ARTICULOS DE ORDEN INTERNACIONAL

SUBPRIME; HEDGE FUNDS Y US STOCKS

Por:Dennis Falvy

THE EVERYTHING BUBBLE, PART 1: RETURN OF THE SUBPRIME MORTGAGE

By : John Rubino (Dollar Collapse)

LONG-TERM HORIZON, CURRENCIES, GOLD, PORTFOLIO STRATEGY DOLLAR COLLAPSE

This cycle’s main bubble is in government bonds and fiat currencies, with a dash of large-cap tech thrown in for variety. But like a hurricane spawning tornadoes at its periphery, this Money Bubble is creating secondary bubbles like student debt and subprime auto loans that are impressively destructive in their own right.

An example of how extreme things have gotten is US housing, which — as the previous decade’s main bubble — wasn’t supposed to be a problem this time around. But apparently no sector is immune from all that excess central bank liquidity. As today’s Wall Street Journal notes, the subprime mortgage is now being resurrected:

DOES ANYONE REMEMBER HOW TO MAKE A SUBPRIME MORTGAGE?

Brokers willing to learn the lost art of making risky mortgages are in demand again

Brandon Boyd was a high school junior during the financial crisis. Now, the former Calvin Klein salesman is teaching mortgage brokers how to make subprime loans.

Mr. Boyd, a 25-year-old account executive at FundLoans in a beach town outside of San Diego, is at the cusp of efforts to bring back an army of salespeople who once powered the mortgage industry and, some say, contributed to the housing crisis.

Mortgage brokers, who serve as middlemen between lenders and borrowers, used to be a key part of the home-loan process. But some brokers faked loan applications and steered people into debt they couldn’t afford.

Financial regulation has severely diminished their ranks since the housing meltdown. And big banks with national sales teams say they won’t use brokers anymore because they are third-party contractors, making it harder to police loan quality.

Now, small and midsize independent lenders want the brokers back. Nonbank lenders that typically cater to riskier borrowers say they need brokers to fan out across the country and arrange mortgages to people with lower credit scores, or who can’t prove their income through a typical tax return.

Brokers are a key part of a mortgage chain that starts with a borrower going to a broker for a loan. The broker surveys lenders for the best loan to fit the customer. The lender then funds the borrower’s loan.

While brokers before the crisis served banks and independent lenders, today they are working largely for nonbank lenders who make up a critical part of the mortgage market.

In the first quarter, nonbank lenders accounted for about half the mortgages originated in the U.S., according to industry publication Inside Mortgage Finance.

Lenders say there is an untapped market among borrowers with good credit scores like self-employed workers who don’t have proper income documentation, or for responsibly made loans to borrowers with credit problems that have had bankruptcies in the past or had to sell their home for less than it was worth.

If they are successful in recruiting brokers, lenders believe the market potential for both types of loans could reach $200 billion annually.

Housing is late to the credit bubble party because the memory of its 2008 bust is still fairly fresh. So the lure of easy money had to become extremely powerful – and the fear of regulatory reprisal sufficiently weak – for subprime to once again be considered a serious business model.

APPARENTLY THAT DAY HAS ARRIVED.

Long expansions breed this kind of behavior because after five or six years of growth banks find that they’ve used up all their legitimate customers and must – if they want to maintain the deal flow on which their executives’ compensation is based – start scraping the bottom of the barrel. So they replace tried-and-true practices with “innovations” that are actually Ponzi schemes or other cons.

THEN THEY IMPLODE.

The question with housing is whether it has time to travel this road before the Money Bubble bursts, making the secondary bubbles irrelevant.

COST OF ‘BLACK SWAN’ BET ON FALLING MARKETS HITS PRE-CRISIS LOW

Hedge funds could make 25 times their money if S&P 500 falls 7 per cent in a month

BY: MILES JOHNSON IN LONDON .

