¿ HAY MEJOR MANERA DE ENFRENTAR EL FINAL?

CLINICAS; HOSPITALES: ESTADO DE COMA; EUTANASIA; MUERTE ASISTIDA ....

Por:Dennis Falvy

La edición impresa de la Revista The Economist, trae hoy este artículo de un tema controversial , que yo reproduzco el mismo en su idioma original, ya que nos trae a colación el tema de la esperanza de vida que se alarga y los pormenores de lo que esto representa, hoy en día que los esquemas previsionales enfrentan los graves problemas de rentabilidad por una serie de motivos y que muchos de los que se benefician de ellos( el sistema de AFP´s ; las aseguradoras, el gobierno, ) tratan de convencernos que son sumamente rentables, lo que se choca con la cruda realidad de las pensiones de reemplazo cuya deterioro monetario es cada vez mayor, cualquiera sea el régimen de jubilación por el que uno opte, cuando más se alargue la vida.

Esto, sin tomar en consideración los gastos de medicinas y de salud en general, los que asimismo son “ probabilísticamente” mayores a medida que se vive más.

Ya hace un lapso prudencial, nosotros habíamos publicado en este blog, cómo el FMI y la actual jefa de este instituto, Christine Lagarde estaba preocupada por esta variable del alargamiento de la vida humana , pues ello afectaba las finanzas previsionales, así como un ministro de finanzas japonés que le parecía absurdo el alargamiento de la vida a sus connacionales en coma mediante máquinas de sobrevivencia , pues en su gran mayoría jamás despertaban del mismo y eran gastos onerosos para su gobierno.

Este aspecto que es real y que le hace al sistema previsional, no es de manera alguna tratada en países como el nuestro, que por un lado advierten que debe haber pensiones solidarias,de reparto o del sistema de AFP´s incluso juntándolos con los de la ONP; amén de rentabilidades financieras y supuestos soportes de salud, pero sin contemplar las advertencias que este interesante artículo de The Economist , nos advierte, al igual que la polémica que trae la eutanasia y la denominada muerte asistida, entre otras variables reales que deben enfrentar todos los seres humanos. Este es un post tal vez chocante para algunos, pero necesario de evaluarlo en sus “ perspectivas correspondientes” .

EUTANASIA Y MUERTE ASISTIDA

Encuentro en el Internet, un artículo de finales del año 2,015, que señala cómo con su firma, el gobernador de California, Jerry Brown acababa de convertir al estado en el quinto en el país en avalar legalmente el derecho que tiene un paciente terminal a elegir el momento de su muerte.

¿QUÉ ES LA MUERTE ASISTIDA?

Y, en qué se diferencia de otro controversial método para ayudar a morir: la eutanasia.

El lunes 5 de octubre de 2015, California se convirtió en el quinto estado en promulgar una ley que permite la muerte asistida o suicidio asistido. Antes lo hicieron Oregon, Vermont, Montana y Washington.

Ahora, por ley, un paciente que padece una enfermedad terminal y desea morir deberá contar con el aval de dos médicos que confirmen que, por el diagnóstico médico, a esa persona le quedan seis meses, o menos, de vida. El paciente debe tener la capacidad de tomar medicación por sí mismo y debe ser mentalmente capaz de tomar decisiones médicas.

Es importante aclarar que lo que hará este paciente que desea ponerle fin a su vida no es lo mismo que la eutanasia, aunque tiene el mismo objetivo: la muerte.

¿CUÁL ES LA DIFERENCIA?

• En la muerte asistida, el médico provee al paciente de la información y medicación necesaria para que el mismo paciente se quite la vida. El paciente debe tomar la medicación por sí mismo.

En la eutanasia, es el propio médico el que inyecta la dosis letal que acabará con la vida del paciente.

El derecho a morir con dignidad forma parte de la terapéutica en el final de la vida. Lo que sí está aceptado legalmente es que los médicos realicen cuidados paliativos, es decir que le den al paciente terminal medicinas que alivien su dolor y que disminuyan casi al mínimo su sufrimiento final, según explica un trabajo del Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center de la Universidad Northwestern.

La Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos considera a los cuidados paliativos un derecho del paciente, pero a principios de los 90 dejó librado a los estados la decisión de aprobar o no leyes sobre la muerte digna.

En el país, Oregon fue pionero porque fue el primer estado en votar la ley en 1997. En el mundo, sólo Bélgica, Suiza y Holanda han promulgado leyes claras y abiertas sobre la muerte asistida.

