ANALITICOS POST : DE NIVEL INTERNACIONAL

BANQUEROS;DEFICIT; SAUDI ARABIA Y CAPITALES A LATINO AMERICA

Por:Dennis Falvy

BANKERS USE TRUMO RALLY TO CASH OUT

Executives, directors at nearly 100 community banks and regional players netted $1 billion in stock sales since election

BY : RACHEL LOUISE ENSIGNAND TOM MCGINTY

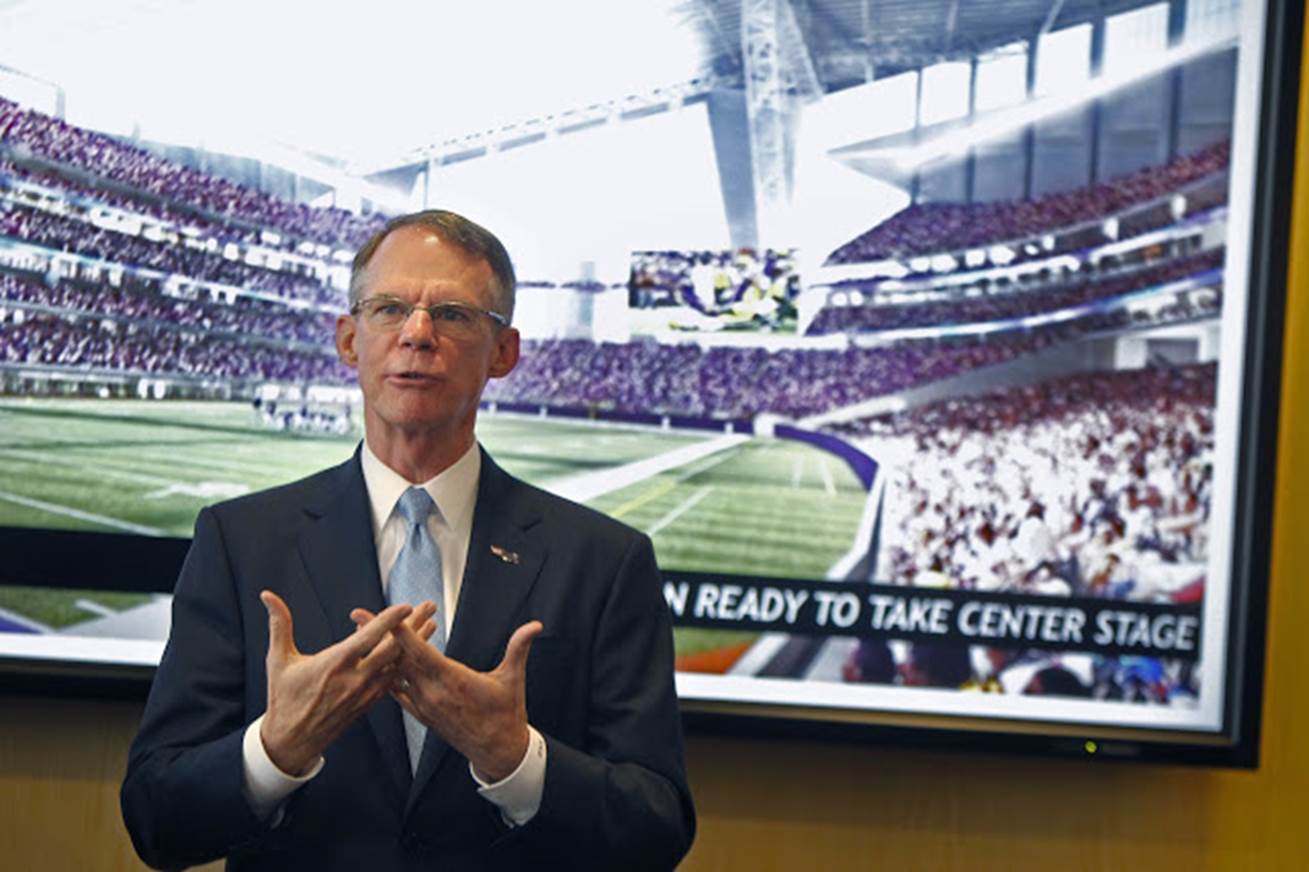

U.S. Bank CEO Richard Davis, who retired from that role earlier this month, sold $73 million of stock in November and January, netting $28 million after exercise costs. Photo: Elizabeth Flores/Associated Press

