4 EXCELENTES POST PROVENIENTES DEL EXTERIOR

SOBRE CHINA/USA (THE ECONOMIST); FRANCIA ; ARGENTINA Y EUROPA

Por:Dennis Falvy

Macri’s Disappointing First Year in Argentina

BY : MARTIN GUZMÁN

NEW YORK – Argentina’s economy is struggling. Last year, the country suffered stagflation, with GDP dropping by 2.3% and inflation reaching nearly 40%. Poverty and inequality increased; unemployment rose; and foreign debt grew – and continues to grow – at an alarming rate. For President Mauricio Macri, it was a disheartening first year in office, to say the least.

To be sure, Macri faced a daunting challenge when he took office in December 2015. The economy was already on an unsustainable path, owing to the inconsistent macroeconomic policies that his predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, had pursued. Those policies led to imbalances that eroded the economy’s competitiveness and foreign reserves, pushing the country toward a balance-of-payments crisis.

But Macri also pursued a flawed macroeconomic policy approach. His administration needed to address the fiscal and external imbalances, without undoing the progress in social inclusion that had been made over the previous decade. His approach, based on four key pillars, has not achieved that.

First, Macri’s government abolished exchange-rate controls and moved Argentina to a floating currency regime, with the Argentine peso allowed to depreciate by 60% against the US dollar in 2016. Second, Macri’s government reduced taxes on commodity exports, which had been important to Kirchner’s administration, and removed a number of import controls. Third, the Central Bank of Argentina announced that it would follow an inflation-targeting regime, instead of continuing to rely mainly on seigniorage to finance the fiscal deficit.

Finally, Macri’s government reached a deal with the so-called vulture funds and other holdout creditors that for more than a decade had blocked the country from accessing international credit markets. Once the deal was concluded, Argentina pursued massive new external borrowing, with the emerging world’s largest-ever debt issue, to help address its sizable fiscal deficit. In the interest of lowering its borrowing costs, the authorities issued the new debt under New York law, despite the expensive battle that the country had just lost precisely because it had borrowed under that legal framework.

Macri’s macroeconomic policy approach – which also included increasing prices for public services that had been frozen by the previous government and implementing a tax amnesty program that provided the government with more fiscal revenues – rested on several controversial assumptions. Above all, the radical change in policy course was supposed to establish the conditions for dynamic growth.

The currency depreciation, it was assumed, would address external imbalances, by encouraging, with the help of lower export taxes, increased production of tradable goods. The deal with the vulture funds was supposed to reduce the cost of financing and boost investor confidence, thereby attracting inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI). Investment-led growth would help the entire economy.

These assumptions haven’t been borne out. Contrary to the government’s expectations, the peso’s depreciation had a large impact on consumer prices – as critics had warned. This reduced households’ purchasing power and weakened aggregate demand, while diminishing the devaluation’s overall impact on the country’s external competitiveness.

The central bank’s new focus on inflation is unlikely to help matters, either, because it will undermine economic activity and exacerbate the pain experienced by the most vulnerable, for whom unemployment may be worse than rising prices.

Moreover, Argentina’s fiscal deficit has increased, owing to the drop in revenues brought about by the recession. And there were no significant FDI inflows, because, as Macri’s critics had cautioned, the uncertainty surrounding his policies deterred investment.

The government has done one thing right: it rebooted the National Institute of Statistics and Census, which had lost credibility after interventions by the previous administration. But the overall situation remains bleak. At the end of Macri’s first year in office, Argentina faced the same macroeconomic imbalances that it did when he took office, but with significantly higher external indebtedness.

Furthermore, public anger is reaching fever pitch, owing to the effective redistribution of wealth away from workers brought about by Macri’s policies. Demonstrations abound, even causing the first day of school to be delayed. On April 6, the government faced its first nationwide general strike.

