF DATA

What really sets China apart is that it has more internet users than any other country: about 730m. Almost all go online from smartphones, which generate far more valuable data than desktop computers, chiefly because they contain sensors and are carried around. In the big coastal cities, for instance, cash has all but disappeared for small purchases: people settle with their devices using services such as Alipay and WeChat Pay.

Chinese do not seem to be terribly concerned about privacy, which makes collecting data easier. The country’s bike-sharing services, which have taken big cities by storm, for example, not only provide cheap transport but are what is known as a “data play”. When riders hire a bicycle, some firms keep track of renters’ movements using a GPS device attached to the bike.

Young Chinese appear particularly keen on AI-powered services and relaxed about use of their data. Xiaoice, an upbeat chatbot operated by Microsoft, now has more than 100m Chinese users. Most talk to it between 11pm and 3am, often about the problems they had during the day. It is learning from interactions and becoming cleverer. Xiaoice no longer just provides encouragement and tells jokes, but has created the first collection of poems written with AI, “Sunshine Lost Its Window”, which caused a heated debate in Chinese literary circles over whether there can be such a thing as artificial poetry.

Another important source of support for AI in China is the government. The technology figures prominently in the country’s current five-year plan. Technology firms are working closely with government agencies: Baidu, for example, has been asked to lead a national laboratory for deep learning. It is unlikely that the government will burden AI firms with over-strict regulation.

The country has more than 40 laws containing rules about the protection of personal data, but these are rarely enforced.

Entrepreneurs are taking advantage of China’s talent and data strengths. Many AI firms got going only a year or two ago, but plenty have been progressing more rapidly than their Western counterparts. “Chinese AI startups often iterate and execute more quickly,” explains Kai-Fu Lee, who ran Google’s subsidiary in China in the 2000s and now leads Sinovation Ventures, a venture-capital fund.

As a result, China already has a herd of AI unicorns, meaning startups valued at more than $1bn.

Toutiao, a news aggregator based in Beijing, employs machine learning to recommend articles using information such as a reader’s interests and location; it also uses AI to filter out fake information (which in China mainly means dubious health-care announcements). Another AI startup, iFlytek, has developed a voice assistant that translates Mandarin into several languages, including English and German, even if the speaker uses slang and talks over background noise. And Megvii Technology’s face-recognition software, Face++, identifies people almost instantaneously.

SKYNET LIVES

At Megvii’s headquarters, visitors are treated to a demonstration. A video camera in the lobby does away with the need for showing ID: employees just walk in without showing their badges.

Similar devices are positioned all over the office and their feeds are shown on a video wall.

When a face pops up on the wall, it is immediately surrounded by a white rectangle and some text giving information about that person. In the upper right-hand corner of the screen big letters spell “Skynet”, the name of the AI system in the Terminator films that seeks to exterminate the human race. The firm already enables Alipay and Didi, a ride-hailing firm, to check the identity of new customers (their faces are compared with pictures held by the government).

Reacting to the success of such startups, China’s tech giants, too, have begun to invest heavily in AI. Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, collectively called BAT, are working on many of the same services, including speech- and face-recognition. But they are also trying to become dominant in specific areas of AI, based on their existing strengths.

Tencent has so far kept the lowest profile; it established its AI labs only in recent months. But it is bound to develop a big presence in AI: it has more data than the other two. Its WeChat messenger service has nearly 1bn accounts and is also the platform for thousands of services, from payments and news to city guides and legal help. Tencent is also a world-beater in games with blockbusters such as League of Legends and Clash of Clans, which have more than 100m players each globally.

Alibaba is already a behemoth in e-commerce and is investing billions to become number one in cloud computing. At a conference in June in Shanghai it showed off an AI service called “ET City Brain” that uses video recognition to optimise traffic in real time. It uses footage from roadside cameras to predict the behaviour of cars and can adjust traffic lights on the spot. In its home town of Hangzhou, Alibaba claims, the system has already increased the average speed of traffic by 11%. Alibaba is also planning to beef up what it calls “ET Medical Brain”, which will offer AI-powered services to discover drugs and diagnose medical images. It has signed up a dozen hospitals to get the data it needs.