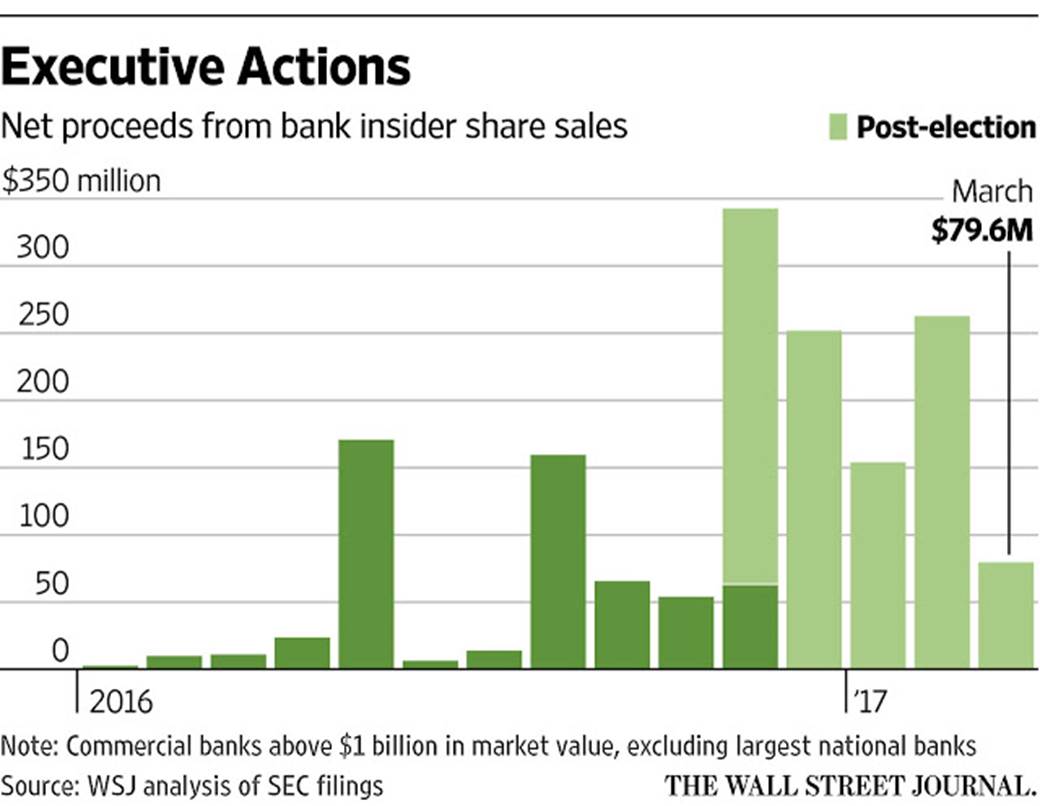

Investors rushed into regional and community bank stocks after the U.S. election, encouraged by higher interest rates and potential regulatory relief. Top executives and directors at banks used the rally for a different reason: to cash out.

Insiders at publicly traded commercial banks with a market value greater than $1 billion, but excluding the largest national banks, sold about $1.4 billion in their company stock between the election and the end of March, up 65% from the 10-plus months in 2016 before the election, according to an analysis by The Wall Street Journal.

The sales netted executives and directors at banks like PNC Financial Services Group Inc. PNC -0.80%▲ and U.S. Bancorp USB -0.38%▲ $1 billion when taking into account the cost of exercising options.

The moves are in line with the behavior of insiders at the biggest U.S. banks, which was the subject of a Wall Street Journal article in January.

Executives at some of the country’s largest banks sold about $163.5 million worth of stock since the presidential election, more than in that same period in any year since before the financial crisis, according to an updated Wall Street Journal review of securities filings.

At the nearly 100 community banks and regional players included in the Journal’s latest review, net gains from selling since the election totaled about $7.2 million per day—nearly four times the 2016 pace before the election.