As it stands, Argentina’s prospects are uncertain. External borrowing is becoming a serious problem – one that is likely to intensify, as continued interest-rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve raise the costs of rolling over debts. Unstable macroeconomic dynamics are reproducing the same imbalances as they did before. For example, the capital inflows associated with external borrowing are putting upward pressure on the peso, threatening sectors that are important for job creation.

In the run-up to this year’s legislative elections, Macri’s government could try to stimulate economic activity by taking on more debt. But a debt-based recovery would be short-lived, and would sow the seeds of more acute debt troubles in the future.

To escape its perverse debt dynamics, Argentina must reduce its fiscal deficit. But it can do so only in the context of a sustainable and inclusive recovery of economic activity – and that requires a more competitive economy. Under current conditions, attempting to resolve the problem through a fiscal contraction would merely aggravate the recession.

Macri’s government should be working to develop a long-term macroeconomic strategy based on credible, not controversial, assumptions. Without a substantial mid-course correction, Argentina will settle onto a destabilizing debt path that leads nowhere good.

DISORDER UNDER HEAVEN:AMERICA AND CHINA’S STRATEGIC RELATIONSHIP.

By: The Economist

After seven decades of hegemony in Asia, America now has to accommodate an increasingly powerful China, says Dominic Ziegler. Can Donald Trump’s administration manage that?

The last time China considered itself as powerful as it does today, Abraham Lincoln was in the White House. At that time, and against the mounting evidence of Western depredations, the emperor still clung to the age-old belief that China ruled all under heaven, a world order unto itself. It never had allies in the Western sense, just nations that paid tribute to it in exchange for trade. Both China and “the outside countries”, he wrote to Lincoln, constitute “one family, without any distinction”.