El caso que cobró mayor popularidad recientemente fue el de la joven Brittany Maynard, quien antes de tener una muerte asistida en Oregon el Día de los Muertos, el 2 de noviembre de 2014, realizó una cruzada nacional en defensa de este método y del derecho del paciente a elegir cómo y cuándo morir.

La muerte asistida por un médico (Physician-Assisted Suicide o PAS, en inglés) —también llamada muerte digna— es, para muchos, un acto de piedad, a pedido de un paciente al que le queda poco tiempo de vida, o un tiempo de vida con un deterioro físico y mental muy grandes. Las principales razones por las cuales los pacientes terminales piden morir son: una enfermedad dolorosa, la futura pérdida de las facultades mentales, la indignidad de verse postrados y no querer ser una carga para otros.

El mismo trabajo de la Universidad Northwestern explica que la espiritualidad ocupa un lugar muy grande en el final de la vida de muchos pacientes, quienes sienten que no están desafiando a Dios al querer quitarse la vida.

El Death with Dignity National Center, una organización sin fines de lucro con sede en Oregon que promueve la muerte asistida, explica que, antes de decidir la fecha de la muerte, los pacientes deben firmar una "decisión informada" que es distinta al "consentimiento informado" que se da por ejemplo para autorizar una cirugía.

El paciente debe firmar esta "decisión informada" luego de entrevistas con su médico, con otros especialistas, incluido un psiquiatra quien evalúa que la persona tiene sus facultades mentales plenas, para tomar esa decisión.

Actualmente la medicación que más se utiliza para el proceso de muerte digna es Secobarbital. Pentobarbital es la segunda opción. Se prescriben 9 miligramos que el farmacéutico prepara, recomendando tomar la medicina con un jugo por su sabor amargo. Es una única toma, con el estómago vacío para facilitar la absorción.

Los pacientes también deben tomar, una hora antes de la medicina letal, una medicina para prevenir vómitos y diarreas, que pueden anular el efecto del secobarbital.

Desde que se legalizó el suicidio asistido en Oregon, 460 personas han elegido el camino de la muerte digna. El 80 por ciento de estos pacientes padecían formas de cáncer agresivas e irreversibles. El 75 por ciento tenía entre 55 y 84 años.

Aún así, la muerte puede hacerse esperar, tras tomar la medicación pueden pasar de 2 minutos hasta cuatro días y medio para morir.

VIDA DESGASTADA O MUERTE DIGNA, POLÉMICO DEBATE SOBRE EUTANASIA

Por: teleSUR - El Mundo - Forum Libertad - AFP / sb

Países Bajos, Bélgica, Luxemburgo y algunos estados de Estados Unidos contemplan la muerte asistida. Las discusiones sobre esta práctica muestran detractores que defienden a población vulnerable como los ancianos, mientras que quienes la respaldan defienden el derecho de las personas a decidir sobre su vida.

Una propuesta de Ley de Muerte Asistida fue rechazada este viernes en la Cámara de los Comunes del Parlamento del Reino Unido, instancia legislativa donde la medida recibió 330 votos en contra.

Sin embargo, el hecho de que el proyecto recibiera 118 a favor, muestra que el tema genera tanta controversia en el país europeo como en otras naciones del orbe donde es objeto de debate

De haber sido aprobada, la ley facultaría a los médicos para prescribir una dosis letal a los pacientes con enfermedades terminales y una expectativa de seis meses o menos de vida.

El dato→ La palabra eutanasia viene del griego euthanasía que significa “buena muerte” y contempla la muerte asistida con consentimiento de los pacientes o sin consentimiento en caso de pacientes en coma.

Según la última encuesta sobre el tema, la mitad de la población británica se mostró a favor de la eutanasia, mientras que la otra lo rechazó.

Detractores recuerdan a los ancianos en riesgo.

Quienes se niegan a la aprobación de la ley ponen en medio de la discusión el asunto de sectores vulnerables como los ancianos. Un grupo de 80 médicos británicos hizo pública una carta en la que alertan sobre los riesgos de la aprobación de la eutanasia en ese conjunto etario, pues pueden ser presionados para que acepten su aplicación.

Los galenos manifiestan su preocupación debido a que reciben muchas personas que se consideran una carga para sus familias a causa de sus enfermedades y limitaciones, lo que podría influir en la decisión de solicitar el suicidio asistido.