For years, bank stocks lagged behind the broader stock-market rally as low interest rates and a regulatory overhang from the financial crisis weighed on results. Last year started with the KBW Nasdaq Bank index falling as much as 23% by mid-February due to recession fears. During that time, insiders did very little selling, netting just $13 million on share sales in the first two months of 2016.

After Donald Trump’s surprise election win, potential tax and regulatory relief from the new administration gave bank investors a rosier view. Interest rates also started to rise, which helps bank profits.

While bank stocks have flagged a bit in recent months, the KBW index still rose by more than 22% between the election and the end of March, the period of increased insider selling.

Alex Lieblong, a director at Arkansas-based Home BancShares Inc., netted about $25 million in sales of the bank’s stock after the election, compared with about $1 million before the election in 2016. The 66-year-old investor said his estate planners told him that he needed “a little diversification here in case you get hit by the proverbial bus.”

Bank insiders still have vast holdings in their companies. Executives often are given shares through stock or options grants as part of compensation. Sometimes, they purchase shares on the open market or through their retirement plans. In 2016 before the election, 255 insiders at these lenders bought $42 million worth of stock. After the election through the end of March, the purchases amounted to $5 million from 55 insiders.

Private-equity investors with board seats also sold. Four of them accounted for more than $310 million of the sales, or about 22% of the total, since the election. These same investors sold $46 million in 2016 before the election.

While it is relatively unusual for private-equity investors to have stakes in banks due to regulatory restrictions, some got involved during or shortly after the crisis.

Oaktree Capital Management LP and Thomas H. Lee Partners LP, for instance, in 2011 invested more than $350 million in Puerto Rico-based First BanCorp as a part of a capital raise. The two private-equity investors, which declined to comment, sold about $257 million worth of First BanCorp stock in December and February. The stock is up 62% in the last 12 months through Wednesday.

Another recent seller: U.S. Bank CEO Richard Davis, who retired from that role earlier this month. In November and January, he sold $73 million of stock, netting $28 million after exercise costs. The bank said the moves were an exercise of options from 2008 and declined to comment further on Mr. Davis’s behalf.

PNC CEO William Demchak, meanwhile, sold $40 million, netting $21 million.

Both Messrs. Demchak and Davis remain significant shareholders in their banks. The stocks have both hit record highs in 2017 after steadily recovering since the financial crisis.

Given “the rise in PNC’s stock price during this time frame, I viewed it as an opportune time to exercise” stock options that were set to expire in the next two years, Mr. Demchak noted.

INCOVENIENT TRUTHS ABOUT THE US TRADE DEFICIT

BY : MARTIN FELDSTEIN

CAMBRIDGE – The United States has a trade deficit of about $450 billion, or 2.5% of GDP.

That means that Americans import $450 billion of goods and services more than they export to the rest of the world. What explains the enormous US deficit year after year, and what would happen to Americans’ standard of living if it were to decline?

It is easy to blame the large trade deficit on foreign governments that block the sale of US products in their markets, which hurts American businesses and lowers their employees’ standard of living. It’s also easy to blame foreign governments that subsidize their exports to the US, which hurts the businesses and employees that lose sales to foreign suppliers (though US households as a whole benefit when foreign governments subsidize what American consumers buy).

But foreign import barriers and exports subsidies are not the reason for the US trade deficit.

The real reason is that Americans are spending more than they produce. The overall trade deficit is the result of the saving and investment decisions of US households and businesses. The policies of foreign governments affect only how that deficit is divided among America’s trading partners.

The reason why Americans’ saving and investment decisions drive the overall trade deficit is straightforward: If a country saves more of total output than it invests in business equipment and structures, it has extra output to sell to the rest of the world. In other words, saving minus investment equals exports minus imports – a fundamental accounting identity that is true for every country in every year.

So reducing the US trade deficit requires Americans to save more or invest less. On their own, policies that open other countries’ markets to US products, or close US markets to foreign products, will not change the overall trade balance.

The US has been able to sustain a trade deficit every year for more than three decades because foreigners are willing to lend it the money to finance its net purchases, by purchasing US bonds and stocks or investing in US real estate and other businesses. There is no guarantee that this will continue in the decades ahead; but there is also no reason why it should come to an end.

