NUEVAMENTE : NOTAS MUY INTERESANTES

QUE PROVIENEN TODAS DEL EXTERIOR Y VALE LA PENA ESCUDRIÑARLAS

Por:Dennis Falvy

Financial assets, made in China

CHINA ENTERS THE BIG LEAGUES OF GLOBAL MARKETS

Inclusion in major stock and bond indices will force investors to put cash in China

By : The Economist

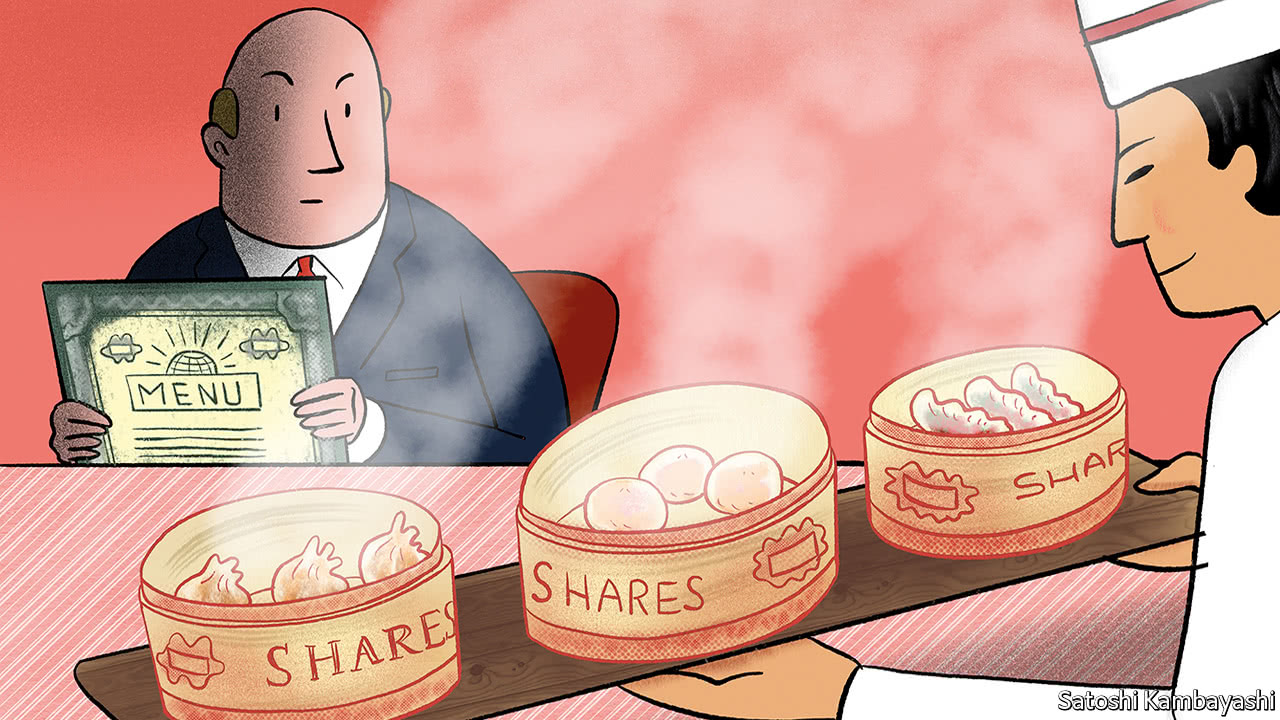

From shoes to shirts and phones to fridges, made-in-China goods have blanketed the globe over the past three decades, entering every country and just about every home. But one kind of Chinese good few abroad dare touch: its financial assets. Outsiders own less than 2% of its shares and bonds, far below the levels of foreign ownership seen in other markets. Capital barriers and financial risks have put investors off. This, however, is changing. The globalisation of China’s capital markets is slowly gathering steam, as symbolised by the inclusion of Chinese stocks and bonds in global indices.

MSCI, a company that designs stockmarket indices, announced on June 20th that it will bring Chinese equities into two of its benchmarks: one that covers emerging markets; and another that follows stocks around the world. To begin, it will include a small number of shares, just 222 of the more than 3,000 listed in China. But its decision matters to asset managers who track their performance against MSCI’s indices or who invest in exchange-traded funds linked to them. They will in effect be forced to allocate capital to China’s stockmarkets, many for the first time. Because MSCI is giving Chinese stocks a limited weighting (0.73% of its emerging-markets index), the resulting cash inflows could add up to only about $10bn next year, equivalent to less than one hour of trading in China’s frenetic markets. Yet the weighting is likely to increase in the coming years.

