LA MISTERIOSA QUIETUD EXISTENTE

EN EL MERCADO DEL ORO : PESE A LOS ACONTECIMIENTOS

Por:Dennis Falvy

Titulo en castellano en este largo pero interesante post, , lo que The Economist en su serie Buttonwood acaba de publicar y la verdad es que muy ilustrativo el artículo, dado que hay una serie de analistas que apuntan a que el oro se dispararía en su cotización, por todo lo que viene pasando en el ámbito internacional. Vale la pena leer el punto de vista de la revista. Pues el subtitulo señala que :¿Cuál es la razón por la que el metal oro no ha respondido a los claros riesgos geopolíticos, que se magnifican con la respuesta del vicepresidente de los EEUU a las bravatas tan fuertes del gobernante y voceros oficiales de Corea del Norte; así como a lo que se ha señalado del incremento del gasto público por el presidente Trump.

Como es de dominio público , Mike Pence señaló que “ El escudo está en guardia y la espada está lista".Frente a 2.500 uniformados, comentó que el gobierno de Donald Trump seguirá "trabajando con diligencia" junto a aliados como Japón y China, entre otras potencias, para aplicar una presión económica y diplomática sobre Pyongyan.

"Como todos saben, la preparación es la clave", aseguró. Además, explicó que Washington honrará su alianza con las naciones de la Cuenta del Pacífico y que defenderán la libertad de navegación en el mar de China Meridional.

Según consigna Infobae, Mike Pence agregó que "quienes desafíen nuestra determinación o preparación deberían saber que venceremos cualquier ataque y equipararemos el uso de cualquier arma convencional o nuclear con una abrumadora y efectiva respuesta estadounidense".

Asimismo presentamos los post extensos, pero súmamente interesantes, de “La tormenta que se viene” y el por que Europa es una super potencia y permanecerá así por muchas décadas,posts que valen la pena analizarlos en sus perspectivas correspondientes.

THE MYSTERIOUS QUIESCENCE OF THE GOLD MARKET

By: The Economist

Why gold has not responded to geopolitical risk or reflation talk.

AMERICA has bombed Syria, and its relations with Russia have deteriorated. North Korea is developing a long-range nuclear missile, a development which Donald Trump has vowed to stop, unilaterally if necessary. There is talk of a “reflation trade”, with tax cuts in America pepping up global growth.

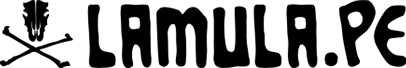

All this ought to be good news for gold, the precious metal that usually gains at times of political uncertainty or rising inflation expectations. But as the chart shows, gold took a hit when Mr Trump was elected in November and is still well below its level of last July. As a watchdog, gold has failed to bark.

Bullion enjoyed a ten-year bull market from 2001 to 2011, when it peaked at $1,898 an ounce.

This long upward run was bolstered in its later stages by two developments: first, the use of quantitative easing (QE) by central banks, which gold bugs argued would inevitably lead to high inflation; and second by the euro crisis, which caused nervousness about the potential for a break-up of the single currency and about the safety of European banks. By 2013, however, euro-zone worries were fading and, despite QE, no inflation had been seen. The gold price fell sharply and has stayed in a narrow range since.

Last year was a disappointing one for jewellery demand, with an annual survey by Thomson Reuters finding that jewellery fabrication fell by 38% in India (where it was hit by a new excise duty) and by 17% in China. The Chinese central bank was also a less enthusiastic gold-purchaser than before: net central-bank buying dropped to a seven-year low.

The big change in the gold market since the turn of the millennium has been the rise of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which have made it easy for investors to get exposure to the metal without worrying about storing it or insuring it. At the peak, gold ETFs held around 2,500 tonnes of gold, according to Citigroup, worth around $100bn at today’s prices.

Gold ETFs were bought as a classic “momentum trade” by investors who try to make money by following trends. Once the price trend changed in 2013, such investors scrambled to get out of the metal. At the moment ETFs hold just 1,800 tonnes.