While foreign entities that lend to US borrowers will want to be repaid some day, others can take their place as the next generation of lenders.

But if foreigners as a whole reduced their demand for US financial assets, the prices of those assets would decline, and the resulting interest rates would rise. Higher US interest rates would discourage domestic investment and increase domestic saving, causing the trade deficit to shrink.

The smaller trade deficit would help US exporters and firms that now compete with imports.

But a decline in the trade deficit would leave Americans with less output to consume in the US or to invest in the US to produce future consumption.

And that is only part of the story. In addition to shrinking the remaining amount of goods and services available to US households and businesses, reducing the trade deficit requires making US goods and services more attractive to foreign buyers and foreign goods less attractive to US buyers.

That means lower US export prices and higher import prices, brought about by a fall in the value of the dollar. Even with the same physical volume of national output, the value of US output to domestic consumers would fall, because the US would have to export more output to obtain the same value of imports.

Trade experts estimate that reducing the US trade deficit by one percent of GDP requires export prices to fall by 10% or import prices to rise by 10%. A combination of these price changes is about what it would take to shrink the current trade deficit by 2% of our GDP, bringing the US close to trade balance. But, because US exports and imports are 15% and 12% of GDP, respectively, a 10% decline in export prices would reduce average real (inflation-adjusted) income by 1.5%, while a 10% rise in import prices would reduce real incomes by an additional 1.2%.

Thus, eliminating the trade deficit would require shifting about 2.5% of US physical production to the rest of the world, as well as a change in export and import prices that reduces their real value by another 2.7% of GDP. In short, with no change in the level of national output, Americans’ real incomes would decline by about 5%.

Over the longer run, the growth rate of national output depends on what happens to overall US investment in plant and equipment. If the trade deficit shrinks because consumption rises and investment falls, the lower level of investment would cause the growth rate to decline, further decreasing the long-run level of real income. But if the trade deficit narrows because households save more and government deficits are reduced, it is possible to have a higher level of investment – and thus higher incomes in the long term.

So changes in America’s saving rate hold the key to its trade balance, as well as to its long-term level of real incomes. Blaming others won’t alter that fact.