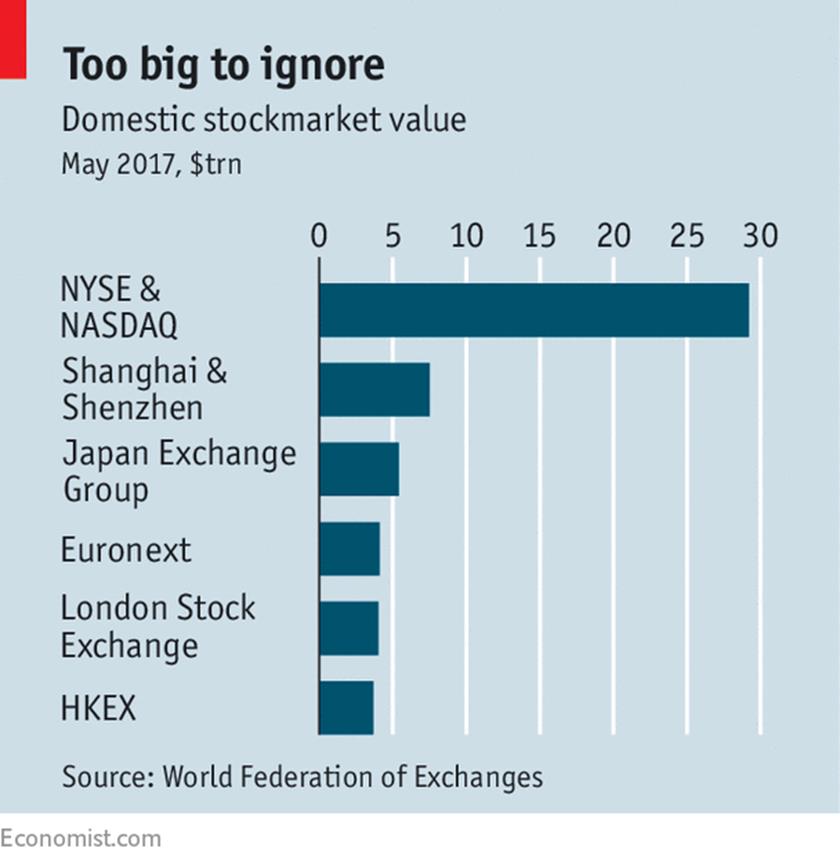

It was a contentious decision, despite China’s size. The country accounts for 15% of global GDP. Its stockmarket, housed in exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen, is the world’s second-biggest (see chart). But for each of the past three years MSCI had debated whether to add Chinese shares to its indices, only to back off each time because of restrictions on foreign investors.

Gaining access to China’s markets was—and is—hampered by formidable obstacles. Because of China’s tightly managed capital account, foreigners can only buy shares through a few quota-controlled channels. MSCI concluded that enough had been done to allay such concerns, largely thanks to a scheme that lets foreigners buy mainland stocks in Hong Kong.

Foreign institutions already hold Chinese shares but until now have mainly focused on firms listed in Hong Kong and America. These overseas Chinese stocks form 28% of the MSCI emerging-markets index. But onshore Chinese stocks are collectively much more valuable.

They also encompass a far wider range of companies. The pensions and university endowments that follow MSCI will now own shares in makers of traditional Chinese medicine and distillers of baijiu, a fiery grain liquor—albeit only in tiny amounts invested passively through index trackers.

Chinese fund managers hope that the MSCI seal of approval might also entice active investors.

“If you like Chinese food, you should go to China and have the real food. It is so much more diverse and authentic,” says Wang Qi, chief executive of MegaTrust Investment, a Shanghai-based fund manager.

But many foreigners still shun the local fare. The stockmarket remains rife with insider trading and price manipulation. Memories of a debacle in 2015, when authorities intervened heavily after a bubble burst, also remain fresh. Chinese regulators are betting that greater participation by international institutions will help bring order.

China’s bond market could prove just as significant in integrating its financial system with the rest of the world. In May the central bank announced that foreign investors would be able to buy onshore bonds via the Hong Kong bond market. This programme, which is expected to start in July, will pave the way for bond indices to include Chinese debt. Again, the gap is glaring: China’s bond market is the world’s third-biggest but is excluded from the main global bond indices. Analysts with Goldman Sachs forecast that inclusion could spark inflows of up to $250bn by 2020. Over the past half year both Bloomberg and Citigroup have started to add China to their emerging-market bond indices.