The problem with gold is that there is no obvious valuation measure. The metal pays no real “earnings”. Although gold is seen as a hedge against inflation, it cannot be relied on to fulfil this function over the medium term; between 1980 and 2001, its price fell by more than 80% in real terms.

The general rule is that gold is seen as an alternative currency to the dollar, so when the greenback does well, bullion does badly. But this also means that gold’s performance can look rather better in other, weaker currencies. Since the Brexit referendum, for example, bullion is up by 19% in sterling terms. Another factor is real interest rates. When they are high, the opportunity cost of holding gold is also high. Conversely, very low interest rates mean that there seems little to lose by holding gold.

Those two factors explain why the “Trump trade” was initially not very good for gold. In the immediate aftermath of the election, investors hoped that tax cuts would revive the American economy; this would force the Federal Reserve to push up interest rates and that rate boost would drive the dollar higher. Neither prospect would be good for gold.

But the Trump trade has lost momentum. The president’s failure to repeal Obamacare has raised doubts about the prospect of a tax-reform programme being passed by Congress. Gold has duly perked up a bit since the start of the year, and the price rose by 1.6% on April 11th.

But, although inflation may be a bit higher, nothing suggests a return to the kind of double-digit rates seen in the 1970s, when gold enjoyed a spectacular price rise.

Even so, the metal has not performed as well as it might have done, given the geopolitical headlines. Perhaps this is because Mr Trump has backed away from some of his pre-election threats—on trade with China, for example. The bombing in Syria may turn out to be a one-off, and his statements on North Korea could be “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”. With the help of advisers such as Rex Tillerson, the secretary of state, and James Mattis, the defence secretary, Mr Trump may turn out to be a more conventional foreign-policy president than expected.

So buying bullion is really a bet that things will go spectacularly wrong: that events escalate in the Middle East and North Korea or that central banks lose control of monetary policy. It could happen, of course, but it helps explain why gold bugs tend to be folks with a rather gloomy attitude towards life.

VIENE LA TORMENTA - THERE'S A STORM COMING

BY: FRANK DE BAERE

From Tulips to South Seas, from Dot Coms to Houses, all manias have something in common.

Assets rise gently, largely unnoticed by the great unwashed, as the easy money is made and price rises above historical norms they become more popular by mainstream, then they become overvalued as their price rises way above "intrinsic value" and when the mania finally matures overvalued grows to extremely overvalued. And then at some point in time at some price level on the chart the market exhausts itself and collapses back to and often below it's starting point.

These collapses tend to be sudden, out of the blue and violent and usually happen without any obvious cause or reason. What was made during the boom gets lost in the bust. Only the smart money has greater odds of surviving ending manias but only if it does not get outsmarted.

What we as Danielcode members are interested in is markets turns. As we said above manias end at some point in time and at some price. Think about that for a minute. A mania pushes up price to a certain level and at one specific point on the chart it all collapses under its own weight for no obvious reason. Whatever reason is pinpointed to the start of the crash by financial journalists is merely linking an event or piece of news that happened after the top was made. The real question on our mind is "Why is a specific price THE top and why did that top happen in that specific week or even on that specific day?" And God help us, what if we could foresee these points on the chart and have a good idea where and when they should happen. Is that even possible? The truth is that God does help us, the sad truth is that no one listens and even less are interested.

The Danielcode is a mathematical matrix of numbers straight from the book of Daniel discovered by our mentor John Needham. How these numbers are calculated is beyond my time schedule to write here but you can discover all of that in the "Live at the Springs" audio under the articles tabs at the Danielcode website. The Danielcode ratios are 29.7 , 37.5 , 44.5 , 50 , 62.5 , 59.3 , 74.2 and the powerful 89 number. And these numbers are important folks. Very important. They rule all markets in both time and price, they even rule all life and death in the universe. Or do you think it is a coincidence that the synodial month, the average length of a month, is 29.7 days or that the orbit of Saturn (referred to by the ancients as Cronus or Kronos the Roman Deity of Time) is 29.7 earth years or that the orbital velocity of Mercury is 29.7 miles per second?