But it is Baidu whose fate is most tied to AI, in part because the technology may be its main chance to catch up with Alibaba and Tencent. It is putting most of its resources into autonomous driving: it wants to get a self-driving car onto the market by 2018 and to provide technology for fully autonomous vehicles by 2020. On July 5th the firm announced a first version of its self-driving-car software, called Apollo, at a developer conference in Beijing.

Getting Apollo right will not only involve cars safely navigating the streets, but managing a project that is open to outsiders. Rivals such as Waymo, Google’s subsidiary, and Tesla, an electric-car firm, jealously guard their software and the data they collect. Baidu is planning not only to publish the recipe for its programs (making them “open-source”, in the jargon), but to share data. The idea is that carmakers that use Baidu’s technology will do the same, creating an open platform for data from self-driving cars—the “Android for autonomous vehicles”, in the words of Mr Lu.

DRIVE LIKE A BEIJINGER

It remains to be seen how successful Chinese firms will be in exporting their AI products—for now, only a tiny handful are used abroad. In theory they should travel well: a self-driving car trained on China’s chaotic streets ought to have no problem navigating the more civilised traffic in Europe (in contrast, a vehicle trained in Germany may not get far beyond the first intersection in Beijing). But consumers in the West may hesitate to use self-driving cars that have been trained in a laxer safety environment that is more tolerant of accidents. Chinese municipalities are said to be falling over themselves to be testing grounds for autonomous vehicles.

There is another risk. Data are the most valuable input for AI at the moment, but their importance may yet diminish. AI firms have started to use simulated data, including those from video games.

New types of algorithms may be capable of getting smart with fewer examples. “The danger is that we stop innovating in algorithms because of our advantage in data,” warns Gansha Wu, chief executive of UISEE, a Beijing startup which is developing self-driving technology. For now, though, China looks anything but complacent. In the race for pre-eminence in AI, it will run America close.

BANKS ALL ROW IN THE SAME DIRECTION

Central banks are reacting to a global economy moving in the same direction for the first time in years

By: Richard Barley

The central-bank landscape has changed. Divergence is dead, and convergence is in the cards. Such transitions are when things start to get tricky.

The turn in the tide at central banks—whether it be the European Central Bank charting a path to reducing bond purchases, the Federal Reserve preparing to rein in its balance sheet, the Bank of Japan’s stealth tapering, the Bank of England talking of a rate rise or the Bank of Canada actually raising rates for the first time in seven years—has led to speculation about coordinated action. The idea that a secret cabal of central bankers have conspired to work together was dismissed recently by ECB executive board member Peter Praet.

The more likely explanation is simply that central banks are reacting to a global economy moving in the same direction for the first time in years. After a decade of crisis-fighting policy, there is no obvious crisis to fight. Output gaps are closing, and economic volatility is low. The threat of deflation has faded. Inflation is below target in many countries, with the exception of the U.K. But central bankers are generally making the argument that softness in headline measures is transitory, with growth holding up and labor markets tightening.

That shift matters for markets. It tips the balance for future policy actions: economic data would need to deteriorate persistently for a change in tone. And it allows room for central bankers to consider other risks, in particular the steep rise in asset prices that their policies have engendered and which may yet pose a threat to financial stability.

The question is whether markets have taken that on board. This week’s action highlights that.

First, markets put a dovish spin, perhaps unwarrantedly, on Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen’s testimony Wednesday and the “everything rally” resumed: prices for stocks, bonds and gold all rose. But to the extent that markets ease financial conditions, they may actually encourage central bankers to tighten policy. Bonds fell back Thursday after The Wall Street Journal reported ECB President Mario Draghi could signal a shift in policy at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference in Augus

The European Central Bank headquarters in Frankfurt. ECB President Mario Draghi could signal a shift in policy at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference in August. Photo: RALPH ORLOWSKI/REUTERS

Clouding the picture, markets could yet do some of the tightening for central banks, particularly when it comes to currencies. For instance, the ECB may have a problem if the euro charges higher, as a 10% rise in the trade-weighted exchange rate could shave 0.5 percentage point off inflation, notes Lombard Street Research. No wonder the Fed and the ECB are eager to talk about how they will move gradually. The risk to markets is that investors get too comfortable with this idea.

This push-and-pull seems likely to lead to higher volatility. Central bankers have for a long time been investors’ best friends. Now the relationship is a lot more complicated.