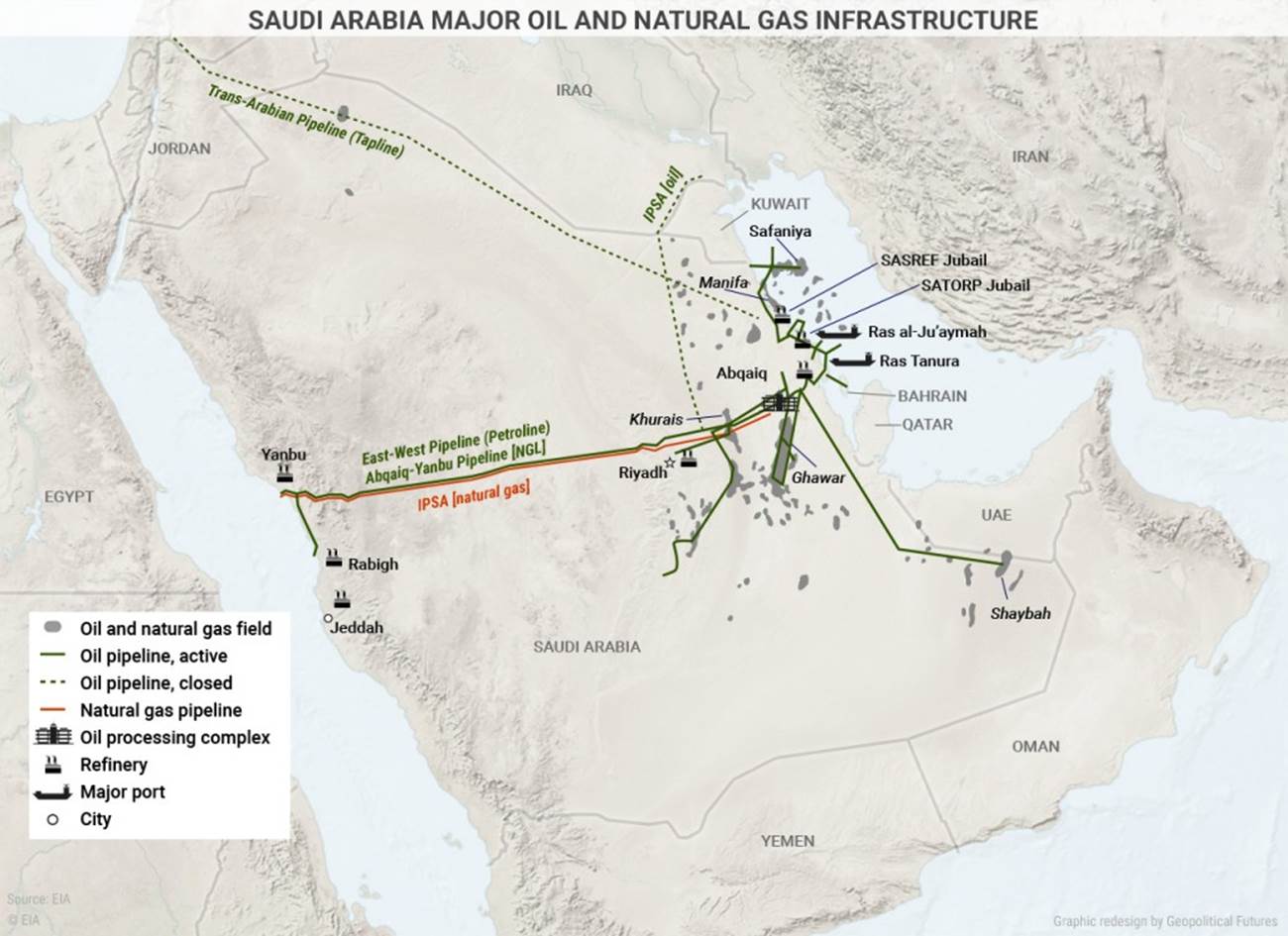

THE US- SAUDI ALLIANCE

The two countries need each other, but their interests are diverging.

On April 18, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis paid a two-day visit to the Saudi capital as part of a weeklong regional tour. At a press conference, the former senior American commander said that the kingdom is “stepping up to its regional leadership role.” Mattis also referred to Saudi Arabia as the United States’ best counterterrorism partner.

Mattis’ warm words require some explanation because U.S.-Saudi relations have been on the decline for over a decade. Historically, the United States has treated Saudi Arabia as a close ally, despite the massive difference in values between the two countries. But the relationship was damaged by the 9/11 attacks, which were carried out by a group that shares the same core Salafist ideology as Saudi Arabia. The 2003 decision by the administration of President George W. Bush to carry out regime change in Iraq, which empowered pro-Iranian Shiite forces in the country, further strained relations between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. The split was deepened further by the decision of President Barack Obama’s administration to sign a nuclear agreement with Iran in 2015. The deal gave the U.S. a potent ally in the fight against the Islamic State but has energized Tehran at a time when Riyadh’s fortunes are declining.

U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis (left) departs after meeting with Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Crown Prince and Defense Minister Mohammed bin Salman at the Ministry of Defense on April 19, 2017 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Pool/Getty Images

This more recent trend is in sharp contrast to the two countries’ relationship since the famous 1945 meeting between the modern Saudi polity’s founder, King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman al-Saud, and then-U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard the USS Quincy in Great Bitter Lake in Egypt. In the aftermath of World War II, the United States took over as the Middle East’s great power patron. Previously, Great Britain served in this role. The British had a very close relationship with King Abdulaziz during the first three decades of the 20th century. During this time, the latter led a band of tribal religious warriors who conquered much of the Arabian Peninsula and, in 1932, founded the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The Saudis relied on the British as their security guarantor, especially in the days before the monarchy could profit from the export of crude oil, which was discovered in 1938. It was only natural for the Saudis to embrace the Americans when the United States emerged as the leader of the Western world.