Maybe. But our mentor has shown us so many charts where price has recognized so many Danielcode numbers always with precision down to a few ticks that I have completely sworn off Random Walk theory a long time ago. Nothing is random in a chart my friends. Markets are not random, they are perfectly mathematically organized, and sometimes even perfectly predictable. Let me show you what I mean.

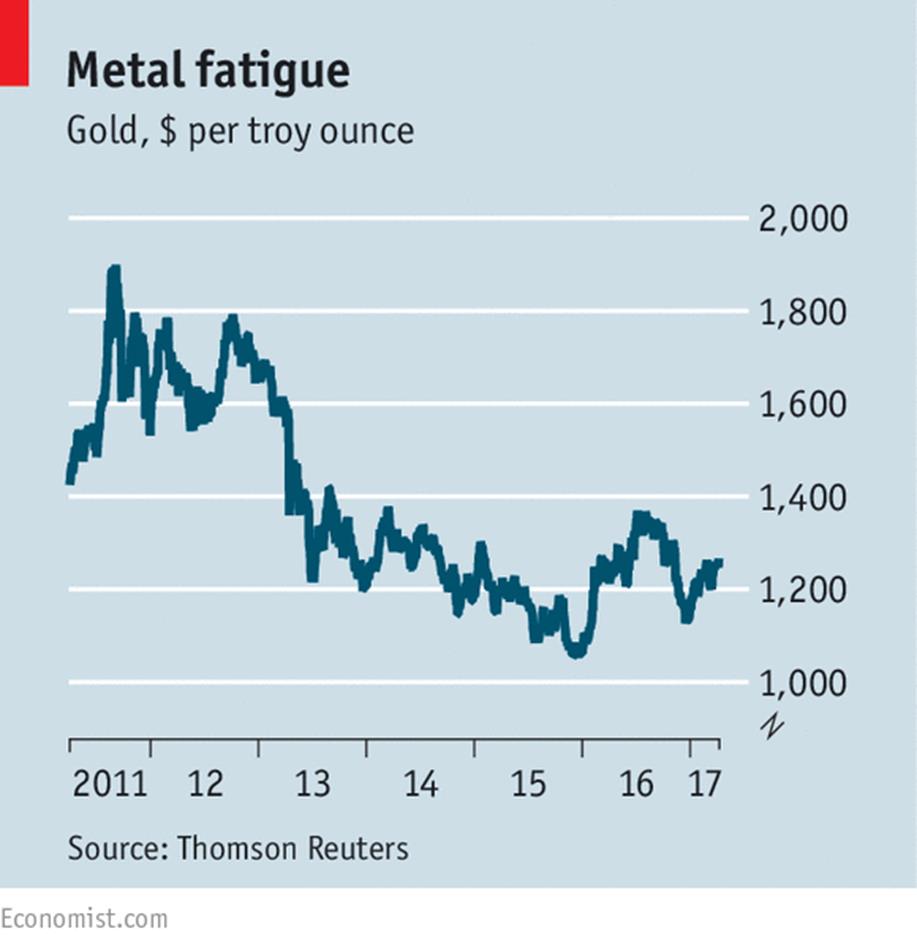

This is a 24 day chart of the US Dollar Index DX. Non-daily Danielcode charts are always composed of bars that contain 6 trading days or multiples of that (12, 24 and 48 trading days).

The reason for that is beyond the scope of this article but it all comes straight from the Bible.

You can read about it in the two "Master Class" articles on the Danielcode website under the articles tab. (Master Class I and II). Notice how the strong rally in DX since 2014 found it's perfect top at 100.51 just 3 ticks shy of the 59.3% retracement from the 2008 low to the 2001 high. And how this happened on a 59 time cycle. Yes, that's right, these numbers can also be projected on the time axis of the chart where they become time cycles instead of price levels.