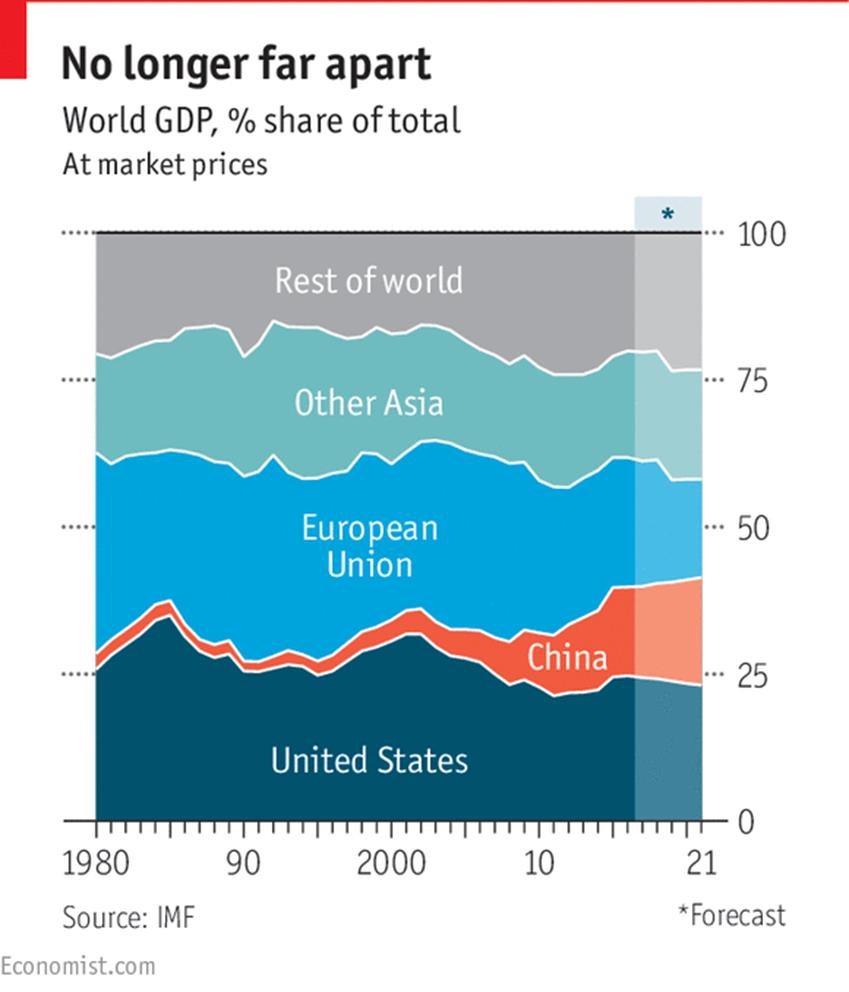

Today, after a century and a half that encompassed Western imperial occupation, republican turmoil, the plunder of warlords, Japanese invasion, civil war, revolutionary upheaval and, more recently, phenomenal economic growth, China has resumed its own sense of being a great power. It has done so in a very different world: one led by America. For three-quarters of a century, America has been the hegemon in East Asia, China’s historical backyard.

But now China is indisputably back. New towers have transformed the skylines of even its farthest-flung cities. An ultra-modern network of bullet trains has, in a few short years, shrunk a continent-sized country. China’s new power rests on a 20-fold increase in economic output since the late 1970s, when pragmatic leaders set in train market-led reforms. Over the same period the number of Chinese people living in extreme poverty, as defined by the World Bank, has fallen to 80m, a tenth of what it used to be. China is the world’s biggest trading nation and its second-biggest economy after America. There is hardly a country in the world to which it does not matter, either as a source of consumer goods or as a destination for commodities, capital goods and investment.

On all these counts, China wants—and deserves—a greater role in East Asia and in the global order. America has to make room for it. But the task will require wisdom and a subtle balance of firmness and finesse on both sides. A first indication of what to expect was on display at a summit between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump on April 6th and 7th at Mar-a-Lago, the American president’s Florida golfing resort. Though little of substance was discussed, Mr Trump hailed the bilateral relationship as “outstanding” and Mr Xi declared there were “a thousand reasons to get the China-US relationship right”. Neither mentioned the cruise-missile strike America had just launched against a Syrian air base. Nor was there any talk of imminently imposing tariffs.

For all the superficial bonhomie at the summit, the two countries see things very differently.

China’s system of politics, both bureaucratic and authoritarian, has helped economic development at home, but is alien to American notions of democracy. American policymakers have traditionally seen liberal democratic values and an emphasis on human rights as factors that legitimise and strengthen the international order. Chinese policymakers see them as Western conspiracies to foster the kind of colour revolutions that brought down authoritarian former Soviet regimes, and might attempt to do the same in China.