From the U.S. point of view, the Soviet Union had gone from being an ally in World War II to America’s biggest adversary. Washington pursued a containment strategy against the Soviets. This strategy required allies, especially in the Middle East where the Kremlin also sought alignment with left-wing Arab forces whose fortunes were rising at the time. Saudi Arabia, with its ultraconservative religious monarchy, was a natural ally in the American effort to counter pro-Soviet secular regimes that emerged in many Arab countries including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Algeria and South Yemen, as well as the biggest Arab non-state actor at the time, the Palestine Liberation Organization.

As a result, the Saudi regime – in addition to the other Arab monarchies (especially in the Persian Gulf) as well as Turkey and Iran – became a close ally of the U.S.-led Western camp. Ironically, in an effort to counter the Soviet Union and its secular proxies, the United States empowered Islamist actors. The U.S.-Saudi relationship further strengthened when anti-American Shiite Islamists overthrew the monarchy in Iran in the 1979 revolution. But nowhere was the American-Saudi alliance against communism more significant than in Afghanistan in the 1980s. The U.S. and Saudi Arabia, in cooperation with an Islamist military regime in Pakistan, backed religious insurgents against Soviet troops supporting the communist Afghan regime.

The Saudis spent billions of petrodollars to help the United States during the Cold War. In return, the United States remained the primary guarantor of the kingdom’s stability. In those days, the U.S. overlooked the undemocratic nature of the Saudi regime and its deeply austere Salafist ideology. The U.S. deployed 500,000 troops to protect the Saudis after Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait in 1990, leading to the Gulf War in 1991.

That year was a major turning point. The Soviet Union imploded, ending the Cold War. At about the same time, a global jihadist movement in the form of al-Qaida emerged as a threat to American global interests. As we showed in our recent Deep Dive, transnational jihadism was the natural outgrowth of Salafism, which had its roots in Saudi Arabia. Transnational jihadism was further empowered by the U.S.’ need for radical Islamist militiamen to fight the Soviets and their communist allies.

Therefore, the United States ignored the organic links between the Saudi regime and jihadists for another decade. Al-Qaida designed the 9/11 attacks to break the U.S.-Saudi alliance. The jihadist movement did not succeed in this goal, but the attacks weakened the U.S.-Saudi bond. A major divergence between U.S. and Saudi interests emerged. It gradually became clear to the Americans that simultaneously fighting jihadists and maintaining ties with Saudi Arabia was not possible.

The jihadists are not allies of the Saudi regime; more than anything, they want to topple it. However, given the overlap in the identity and ideology of jihadists and the Saudi kingdom, Riyadh is unable to counter the transnational movement. The Saudis cannot change their Salafist nature, and fighting jihadism could weaken the Saudi regime. Since Washington needed a partner in this fight, it entered into a complicated but cooperative relationship with Riyadh’s major nemesis, Tehran.

2011 was another watershed year. The United States pulled its forces out of Iraq, leaving the country in the Iranian orbit. By that time, the Arab Spring was a year old and had begun to hollow out the Arab world. The only major Arab state unaffected by the Arab Spring is Saudi Arabia, which has been forced to deal with the regional mess. Making matters worse was the 2014 plunge in oil prices, which badly wounded the Saudis.

Even though their interests have diverged, Washington still needs Riyadh because of the U.S. balance of power strategy. The United States does not want to see Iran take advantage of the chaos in the Arab world and accumulate a disproportionate amount of influence. Toward this end, the Americans are also leaning on Turkey to assume a more prominent regional role, especially in the fight against the Islamic State. Turkey is the region’s natural leader, but because of its domestic issues, the Turks are not in a position to intervene at this time.

This means that the Americans need the Saudis – even though Riyadh cannot ensure its own security and is working closely with the Pakistanis to get the Islamic Military Alliance off the ground. At the very least, the United States does not want to see the Saudis weakened. This would create more room for not only Iran but also IS. It is this fear that now forms the basis for the U.S.-Saudi partnership.

THE SAUDI SOCIAL CONTRACT UNDER STRESS

BY KAMRAN BOKHARI

Though Saudi Arabia has seen some economic respite lately, it is far from being out of the woods. Nonetheless, the kingdom decided to end public sector salary cuts and restore bonuses for civil servants and military personnel. Reversing course a mere seven months after instituting austerity measures shows that Riyadh cannot bear the political cost. This does not bode well for much-touted efforts to overhaul the monarchy’s political economy.