For China-focused financiers, all this serves as belated recognition. “I’m not saying institutions should have 15% exposure to China. But they should certainly have somewhere north of zero,” says Peter Alexander of Z-Ben Advisors, a Shanghai-based consultancy. Looked at narrowly, the index inclusions might seem technicalities. They are simply judgments about the accessibility of Chinese shares and bonds, not their value or prospects. And with minimal weights assigned to China, the inclusions are symbolic. But symbols can be powerful, as these certainly are. Some of the leading gatekeepers of global markets think China is at last open for business.

WHAT CAN CHINA AND THE U.S. LEARN FROM EACH OTHER ABOUT RETAIL?

George Hongchoy is the CEO of Link Asset Management Limited, which includes the Hong Kong listed Link Real Estate Investment Trust — the first REIT in Hong Kong and the largest in Asia.

The experience of his company acquiring a large number of retail properties from the government, then upgrading them, gives him a unique view of how the retail sector in Hong Kong and China is evolving. In this Knowledge@Wharton interview, he offers his views on online-to-offline retail, the differences between the retail sectors of China, Hong Kong and the U.S., and what lies ahead.

Hongchoy is also chairman of the supervisory committee of the Tracker Fund of Hong Kong, an exchange traded fund that follows the performance of the Hang Seng Index. He was named Business Person of the Year in Hong Kong as part of the DHL/SCMP Hong Kong Business Awards in 2015, and he received the Asian Corporate Director Award from Corporate Governance Asia. He was also named the Best CEO by FinanceAsia’s poll of Asia’s best companies in 2012-2015.

An edited transcript of the conversation follows.

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON: PLEASE TELL US ABOUT YOUR COMPANY.

Mr. George Hongchoy joined Link Asset Management Limited in January 2009 as the Chief Financial Officer. He became the Chief Executive Officer in May 2010. Link Asset Management Limited is the manager of Hong Kong listed Link Real Estate Investment Trust. He is the Chairman of the Supervisory Committee of the Tracker Fund of Hong Kong. He is a member of the Policy Research Committee of the Financial Services Development Council of the HKSAR Government, a member of the Council of The Hong Kong Institute of Directors and a member of the Asia Executive Board of The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Mr. Hongchoy was presented with Asian Corporate Director Award by Corporate Governance Asia from 2013 to 2015, Director of the Year Award under the category of Listed Companies — Executive Directors by the Hong Kong Institute of Directors and Outstanding Entrepreneurship Award by Enterprise Asia in 2011. He was also named “Best CEO” by FinanceAsia’s poll of Asia’s Best Companies from 2012 to 2015, and “Asia’s Best CEO (Property)” in Institutional Investor’s 2015 All-Asia Executive Team ranking. Mr. Hongchoy holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Canterbury and an MBA degree from The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. He is a Chartered Accountant with the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants, a Senior Fellow of HongKong Securities and Investment Institute, and a Fellow member of the Hong Kong Institute of Public Accountants, The Hong Kong Institute of Directors, the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and Institute of Shopping Centre Management and a Professor of Practice (Real Estate) at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

George Hongchoy: The Link Real Estate Investment Trust — or Link REIT, as we refer to it — was listed in 2005. It was the first real estate investment trust in Hong Kong. It acquired a portfolio of community shopping centers from the Hong Kong government. The government had been building these shopping centers as part of low-cost housing real estate, and the properties were put into the REIT…. We have since been transforming these assets, improving the retail space.

Over time we have also expanded beyond Hong Kong to China, with assets now in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. We have also expanded into new property types. Beyond the retail properties we also have offices, office buildings and car parks. The market cap of Link REIT is now roughly $18 billion.

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON: HOW DO REITS IN HONG KONG DIFFER FROM THOSE IN U.S.?

Hongchoy: To a large extent, how [REITs are] operated is very similar. The income, at least 90% of the income, needs to be distributed. We do not have the tax advantages of REITs in the U.S. … [which is] the only major difference, but by and large the main features are similar with gearing limits and with the minimum payout. The history obviously is that the REIT market really started in the U.S. in the 1960s and there are now over 1,000 REITs in the U.S. In Hong Kong there are only about a dozen, so it is a new market; it’s a new investment vehicle. But we have a lot of interest from investors all around the world and also retail investors in Hong Kong.