"Este tipo de propuestas perjudican a los más vulnerables de nuestra sociedad", aseveran los doctores en la misiva.

El dato→ La población en Reino Unido muestra un gran envejecimiento motivado por el aumento en un 35% de la esperanza de vida y por un descenso continuado del 65% en la natalidad.

DEFENSORES: APOYAN UNA MUERTE DIGNA

Por el otro lado, hay quienes argumentan que la eutanasia es necesaria para aquellos que sufren enfermedades terminales y dolorosas. Así lo expresan otro grupo de 27 médicos británicos, que reclamaron públicamente a la aprobación de la ley que, a su juicio, “será un alivio para un número significativo de pacientes que sufren tremendamente en sus últimos días".

También el físico Stephen Hawking mostró su apoyo a esta opción y aseguró que no dudaría en acogerse a ella si sintiera que no tiene nada más que aportar a la sociedad o si los dolores causados por la esclerosis lateral amiotrófica que padece se hicieran insoportables.

La campaña Dignity of Dying reclamó este viernes a las puertas del Parlamento la aprobación de la ley, sobre todo después de que 35 ciudadanos británicos tuvieran que trasladarse a Suiza para poder recurrir a la muerte asistida de forma legal.

OTRAS EXPERIENCIAS LEGALES

La eutanasia está contemplada legalmente en naciones como los Países Bajos, Bélgica, Luxemburgo y algunos estados de Estados Unidos. De hecho, California sería el sexto territorio de la nación norteamericana en autorizarla, luego de que el Senado de esa nación aprobara este miércoles la ley.

En América Latina también hay referencias de estos suicidios asistidos y Colombia figura en este asunto como precursor, luego de que en 1997 despenalizara el “homicidio por piedad”.

Sin embargo, no fue hasta este año que se registró el primer caso en ese país, cuando Ovidio González, de 79 años y con una enfermedad terminal, pidió, en pleno uso de sus facultades mentales, que se le aplicara una eutanasia. Así se convirtió en el primer ciudadano colombiano en someterse a la muerte asistida.

Mientras tanto, en 2008 México aprobó una reforma de ley que establece que los enfermos terminales pueden solicitar de forma legal la eutanasia pasiva a su médico, lo que consiste en dejar de recibir los medicamentos o aparatos que los mantienen con vida. Aún la eutanasia activa en ese país está en debate.

En Argentina también se aprobó la ley de "muerte digna" en mayo de 2012 para que los pacientes con enfermedades terminales reciban la eutanasia pasiva.

La estadounidense Brittany Maynard padecía un tumor cerebral y ante la amenaza de una muerte dolorosa y lenta planificó su muerte. La joven de 29 años viajó desde San Francisco a Oregon, donde está legalizada la muerte asistida, y pautó para noviembre su muerte, pero antes cumplió una lista de cosas por hacer en su vida.

"Adiós a todos mis queridos amigos y familiares que me aman. Hoy es el día que he elegido para morir con dignidad en vista de mi enfermedad terminal, este tipo de cáncer cerebral terrible que ha tomado mucho de mí... pero que habría tomado mucho más", escribió en su cuenta de Facebook como mensaje de despedida.

Otra historia fue la de la chilena Valentina Maureira, quien en febrero de este año pidió a la presidenta de esa nación, Michelle Bachelet, permitir que se le aplicara la eutanasia por estar “cansada de vivir” con fibrosis quística.

Sin embargo, su petición fue rechazada por no estar contemplada en la legislación de ese país y la adolescente de 14 años murió de una insuficiencia respiratoria tres meses después. No obstante, la mandataria acudió en varias ocasiones a visitarla y garantizó que recibiera todo lo requerido para el tratamiento contra la enfermedad.

PROYECTO DE EUTANASIA COLECTIVA

Existe un proyecto conocido como Eutahanasian Coaster, que plantea una forma inusual de aplicar la eutanasia: se trata de una montaña rusa que fue diseñada y hecha a escala con la cual sus 24 tripulantes morirían al finalizar el recorrido a causa de una hipoxia cerebral, es decir, insuficiente oxígeno en el cerebro.

De esta manera, en 60 segundos las personas que entraron vivas experimentarían una visión gris, visión de túnel, entrarían a un estado de inconsciencia y saldrían muertas. Para personas más robustas la montaña rusa en su tramo final cuenta con unas serie de giros que sirven de seguro en caso de una superviviencia no intencional.