If you think this is complex, let me tell you that I had never seen a trading chart before I met the Needham family in Taupo, New Zealand for a Danielcode Tutorial a few years ago. That was the first time that Mr Needham had taught The 4th Seal, and since then I have loved, lived and worked with it every day. It is indeed a marvel.

Now take a look at the next long term DX chart and how this market reacts to known Danielcode numbers in the form of price extensions. Does this seem random?

Larger Image

I don't think so. The precision with which the price levels from the Danielcode sequence are recognized is stunning. Markets recognize these numbers all the time and if you draw the right DC sequence that a market is following on your chart you will see that markets lock on to these sequences for months sometimes even years in a row before switching to another DC sequence.

It's truly amazing how precisely all markets vibrate on the Danielcode sequence. And it happens all the time right before your eyes and totally unnoticed by even the biggest and smartest traders on the planet.

THE CURRENT STATE OF THE MARKET

A question many financial experts are asking themselves is: "What's next?". In fact it is the most important question on every mind that cares about the market. The truth is, we don't know. Nobody does. Only our Creator has foreknowledge. But there are clues and chance favors the prepared mind. Allow me to help prepare your mind.

Here at the Danielcode we try to become experts at timing market turns and we approach this from a totally different angle. We use the numbers from the Danielcode straight from the Book of Daniel in the Bible. Sounds scary right? It's not. In fact it's quite a miracle.

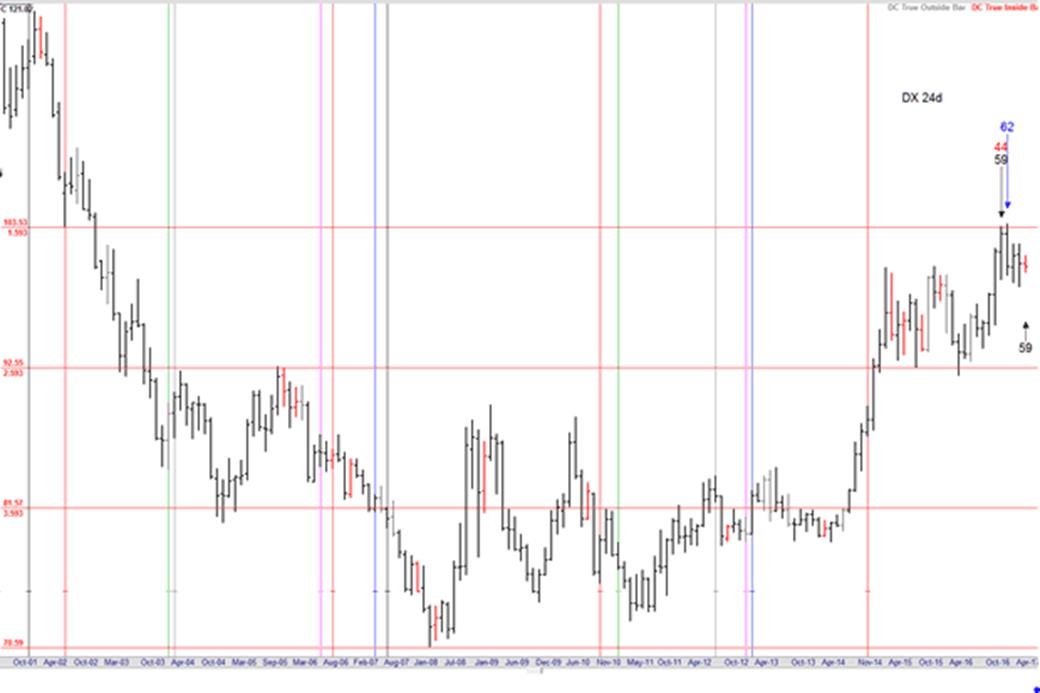

Below is a 24 day chart of the NASDAQ NDX. It has a DC regression channel drawn on it that is constructed on the important 59.3 DC ratio.