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON: We know that in the U.S., bricks-and-mortar stores are suffering — not only the stores but whole chains have been going out of business at a pace we haven’t seen for years, even as the U.S. economy seems to be improving. One result: A lot of malls have vacancies, a lot of malls are closing, or they are trying to repurpose their space and put in health clubs, office space and other uses. The culprits usually cited are the fact that there are too many stores in the U.S. and so there is a shakeout underway. The other big cause cited is competition from online sales, notably Amazon, often through the use of mobile. How does the retail experience for brick-and-mortar properties in Hong Kong and China differ from the U.S.?

Hongchoy: The history of the development of consumer sectors overseas is very different, yet we have seen a somewhat similar sort of trend growth of online retail. But the experience of having only started building shopping centers in the last 10 to 15 years means that there are not a lot of properties that were here 20 or 30 years ago, which don’t fit a current purpose as in the U.S., where some of them really have to change the layouts, and the type of services and products they are offering in the mall.

The Chinese consumer market has been growing rapidly, although it has seen some slowdown, but it still far exceeds the global average growth. We’ve seen double-digit growth in the early parts of 2010-2014. More recently, in 2016, it was still growing by 7%. So we have very strong growth in consumer spending, and the government policy is also shifting towards the consumer-driven rather than export-driven, which has helped consumer growth. And, wage levels have increased quite a lot in the last 10 years.

Online has indeed grown very fast. It now accounts for 13.5% of total retail sales compared to only 7.7% in the U.S. [A big part of the reason for that] is ownership of smartphones, especially in the last few years – there are very well-developed mobile payment solutions, and very easy and inexpensive delivery services. A lot of Chinese shoppers like to compare prices, and so online allows them to do that more easily than walking from shop to shop.

A combination of these factors has helped. I know [Wharton] professor David Bell has written a lot about what sort of products should be online or offline. We also are seeing, similar to other countries, that the online companies are also moving to have an offline presence and building a physical presence, or investing in physical retail chains. Over time it’s really a merger of the two experiences, to serve the consumers wherever they want to shop.

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON: In the U.S., you’ve got Bonobos and Warby Parker, and now Amazon has some physical stores. They are working to create a more seamless experience between the physical store and the online experience. What do you see in Hong Kong and China that relates to this approach? Are there lessons for the West?

Hongchoy: We have to realize firstly that a lot of people in China have never owned a PC, have never had a fixed line. So when mobile comes along, that’s the first thing that they have. What happened to drive the whole change is that the barrier to entry is a lot easier when you’re thinking about only building a business on mobile. So, skipping that technology legacy has helped China and a lot of the businesses to grow a lot faster.

And in the consumer mindset — every shopper is really just thinking about, “Okay, I want to buy something. How fast can I do that? What is my journey?” And during that journey, whether it is through the app or through the experience, they can actually gain some pleasure out of it. So there’s a lot of talk about that experience-based business model rather than the transactional — how we can actually make this fun for people. Even buying weekly groceries, why should that be a chore? Can’t it be fun?

Those are some of the things that I think a lot of businesses in China have been trying to come up with — new models for doing it. And maybe this is a part of globalization, but a lot of U.S. companies are trying to learn how China is doing it, and a lot of Chinese companies are going to the U.S. to learn.

I think there are a few advantages, though, in China. One is the payment solution. Most of the consumers in China either use Alipay or WeChat Pay. And having only one or two, or very few payment solutions will help the shoppers because they don’t have to open their wallet and choose from 10 different ones, and think “which one should I use this time?” On the flipside, merchants also do not have to install that many options — they wouldn’t know which shopper uses which [payment method] and so they would have to install ten different machines on the countertop [if there were many payment solutions].

So, having fewer payment solutions [helps]. I see that in the U.S., Amazon and eBay don’t really have a payment system well-embedded in their own platforms — relying on, I guess, other payment platforms. That is one issue. The other is this incumbent problem. If some of the retailers already have “X” number of stores, the incentive to move towards online becomes more difficult because every time the decision is, first, about how to strengthen the current physical presence. It makes the decision a lot more challenging. But if you don’t do it, I guess someone else will be eating your pie — you have to react.

The other thing I have noticed is that the consumer does want to go online to do a lot of research, but at the end of the day they want that physical touch and feel in the store, and so that cannot be replaced. In the end, I think one thing that is important is the social aspect of being with other people — whether it’s family, friends or classmates — in a physical location.

That is something that [will continue]. But it has to be fun.

So how can you make it easy [for consumers]? Make sure they know how to find what they want — whether there’s a parking app to find their car or an e-directory. And [retailers need] the sort of data analytics to understand the type of customer coming into the mall. There is a lot of research being done on both sides, both in the U.S. and Asia. And I think retailers are less worried than five years ago when everybody was sort of scared that it could be the end of physical retail. Now I think people have understood it more, and O2O [online to offline] has become the buzz word these days.