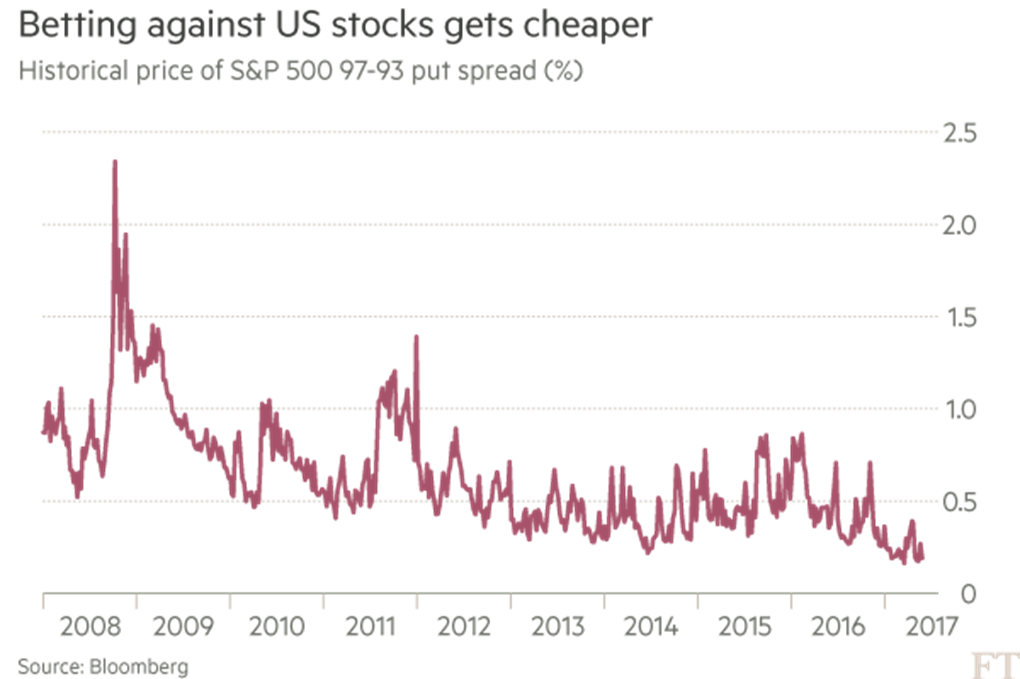

The cost for hedge funds of taking out “Black Swan” insurance against a sharp fall for US equities has fallen to the lowest level since before the financial crisis as stock markets continue to touch all-time highs.

Months of low market volatility has forced down the price of options allowing hedge funds to place bets that would make them 25 times on their money if the S&P 500 index fell by 7 per cent over the next month.

“The price of constructing hedges against a fall in equity markets are at their lowest levels ever, while equity markets are trading at all-time highs,” said Deepak Gulati, chief investment officer of Argentiere Capital and former head of equity proprietary trading at JPMorgan Chase.

“Historically low levels of volatility in options markets are providing the opportunity to construct long volatility positions with completely asymmetric pay-offs.”

At a time when equity markets continue to grind higher and most investors are betting that volatility will remain low, the potential for big payouts worth many multiples of their cost is tempting a small number of hedge funds to take the other side of that trade.

Options using the so-called one month 97-93 per cent put spread on the S&P 500, which requires the index to fall by between 3 and 7 per cent in a month to be profitable, currently allows a maximum profit of $4 for contracts that cost $0.16, or a 25 times return, according to Bloomberg data.

Expectations of market volatility, which make up an important input into how much options bets cost, have been plumbing new lows this year. Earlier this month, the Vix index, which tracks the implied volatility of the S&P 500 over the next 30 days, closed at the lowest level since 1993.

Last month the Financial Times reported that Ruffer, a $20bn London investment company, had been buying up large amounts of contracts linked to the Vix index priced at half a dollar as part of a hedging strategy for its portfolio, earning it the moniker “50 Cent” among bemused traders.

At the same time, low expected volatility also allows traders to make cheap bets using options on the US stock market also rising in value.

The so-called 3 month 105-110 per cent call spread on the S&P 500, which needs the index to rise by 5 to 10 per cent over three months to be profitable, would generate a profit of up to 38.5 times. This compares to an average pay-off ratio for an identical call spread of 5.6 times over the past decade.

THE GLOBAL AGE OF COMPLEXITY

By : Andrew Sheng ; Xiao Geng