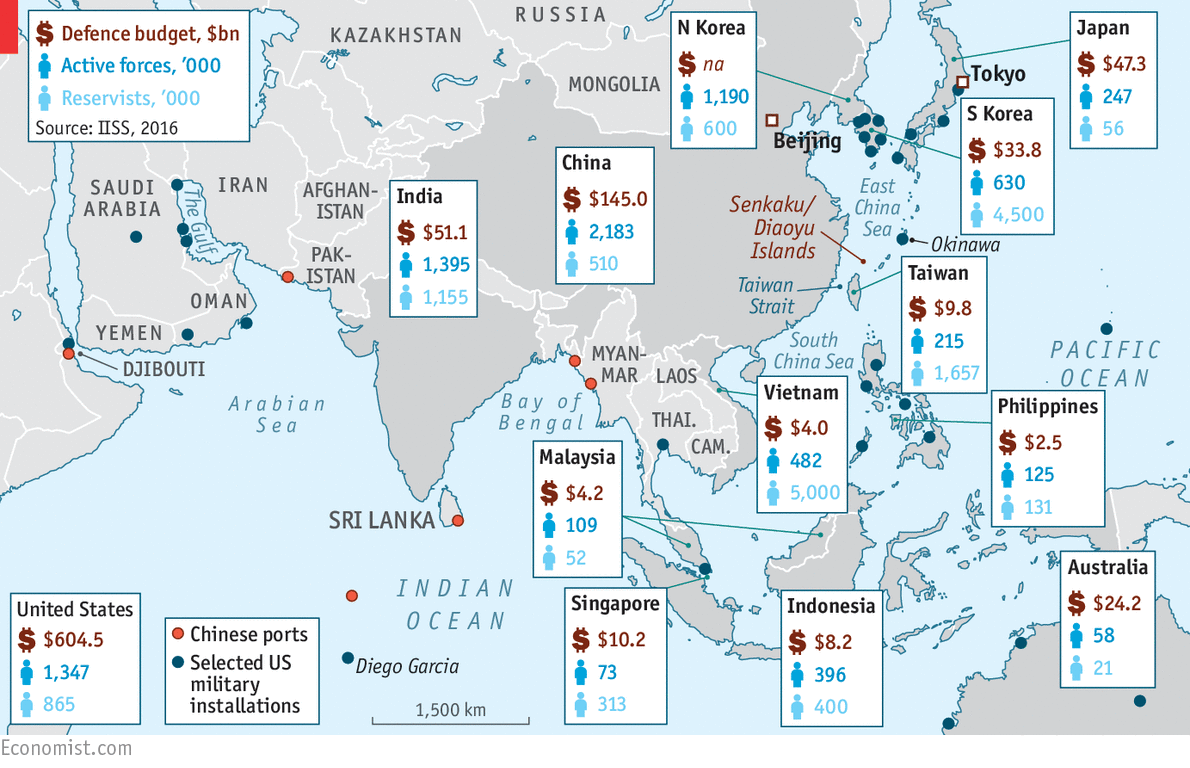

Chinese strategists consider the country’s rapidly modernising armed forces as essential for protecting the sea lanes on which its prosperity and security depend. They think a powerful navy is needed to keep potential adversaries from China’s shores and stop them from grabbing Chinese-occupied islands. They also suspect that America’s massive military presence in the Asia-Pacific region is designed to check China’s rise.

.

American strategists, by contrast, say their country must keep a presence in the region because Chinese hard power unsettles America’s friends in East and South-East Asia. In the past few years China has challenged Japan over the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands (which the Chinese call the Diaoyu Islands), and carried out extensive construction works to build bases and runways on disputed rocks and reefs in the South China Sea. Those American strategists suspect China of wanting to turn the vast sea into a Chinese lake; and, more broadly, of seeking dominance in East Asia and overturning the existing order.

A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE

America has long sought to prevent any one power having hegemony in Asia, whereas China wants to keep potential adversaries far from its shores. Somehow, they have to find a way of accommodating each other’s overarching goals, as Henry Kissinger explains in his classic book on statecraft, “World Order”. Peace hangs on the outcome.

That peace cannot be taken for granted. In much of East Asia, history is unfinished business.

Taiwan, to which the Nationalist losers in China’s civil war fled in 1949, is a thriving and peaceful democracy. Yet China’s Communist Party sees its sacred mission as bringing Taiwan back into the motherland’s fold, and reserves the right to use force to do so. American guardianship of the island is meant to ensure that China never dares. But as Chinese might grows and American commitment appears to wane, the room for miscalculation grows. Soon after his election Mr Trump even seemed to be calling into question America’s endorsement of the “one-China policy”—China’s insistence on the polite fiction that Taiwan is part of China.

A potentially more imminent flashpoint in the region is the Korean peninsula, divided since the end of the second world war. North Korea, ruled by a family mafia now in its third generation, has a broken economy and an ill-trained army. But it has poured money into nuclear programmes that threaten South Korea, unnerve Japan and before long will also pose a threat to America. North Korea exasperates China’s leaders, yet they feel they must show solidarity to a former ally against America in the bloody war North Korea launched in 1950. China would rather have a nuclear North Korea under Kim Jong Un than a failed state sending millions of desperate refugees across the Chinese border. Above all, it is troubled by the idea of a unified, democratic Korea with American troops next door. At Mar-a-Lago, Mr Trump asked Mr Xi for ideas to deal with the threat from North Korea, but his missile strike in Syria made it clear that America might act alone against the North. Handling Mr Kim’s belligerence—and the regime’s eventual demise—will be a huge test of great-power co-operation.