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON: In Hong Kong, e-commerce and mobile shopping haven’t caught on as much as in China, partly because of Hong Kong’s unique geography. It’s compact; it’s easy to get around. Can you talk about that difference, and also, I’m wondering if what you see in Hong Kong would also apply to places in the U.S. like New York City, for example? That’s also island.

Hongchoy: In Hong Kong or any compact city with high density, a good transport network does help because then it’s easy to get to the shops. And shop hours: Hong Kong shopping centers and shops tend to remain open very late into the night hours. Some people work until very late; in a lot of cities you can’t find anywhere to pick up your food [when it’s late], and there are other things that you want, but in Hong Kong the hours that shops remain open helps.

And then we have very small apartments [in Hong Kong]. When you have small apartments, the consequence is that it is very hard to entertain your friends and relatives at home. Shopping centers provide a place [and become] a much bigger part of your social life – it is not just for shopping but also for dining and entertaining. So, it’s not too different in New York – there are a lot of restaurants, and they do very well.

And [another] trend seems to be the case in a lot of places in the last couple of years where people have moved away from this heavy consumerism. How many shirts and pairs of trousers can you buy?

The past recession also made people [conscious of owning so much], and so now there is not a revolution — but certainly people are saying, “We actually want the experience; we actually want the entertainment, the gathering of people” and all that. In a compact city, that’s even more so than in a more spread out country.

In Hong Kong, the number of people shopping online has still gone up a lot — from 7% in 2004 to about 23% in 2014. The number is still behind China, but it is indeed rising, and people are trying it. And I think that is certainly the experience for any similar city, whether it’s New York or London.

HOW VACATIONS AFFECT YOUR HAPPINESS

By : Tara Parker-Pope .

CHRISTIE JOHNSTON FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES DO VACATIONS MAKE YOU HAPPY?

Vacations are a chance to take a break from work, see the world and enjoy time with family.

But do they make you happier?

Researchers from the Netherlands set out to measure the effect that vacations have on overall happiness and how long it lasts. They studied happiness levels among 1,530 Dutch adults, 974 of whom took a vacation during the 32-week study period.

The study, published in the journal Applied Research in Quality of Life, showed that the largest boost in happiness comes from the simple act of planning a vacation. In the study, the effect of vacation anticipation boosted happiness for eight weeks.

After the vacation, happiness quickly dropped back to baseline levels for most people. How much stress or relaxation a traveler experienced on the trip appeared to influence post-vacation happiness. There was no post-trip happiness benefit for travelers who said the vacation was “neutral” or stressful.”

Surprisingly, even those travelers who described the trip as “relaxing” showed no additional jump in happiness after the trip. “They were no happier than people who had not been on holiday,” said the lead author, Jeroen Nawijn, tourism research lecturer at Breda University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands.

The only vacationers who experienced an increase in happiness after the trip were those who reported feeling “very relaxed” on their vacation. Among those people, the vacation happiness effect lasted for just two weeks after the trip before returning to baseline levels.

“Vacations do make people happy,” Mr. Nawijn said. “But we found people who are anticipating holiday trips show signs of increased happiness, and afterward there is hardly an effect.”

One reason vacations don’t boost happiness after the trip may have to do with the stress of returning to work. And for some travelers, the holiday itself was stressful.

“In comments from people, the thing they mentioned most referred to disagreements with a travel partner or being ill,” Mr. Nawijn said.

The research controlled for differences among the vacationers and those who hadn’t taken a trip, including income level, stress and education. However, Mr. Nawijn noted that questions remain about whether the time of year, type of trip and other factors may influence post-vacation happiness.

The study didn’t find any relationship between the length of the vacation and overall happiness. Since most of the happiness boost comes from planning and anticipating a vacation, the study suggests that people may get more out of several small trips a year than one big vacation, Mr. Nawijn said.

“The practical lesson for an individual is that you derive most of your happiness from anticipating the holiday trip,” he said. “What you can do is try to increase that by taking more trips per year. If you have a two week holiday you can split it up and have two one week holidays. You could try to increase the anticipation effect by talking about it more and maybe discussing it online.”

Mr. Nawijn said that while he expected the study results to show a prevacation happiness boost, he was surprised that the study showed that relaxed holidays didn’t affect post-trip happiness levels.

“People start working again,” he said. “They have to catch up. Usually there is a big pile of work for them when they get back from the holiday.”

REINVENTING THE FRENCH PEOPLE

By : Bernard-Henri Lévy