Esta polémica forma de eutanasia masiva, que fue presentado como un concepto artístico en 2010, seguramente arroja aún más leña al debate de un tema sobre el que las posiciones siguen divididas.

CRTICA A GEORGE SOROS

17 de junio de 2008 (LPAC).— En 1994, la rata asesina de Londres, George Soros, empezó un proyecto para ayudar a promover la idea de la eutanasia y la legalización del "suicidio asistido". En un ensayo titulado "Reflexiones sobre la Muerte en América" Soros se explaya, "¿Qué es lo que queremos transformar y por qué? Una explicación comienza con un asunto menor, el nombre de nuestro proyecto. Hubo grandes discusiones hasta deshacernos de los eufemísmos ingeniosos y estar de acuerdo en un nombre que estableciera directamente nuestro propósito, aunque fuera duro: El proyecto sobre la muerte en América". Después pasa a quejarse de que se le presta demasiada atención a prolongar la vida humana, afirmando que el "énfasis en tratar las enfermedades, en vez de aportar cuidados ha alterado la práctica de la medicina. La gente vive más y sufren cuatro o cinco enfermedades antes de morir. Pero la cuenta por el cuidado de la salud crece con cada enfermedad...los doctores y enfermeras trabajan para prolongar la vida, en vez de preparar al paciente para la muerte". Soros decide que la forma de solucionar el supuesto problema que tienen los doctores en "prolongar la vida" se puede resolver entrenando a los doctores y enfermeras en el "cuidado a los agonizantes". En la parte final de su ensayo, Soros llega hasta decir que " incluso aunque se legalizara el suicidio asistido muy pocos enfermos moribundos aprovecharían esto. Después de todo, mi madre negó mi ayuda y estoy contento de que lo haya hecho". Soros se jacta, en cada ocasión que puede, incluyendo el prefacio a la edición del 2000 de las memorias de su padre, que lo que ha definido toda su vida fue su experiencia cuando era jovencito en una Hungría ocupada por los nazis, cuando se hizo pasar por el "ahijado" de un funcionario medio del ministerio de agricultura, y ayudó a confiscar propiedades de los judios -mientras se "eliminaba" a la mitad de la población judia de ese pais. Soros dice que no siente remordimientos o culpa por el exterminio de judios húngaros. La idea que tiene Soros de la santidad de la vida humana, es la de un sociópata.

STEPHEN HAWKING: "NO PERMITIR LA MUERTE ASISTIDA ES DISCRIMINATORIO"

El 18 de julio del año 2,014 Fergus WalshCorresponsal de Salud, BBC

Derechos de autor de la imagen GETTY caption. El científico británico Stephen Hawking considera que todo el mundo debería tener derecho a acabar con su vida.

El científico de la Universidad de Cambridge, Reino Unido, Stephen Hawking defendió la muerte asistida en declaraciones a la BBC este jueves, la víspera de que la Cámara de los Lores del parlamento británico debata un proyecto de ley sobre la cuestión.

"No permitimos que los animales sufran. Entonces, ¿por qué debería tu dolor prolongarse más allá de tus deseos?". El cosmólogo de 72 años, completamente paralizado a causa de una enfermedad, considera que no permitir el procedimiento es "discriminatorio", ya que supone "negar a las personas con discapacidad el derecho a quitarse la vida que sí tienen aquellas sin discapacidades".

"Creo que todos deberían tener el derecho a acabar con su vida, tanto si son capaces de hacerlo sin asistencia como si no", añadió.

Intenté una vez suicidarme, aguantando el aliento. Pero el acto reflejo de respirar fue demasiado fuerteStephen Hawking, científico británico.

Hawking padece una afección motoneuronal relacionada con la esclerosis lateral amiotrófica (ELA) desde hace medio siglo. Su estado se ha ido agravando con el paso de los años, hasta quedarse casi completamente inmovilizado, y forzado a comunicarse a través de un aparato generador de voz.

LIBERTAD PARA ELEGIR MORIR

"Dicho esto, creo que sería un error desesperarse y cometer suicidio, a no ser que se sufra un gran dolor. Pero es una cuestión de elección", dijo. "No deberíamos quitar al individuo la libertad de elegir morir".

Ante esto, el también físico teórico y divulgador británico subrayó que es necesario garantizar que la persona realmente quiera morir.

Asimismo, Hawking admitió que en una ocasión trató de quitarse la vida. Le habían realizado una traqueotomía, una operación mediante la cual se abre la tráquea del paciente para permitirle a éste respirar de forma artificial.