On April 22, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud reinstated the bonuses after 2016 revenues rose, leading to a budget deficit decline from $98 billion in 2015 to $79 billion last year. According to a press release from the official Saudi Press Agency, the Saudis managed to cut their projected deficit in half during the first quarter of 2017. King Salman also fired his civil service minister and ordered an investigation into alleged abuse of office. The monarch decreed that two months extra salary would be paid to members of the armed forces taking part in the war in Yemen.

Saudis attend a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the creation of the King Faisal Air Academy at King Salman air base in Riyadh, on Jan. 25, 2017. FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP/Getty Images

In an unprecedented move last September, the Saudi regime decided to implement austerity measures due to a sharp decline in oil prices. The measures affected hundreds of thousands of Saudis who make up two-thirds of the national workforce. The government’s rationale for the rather abrupt change of heart now is that the injection of cash to government employees would stimulate growth.

However, the fact remains that the allowances are a major drain on the kingdom’s exchequer.

The Saudis continue to cut spending elsewhere. In mid-April, Reuters reported that Riyadh’s Bureau of Capital and Operational Spending Rationalization, established last year, was looking into shelving billions of dollars worth of reform and development projects. This means that the Saudi regime is willing to incur the financial cost of placating public servants and military personnel. On April 3, the Cabinet announced a pay increase of up to 60 percent for air force pilots – many who are flying bombing missions in Yemen where a Saudi-led military coalition composed mostly of Gulf Arab states is struggling to restore the internationally recognized government to office.

The Saudis likely realized that they could not sustain the entire austerity drive for too long and had to be strategically selective in restoring spending to politically sensitive groups. In fact, the suspension of allowance packages probably was not designed to be a long-term measure.

Though Riyadh may not have known when it could reinstate them, it wanted to do so at the first sign of financial respite via a mix of a modest increase in oil prices and other spending cuts. This is because the kingdom’s social contract is structured in such a way that citizens over the decades have grown used to the government paying for much of their needs.

Oil revenues have historically allowed the Saudis to afford this kind of spending. This has created a certain expectation among the public that is impossible to alter. The austerity measures are part of the reform agenda spearheaded by the king’s son, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Lofty goals aside, the Saudis are realizing that it is extremely difficult to alter a unique political-economic system based on a welfare state that caters to almost all of the average citizen’s needs.

Pulling the plug on these financial incentives is very risky under the current regional climate in many Arab states that is marked by civil unrest and armed insurrection. It is noteworthy that none of the monarchies have thus far been affected by this contagion. The Saudis would like to keep it that way, and they know the only way to prevent unrest is to maintain the patronage system. That said, the regime likely is not worried about public sector employees taking to the streets, considering these employees depend on the government for their livelihoods.

More noteworthy is that military personnel also had cuts reinstated. This gives some indication of what the Saudi government is afraid of: disloyalty in the bureaucracy or the military. The government does not want to take any chances.

The regime has been selling the idea that political activity of any kind could lead the country toward a fate similar to that of Libya, Syria and Yemen. It has also built a reputation for taking care of people’s needs. Riyadh cannot afford to be seen as derelict in this responsibility.

A trade-off has occurred between politics and economics whereby the public does not engage in political action because the regime takes care of its economic needs. This in turn gives the regime more stability. While religion has been a major pillar of the Saudi state’s legitimacy, its ability to economically provide for the public has been the other.

That Saudi rulers are seen as unable to deliver on the social contract represents a major security threat from within the state. An erosion of confidence in the ability of the current faction of the royal family dominated by the king’s immediate clan and its allies opens the doors for other factions to entertain ideas of a coup, which would explain why special attention has been paid to ensure the armed forces are kept satiated. Therefore, the decision to revive the salary structure and offer bonuses is an early indicator that economic reforms may not be possible because of the political sacrifice they entail, which puts the Saudi regime in a very difficult position.

CAPITAL KEEPS FLOWING INTO LATIN AMERICA

BY : JOSÉ ANTONIO OCAMPO