.

Yet conflict between China and America is not inevitable. Both sides want to avoid it and can adjust accordingly. It helps that habits of co-operation have become established over four decades of Chinese market reforms, which could not have happened without American security guaranteeing China’s external environment. Theirs is the world’s most important bilateral economic relationship today, with combined annual trade adding up to $600bn and investment in each other’s economies totalling around $350bn.

China has no missionary zeal or ambitions to export revolution, nor indeed any grave ideological misgivings about the current order, which it resents chiefly because it does not have a greater say in running it. Ensuring more of a role appears to be the chief mission of Mr Xi, China’s paramount leader since 2012. He has accrued more authority to himself than any leader since the late Deng Xiaoping, and is now gingerly putting forward a model for greater global leadership which party theorists are starting to call the “China solution”. At one level, this is about practical matters, such as investing in Central Asia to reduce poverty. At another, it is about opposing American dominance.

China, Mr Xi told a conference in February, should “guide international security” towards a “more just and rational new world order”. That kind of language is redolent of the old imperial Chinese virtues. But whereas China’s previous experience of power was of ruling all under heaven, it now has to accept being merely one great power among several. America, for its part, has never had any experience of ceding as much influence and authority as it may have to do to China in future.

An already fraught relationship has become more so with Mr Trump’s election as president. For seven decades America’s grand strategy has rested upon three pillars: open trade, strong alliances and the promotion of human rights and democratic values. It is not clear to America’s friends in Asia to what extent Mr Trump, with his disdain for diplomatic process, a protectionist streak and a narrow “America first” definition of the national interest, is prepared to uphold those three pillars. As Michael Fullilove, head of the Lowy Institute, a think-tank in Sydney, puts it, Mr Trump is “an unbeliever in the global liberal order and a sceptic of alliances. And he has a crush on authoritarians.”

Mr Trump’s victory came as a huge shock to China’s leaders. They hate unpredictability and would have much preferred Hillary Clinton, the devil they knew. It also came at an inconvenient time for the Chinese. Mr Xi is focusing on a crucial five-yearly Communist Party congress later this year. He appears set on consolidating his grip on power, against a backdrop of an unsettling credit bubble and economic growth that has slowed sharply from a peak of 10% a year to just 6.5%.

For the most part, China has concealed its alarm over Mr Trump behind studied caution.

“When you see 10,000 changes around you,” Chinese leaders told Kevin Rudd, an Australian former prime minister and China hand, citing one of their language’s countless proverbs, “ensure you yourself don’t change.” China’s leaders have decided to wait and see. But behind the scenes they have been trying hard to influence Mr Trump, working mainly through his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, a property developer with Chinese ties.

The Chinese also soon grasped the new president’s transactional approach, prompting them to dispatch Jack Ma, the boss of Alibaba, an e-commerce giant, to meet him. He promised that his firm would generate 1m jobs in America. Soon afterwards trademark applications to protect the Trump brand in China that had languished in the courts for years were suddenly granted.

Cause and effect are impossible to disentangle, but Mr Trump has certainly toned down his pre-election anti-China rhetoric.

LOOKING INTO THE ABYSS

Yet deep, abiding uncertainties about the two countries’ relationship remain, not least over trade, which for three decades has underpinned relations between the two countries. Mr Trump appears to view trade not as mutually beneficial to all parties but as a zero-sum game, and gives short shrift to the post-war multilateral trading system. One of the first things he did after coming to office was to cancel the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free-trade agreement among 12 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (though not China)—a big blow to America’s economic role in Asia.

.

More broadly, the world view of some of Mr Trump’s advisers encompasses a Manichean expectation of conflict. They claim that China is so set on strategic rivalry with America that military conflict is inevitable, and argue that the best way to protect the national interest is to spend more money on the armed forces and less on diplomacy. Such people do not have a monopoly on the internal debate about America’s strategic relationship with China, any more than they do on trade. As this special report went to press, an alternative approach to trade, involving a robust multilateralism, was gaining favour. Meanwhile James Mattis, the defence secretary, on his first trip to Asia in early February urged care when challenging Chinese construction in the South China Sea with military force, and emphasised the primacy of diplomacy over military action in resolving differences.