El parlamentario Charles Falconer es el propulsor del proyecto de ley en Reino Unido.

"Intenté brevemente suicidarme, aguantando el aliento", contó. "Pero el acto reflejo de respirar fue demasiado fuerte".

El proyecto de ley, propuesto por el parlamentario Charles Falconer, del Partido Laborista, y que se debatirá este viernes en la cámara alta, propone permitir a los médicos prescribir una dosis letal a pacientes a los que se les haya diagnosticado menos de seis meses de vida.

Más de 130 parlamentarios han pedido permiso para hablar en el debate. Y el ministro de Asistencia Norman Lam, del Partido Liberal Demócrata ha declarado que apoyará el proyecto de ley.

END-OF-LIFE CARE

A BETTER WAY TO CARE FOR THE DYING

By: THE ECONOMIST

How the medical profession is starting to move beyond fighting death to easing it .

A STROLL from Todoroki station, at the kink of a path lined with cherry trees, lies a small wooden temple. A baby Buddha sits on the sill. The residents of the Tokyo suburb ask the infant for pin pin korori. It is a wish for two things. The first is a long, spry life. The second is a quick and painless death.

Just part of this wish is likely to be granted. The paradox of modern medicine is that people are living longer, and yet doing so with more disease. Death is rarely either quick or painless. Often it is traumatic. As the end nears, people tend to have goals that matter more than eking out every last second. But too few are asked what matters most to them. In the rich world most people die in a hospital or nursing home, often after pointless, aggressive treatment. Many die alone, confused and in pain.

The distress is largely unnecessary. Fortunately medicine is beginning to take a more thoughtful approach to people with terminal illness. Reformers are overhauling how end-of-life care is delivered and improving communication between doctors and patients. The changes mean that patients will experience less pain and suffering. And they will have more control over their lives, right up until the end.

Many aspects of death changed during the 20th century. One was when it happens. The average lifespan increased by more over the past four generations than over the previous 8,000. In 1900 global life expectancy at birth was about 32 years, little more than at the dawn of agriculture. It is now 71.8 years. In large part that is a result of lower infant and child mortality; a century ago about a third of children died before their fifth birthday. But it is also because adults live longer. Today a 50-year-old Englishman can expect to live for another 33 years, 13 more than in 1900.

The chance of an adult dying was once largely unrelated to age; infections were indiscriminate. Michel de Montaigne, a French essayist who died in 1592, wrote that death in old age was “rare, singular and extraordinary”. Now, says Katherine Sleeman of King’s College London, death mostly comes by stealth. She estimates that in Britain only a fifth of deaths are sudden, for example in a car crash. Another fifth follow a swift decline, as with some cancer patients, who stay fairly active until their final few weeks. But three-fifths come after years of relapse and recovery. They involve a “slow, progressive deterioration of function”, Dr Sleeman says.

People in rich countries can spend eight to ten years seriously ill at the end of life. Chronic illness is rising in poorer countries, too. In 2015 it accounted for more than three-quarters of premature mortality in China, according to the Global Burden of Disease, a survey. In 1990 the share was just a half. The World Health Organisation (WHO) predicts that rates of cancer and heart disease in Sub-Saharan Africa will more than double by 2030.

A side-effect of progress, however, has been what Atul Gawande, a surgeon and author, calls “the experiment of making mortality a medical experience”. A century ago most deaths were at home. Now, according to a survey of 45 rich countries by the WHO, fewer than a third are. Death also used to be egalitarian, says Haider Warraich of Duke University Medical Centre and the author of “Modern Death”. Income did not much affect when or where people died. Today poor people in rich countries are more likely than their better-off compatriots to die in hospital.

NO DYING FALL

Many deaths are preceded by a surge of treatment, often pointless. A survey of doctors in Japan found that 90% expected that patients with tubes inserted into their windpipes would never recover. Yet a fifth of patients who die in the country’s hospitals have been intubated. An eighth of Americans with terminal cancer receive chemotherapy in their final fortnight, despite it offering no benefit at such a late stage. Nearly a third of elderly Americans undergo surgery during their final year; 8% do so in their last week.

The way health care is funded encourages over-treatment. Hospitals are paid for doing things to people, not for preventing pain. And not only patients, but those who love them, suffer. Many people who may need intubation or artificial ventilation are not in a condition to indicate consent. An American study found that in about half of cases involving decisions about the withdrawal of treatment there is conflict between family and doctors. A third of relatives of patients in intensive-care units (ICUs) report symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Many people will want to “rage, rage against the dying of the light”, as the poet Dylan Thomas put it.

Others will have particular events they want to attend: a grandchild’s graduation, say. But the medical crescendo often occurs by default, not as a result of personal choice based on a clearly understood prognosis.

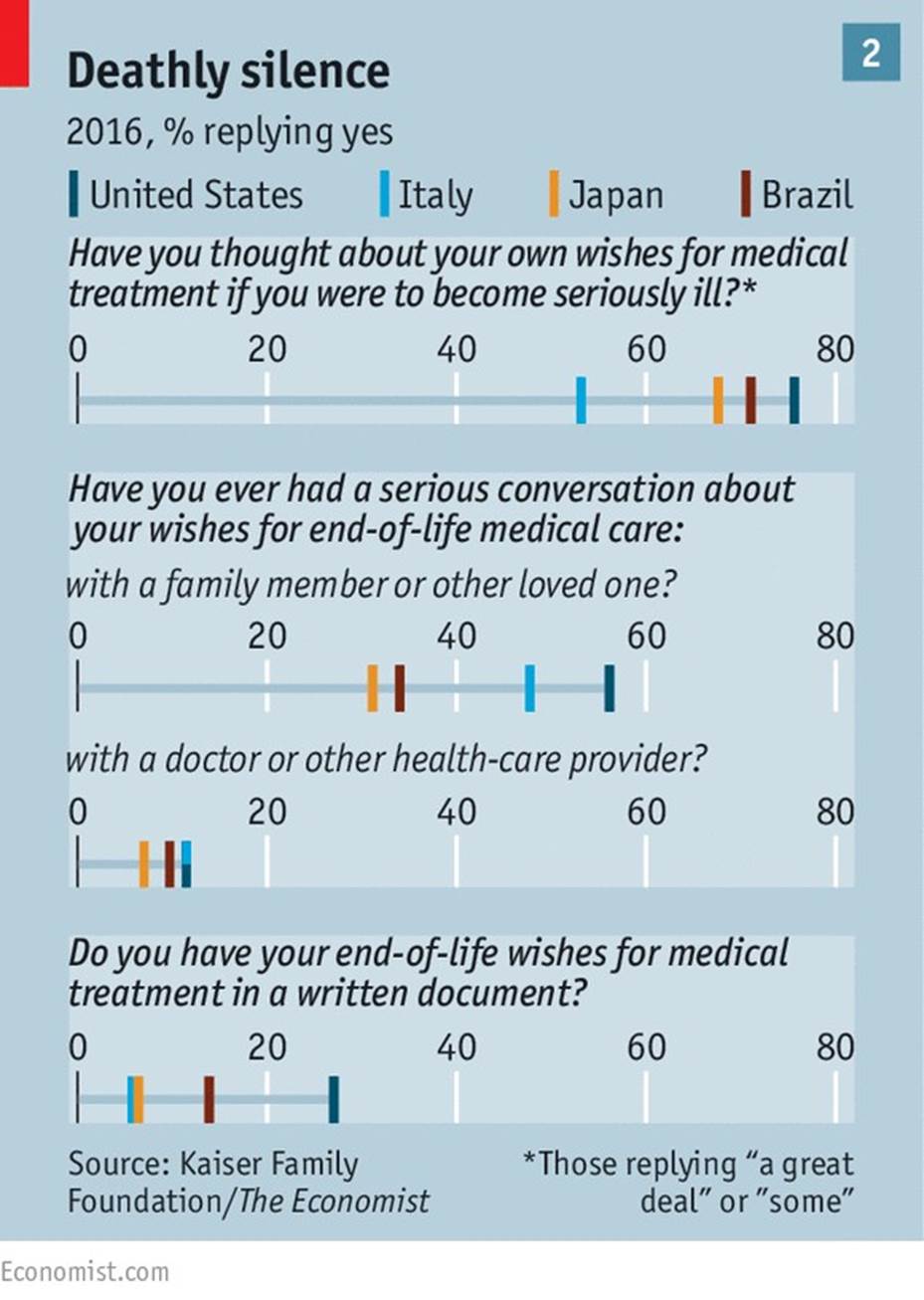

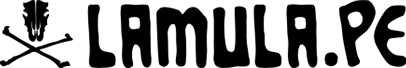

The huge gap between what people want from end-of-life care and what they are likely to get is visible in a survey conducted by The Economist in partnership with the Kaiser Family Foundation, an American health-care think-tank. Representative samples of people in four large countries with differing demographics, religious traditions and levels of development (America, Brazil, Italy and Japan) were asked a set of questions about dying and end-of-life care. Most had lost close friends or family in the previous five years.