Mr Mattis, a well-rounded former general, is what Washington’s seasoned hands call one of the administration’s “grown-ups”, but there are precious few of them. The secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, a former oil boss, was counted among them, though question marks have since been raised about his Asia diplomacy. And although every new administration takes time to fill vacant posts, the gaps in the Trump foreign-policy team, especially on the Asia desks, are alarming. Among other things, almost all the Republican party’s seasoned Asia hands, who during the Obama years were working in think-tanks, universities or the private sector, swore before the election that they would never serve under a President Trump. Some have since swallowed their pride and moved closer to the new administration, but Mr Trump’s henchmen have long memories when it comes to criticism of their boss.

Many observers still hope that, once an unusually chaotic new administration sorts itself out, it will revert to a policy that flows recognisably from America’s seven decades of experience in Asia. But that is far from certain. Some of the administration’s leading members hold seemingly irreconcilable views on American policy in Asia. Perhaps that reflects broader American disagreement about global roles and responsibilities. Yet the president himself seems unaware of the lack of any comprehensive strategy in Asia, and that problem may persist. A Republican Asia hand who served under both Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush explains that “I don’t get a sense of a learning curve with Trump. So I don’t expect things to get any better.”

Amid all this uncertainty about Mr Trump’s policy in Asia, the two chief risks for the region appear almost contradictory. The first is that, after an initial honeymoon with Chinese leaders, an increasingly aggressive stand by the new administration raises Chinese hackles while failing to reassure America’s Asian friends. The second is that American policy in Asia becomes half-hearted and disengaged, again unsettling Asian friends and perhaps emboldening China. The consequences in either case might be similar—shifting power dynamics that require rapid adjustments, risking instability and even regional turmoil. Hope for the best, but prepare for disorder under heaven.

A NEW ROADMAP FOR POLITICAL FACTIONS

By : GEORGE FRIEDMAN

On June 20, 1789, toward the beginning of the French Revolution, a meeting of the emerging National Assembly was held at a tennis court in Versailles. Various factions sat together. The supporters of the monarchy sat on the right. Supporters of creating a democratic republic sat on the left. In between were a variety of factions of many shades of monarchy and republicanism. This was the origin of the terms left wing and right wing. And they have been used ever since to describe global politics. Over the years, the terminology has confused more than it has enlightened.

It didn’t work all that well in the French Revolution either. Napoleon was an officer in the revolutionary army and eventually became the army’s leader. He had enormous support from the public, but appointed himself emperor, to great public enthusiasm. To this day, his tomb in Paris is honored by Republican France. Now, was Napoleon right wing or left wing? That question can’t be answered, nor does it need to be. He was Napoleon Bonaparte and he did what he did.

The concept of the “left” has morphed from being purely an idea about how the government should be run into being the party of the poor and the working class. European socialism can make a reasonable case for being the heir to the French revolutionary republicans. But there were conservatives who opposed free market capitalism and also were concerned with the working class while trying to preserve the existing society. Some of those were called leftists by rightists who didn’t want to help the working class. And then there were leftists like Lenin who claimed to have created a revolution for the workers and then unleashed a reign of terror on them.

Consider that Milton Friedman was a great economist who developed a theory of the relationship between money and economic growth. He was also a deep believer in a limited government that does not intrude on private life. Adolf Hitler believed deeply in state control over all aspects of life. Both Friedman and Hitler were known as right wing. I would have loved to be a fly on the wall at their conversation had they both been at Versailles, as part of the “right.” Or consider two leftists, Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin. You could argue that they were different points on an ideological continuum. I’d argue that Stalin and Hitler inhabited the same parallel universe, and Roosevelt had more in common with well-known right winger Dwight Eisenhower.