In all four countries the majority of people said they hoped to die at home (see chart 1). But fewer said they expected to do so—and even fewer said that their deceased loved ones had.

Apart from in Brazil, only small shares said that extending life as long as possible was more important than dying without pain, discomfort and stress. Other research suggests that wish, too, is increasingly unlikely to be granted. One study found that between 1998 and 2010 the shares of Americans experiencing confusion, depression and pain in their final year all increased.

What healthy people think they will want when they are mortally ill may well change when that moment comes. “Life becomes mighty precious when there is not a lot left,” says Diane Meier, a geriatrician at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. It is common, for example, to hate the idea of a feeding tube but grudgingly accept one when the alternative is death.

WORDS I NEVER THOUGHT TO SPEAK

Yet the gap between what people hope for and what they get cannot be explained away so easily.

Dying people’s wishes are often unknown or ignored. Among those involved in making decisions about a loved one’s end-of-life care, more than a third in Italy, Japan and Brazil said they did not know what their friend or family member wanted. Either they never asked, or only thought to do so too late. A Japanese woman who cared for her mother, an Alzheimer’s patient, says she regrets that “once the door closed there was no way of knowing what she wanted.”

And sometimes, even when relatives know a loved one’s wishes, they cannot make sure they are granted. Between 12% and 24% of those who had lost someone close to them said that the patient’s wishes had not been carried out. Between 25% and 38% said that friends or family had experienced needless pain. Across the whole survey most people rated the quality of end-of-life care as “fair” or “poor”.

End-of-life care can resemble a “conspiracy of silence”, says Robert Fine of Baylor Scott & White Health, a Texan health-care provider. In our survey majorities in all four countries said that death is a subject which is generally avoided. An obvious reason is that death is feared. “In every calm and reasonable person there is a hidden second person scared witless about death,” says the narrator of a Philip Roth novel. One school of psychology—“terror management theory”—holds that fear of death is the source of everything distinctively human, from phobias to religion.

But death was once what Philippe Ariès, a French historian, called a “public ceremony”, where friends and family gathered. Now, changing family structures mean the elderly and dying are more isolated from younger people, who are therefore less likely to witness death up close, or to find a suitable moment to talk about its approach. Just 10% of Europeans aged over 80 live with their families; half live alone. By 2020, 40% of Americans are expected to die alone in nursing homes.

In Japan, where survey respondents were most likely to say that not being a financial burden was a primary consideration, daughters are abandoning their traditional caring role. That has given rise to institutions such as the House of Hope, a hospice in east Tokyo that looks after people who are too poor for hospital care and too alone to die at home. A decade ago Hisako Yanagida, 88, lost her husband, with whom she had sung in a traditional Japanese troupe. Now her sight is going but she can still make out the faded pictures of the two of them on her wall. She tries not to think about death: “There is no point.”

But the chief responsibility for the failures of end-of-life care lies with medicine. The relationship between doctors and seriously ill patients is one of “mutual suspicion”, says Naoki Ikegami of St Luke’s International University, in Tokyo. A decade ago it was common for Japanese doctors to withhold cancer diagnoses. Today they are more honest, but still insensitive. One Japanese woman recalls her oncologist saying that if her chemotherapy made her bald, it would not be a big deal.

And doctors commonly overestimate how long the terminally ill will live, making it more likely that they will duck frank conversations, or recommend drastic treatments that have little chance of success. One international review of prognoses of patients who die within two months suggests that seriously ill people live on average little more than half as long as their doctors suggested they would.

Another study found that, for patients who died within four weeks of receiving a prognosis, doctors had predicted the date to within a week in just a quarter of cases. Mostly, they had erred on the side of optimism.

Doctors often neglect palliative care, which involves giving opioids for pain, treating breathlessness and counselling patients. (The name comes from the Latin palliare, as in “to cloak” pain.) A typical question is “What is important to you now?” It does not seek to cure. As a result, “it is seen as what you do when you give up on a patient,” sighs Dr Ikegami. It receives just 0.2% of the funding for cancer research in Britain and 1% in America.

BREAKING THE TABOO

What studies there have been show the cost of this neglect. Since 2009 several randomised controlled trials have looked at what happens when patients with advanced cancer are given palliative care alongside standard treatment, such as chemotherapy. In each, the group receiving palliative care had lower rates of depression; and in all but one study, patients in that group were less likely to report pain.

Remarkably, in three trials the patients receiving palliative care lived longer, even though the quantity of conventional treatment they opted to receive was lower. (The other two trials showed no difference.) In one study their median survival was a year, compared with nine months for the group receiving only ordinary treatment. A review in 2016 of cases where palliative care was used instead of standard treatment found that even when it was the only care given, it did not seem to shorten life.

The reason for the results is unclear, and the research has mostly been on cancer patients. Those receiving palliative care spend less time in hospital, so may contract fewer infections. But some researchers think that the explanation is psychological: that through counselling they reduce depression, which is linked to earlier death. “A conversation can be more powerful than technology,” says Dr Sleeman.

At St Luke’s hospital in Tokyo, Yuki Asano supports the argument. Ever the executive, the 76-year-old slides his business card across the tray of his bed. The former boss of a brewery company (and 7th dan in kendo, a Japanese martial art) is riddled with cancer. He stopped chemotherapy last year.

The care at one of Japan’s few dedicated palliative centres has helped him feel ready for death. “I achieved everything I wanted in life,” he says. “Now I am waiting for the awards ceremony.”

But few of the 56m or so people who die each year receive good end-of-life care. A report published in 2015 by the Economist Intelligence Unit, our sister company, assessed the “quality of death” in 80 countries. Only Austria and America, the EIU found, had the capacity to ensure that at least half the patients for whom palliative care was suitable received it.

Many countries promise public access to palliative care but do not pay for it. Spain has passed two laws to ensure palliative care is available but in reality, just a quarter of patients can get it.

Though the hospice movement, dedicated to providing high-quality care to dying patients, started in Britain in the 1960s, only about a fifth of the country’s hospitals provide access to palliative care every day of the week.

The way health-care providers are funded often sidelines palliative care. In Japan hospital doctors receive no payment from insurers for talking to patients about end-of-life options. In America hospitals suck up a big share of spending, even though the seriously ill are often better treated elsewhere. Nine in ten emergency visits are because of escalations in symptoms, such as breathlessness; most of these patients could be treated better, faster and more cheaply at home.

Medicare, the public-health scheme for the elderly, does not generally cover spells in nursing homes.

Slowly, however, countries are reforming. In 2014 the WHO recommended integrating palliative care with health systems. Some developing countries, including Ecuador, Mongolia and Sri Lanka, are beginning to do so. In America some insurers are realising that what would be better for patients would be better for them, too. In 2015 Medicare announced that it would pay for conversations about end-of-life care between doctors and patients.

“Talking almost always helps and yet we don’t talk,” says Susan Block of Harvard Medical School.

To improve end-of-life care, she says, “every doctor needs to be an expert in communicating.”

American oncologists, for example, need to have an average of 35 conversations per month about end-of-life care. In a study of patients with congestive heart failure, doctors rarely followed up after a patient expressed a fear of death. Nearly three-quarters of nephrologists were never taught how to tell patients they are dying. A common cause of burnout among doctors is an inability to talk with patients about death.

To fill this gap Ariadne Labs, a research group founded by Dr Gawande, has launched the “Serious Illness Conversation Guide”. It is a straightforward checklist of the topics doctors should be sure to talk about with their terminally ill patients. They should start by asking what patients understand about their conditions, check how much each wants to know, offer an honest prognosis, and ask about their goals and the trade-offs each is willing to make.

Early results from a trial of the guide at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston suggest it led to doctors having more and earlier conversations. Patients reported less anxiety. Tension between doctors and families was eased. The scheme is being expanded; in February Baylor Scott & White became the first big provider to use it for all its staff. England’s National Health Service is trying it out in Clatterbridge, near Liverpool. Japan is retraining its oncologists in how to talk about death.

In America advance directives and living wills, documents that spell out the treatment people want if they become incapacitated, have become more popular over the past few decades. In our survey 51% of Americans over 65 had written down their end-of-life wishes. Yet such documents cannot cover all the possibilities that may arise as the end nears. Doctors worry that patients may have changed their minds. In one study just 43% of people who had written living wills wanted the same treatment course two years later.