It is not surprising that a happenstance political taxonomy created more than two centuries ago is insufficient for contemporary politics.

There are very few monarchists left around. There are many people claiming to be democratic republicans, but meaning very different things by it. Everybody claims to speak for the poor and few do anything about it.

The reason this matters is that most people in a democratic society see themselves as belonging to a faction, rather than adhering to an ideological consistency or their own views on the budget deficit. People are drawn together by common values, but it is sometimes difficult for them to define what those values are. They are drawn into political factions based more on social forces than a clear ideology.

Many poor white people are attracted to Donald Trump because they know others who support him and his message resonates with their collective sensibility. Many older white professional women are drawn to Hillary Clinton because they see her as one of them. Many millennials are drawn to Bernie Sanders because others they know are drawn to him and because he says things that resonate with the group.

Obviously, everyone doesn’t work this way. Some sort things out themselves. But many, and even most, do it this way.

As I wrote a short while ago, a member of my staff who traveled broadly in Europe and knew many British citizens said she had never met anyone who was in favor of leaving the EU. Since the majority turned out to favor Brexit, this means she only associated with people who agreed with her. And it is likely that they agreed with her on many other issues as well. Political life has always been about belonging and sharing values. But in practice, this is not about having values and then joining a faction, but about joining a faction and then absorbing its values.

For most of us, navigating the complexities of policy issues is impossible. There are so many, they are so nuanced, and frequently they are presented in incomprehensible ways. The idea is that in a democratic society people study the issues and decide which candidate is right. But this is a caricature of what happens, given the impossibility of the model presented.

How do we decide where we belong politically? It is frequently by where we were born, who our friends are and our shared emotions about events. But there still must be a roadmap that tells us where we are. If one pole of our political position is the shared values of the people we know, the other must be some shorthand to tell us how we differ from others. Right wing and left wing are no longer useful and indeed haven’t made sense for a century.

Consider Trump and Sanders. Both claim to speak for the lower classes that have suffered abuse by banks. Both believe that the economic policies of the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations have harmed the United States and that free trade has harmed the American worker. Each wants to reduce U.S. military involvement overseas. Sanders is on the left. Trump is on the right. Therefore, the young, who are attracted to the left, support Sanders. The older generation, who are attracted to the right, are drawn to Trump. Again, this does not apply to every voter, nor does this address the important issues. It certainly doesn’t address personality. But it does show how the roadmap and the social grouping interact.

The roadmap is needed, but it cannot be drawn from a tennis court in Versailles in 1789. There are no monarchists, and most people at least claim to be supporters of democracy and the republic. The real division today, I would argue, is between those who regard the nation-state as the most desirable political order and those who believe that economic and political integration with other countries is most desirable. On this continuum for example, it would become clear that Trump and Sanders are nationalists, regardless of how they express it, and Clinton is an internationalist along with, for example, Mitt Romney.

Leaving out personality and character, the various factions of the United States have the ability to place themselves on this roadmap. Nationalist and internationalist are coherent distinctions that apply to many of the issues and policies being discussed now. It is an ethical distinction and even an aesthetic one. Left and right make no sense in this distinction. Someone concerned about jobs going overseas would not be a leftist, but a nationalist. Someone who believes that international connections create jobs would not be a rightist but an internationalist. A social group organizing around left and right would not serve the purpose of guiding the cohort. Nationalist and internationalist might do it.

I am not arguing in favor of any groups or for or against any of my examples (well except against Hitler, Stalin and Lenin). The point of this is not to advocate for a position, but to facilitate a discussion about how we choose who to support politically and how we distinguish between the policies and values of candidates in the United States and Europe, and perhaps elsewhere as well.

THE SECOND YEAR OF EUROPE

By : Richard Haass ( Project Syndicate)

NEW YORK – More than four decades ago, US National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger declared 1973 to be “The Year of Europe.” His aim was to highlight the need to modernize the Atlantic relationship and, more specifically, the need for America’s European allies to do more with the United States in the Middle East and against the Soviet Union in Europe.