This chart shows The Death Cycle on NASDAQ. The last Death Cycle we saw was on the S&P in October 2007 and you know how that turned out!!

Larger Image

Notice how this market is at the 3rd standard deviation of the DC regression channel. This means that this market is 3 standard deviations away from the median of its uptrend. This in and of itself is a sign of extreme speculation and tells us NDX is on a unsustainable path.

Markets rarely go beyond the 3rd standard deviation. But there is more. Both the 24 day chart and the 6 day chart have a 59 death cycle expiring early April. Death cycles are 59 topping cycles expiring from the first hub. When they bite they kill the market and turn its trend around to clear whatever excess was build up during the boom.

On the 6 day chart of NDX we already broke the low of the previous bar which means this 59 death cycle is alive and kicking. Once the 24 day chart does the same odds are that this market has a serious meeting with mother nature's laws of gravity and that my friends should get you on high alert for the potential end of this bull market and the start of a financial storm. When the Danielcode 59 death cycle bites there is no interest rate or central bank liquidity injection that can save the market.

Markets turn on Danielcode ratios of time and price and when they do, nothing or nobody can change that. Markets do not turn because they are overbought or because some event happens. They turn on a specific time and price because it's in their DNA to turn there and that DNA is ruled by the Danielcode numbers hidden in the old testament. Amazed? You should be.

THE 3RD DAY

Remember I just showed you how NDX was at the 3rd standard deviation of the mean? 3 is a fractal of 6 and 6 days is a DC week ("6 days you shall work and on the 7th day you shall rest").

The number 3 is important all across the Bible and since it's Easter today let me remind you what is written in Luke 24:7

Luke 24: 7 "The Son of Man must be delivered over to the hands of sinners, be crucified and on the third day be raised again."

Well folks, take a look at the next long term 24 day chart of NDX. The 59 time cycle comes from the 59.3 Danielcode number and that number comes from 1335/45 which is 29.666 half of 59.333. If you multiply that number by 3 you get exactly 178. Well in early April we were 178 bars away from the 2000 peak in NDX.

Larger Image

And that my friends should get you exited. The Danielcode is the biggest discovery in financial markets ever made. I know that is a big statement but I also know it's true. I do not wish to impress you nor do I care whether you believe me or not. But I know that you cannot deny the charts I just showed you and I hope that is enough information to get your investigative mind stimulated so you can do some digging around on the Danielcode website yourself. There is a ton of information there just waiting to be discovered and I promise you that the believer's mind will be blown away. And remember, markets are ruled by the Danielcode. They always have been, they always will be. Even Isaac Newton knew that there was major knowledge hidden in the book of Daniel.

TORMANTA 6 FINAL

Larger Image

EUROPE IS STILL A SUPERPOWER

And it's going to remain one for decades to come.

BY ANDREW MORAVCSIK.

Sixty years after the Treaty of Rome, many view Europe as a spent force in global politics. Conventional wisdom states that world politics today is unipolar, with the United States as the sole superpower. Or perhaps it is multipolar, with China, India, and the rest rising to challenge Western powers. Either way, Europe’s role is secondary — and declining. The European Union, it is said, is too weak to avoid withering away in the face of Russian subversion, mass migration, right-wing revolt, British plans to leave, slow growth, and anemic defense spending.

Of course, it’s easy to spot signs of disarray. Modern Europe is messy, and its institutions and policies are imperfect. Some of the threats facing the EU are real: slow growth and austerity, for instance, within the eurozone. Others, like rising right-wing nationalism and migration, are less so, for reasons I will discuss at the conclusion.

Yet amid all the hyperbole and hysteria, a basic point gets missed. Europe today is a genuine superpower and will likely remain one for decades to come. By most objective measures, it either rivals or surpasses the United States and China in its ability to project a full spectrum of global military, economic, and soft power. Europe consistently deploys military troops within and beyond its immediate neighborhood. It manipulates economic power with a skill and success unmatched by any other country or region. And its ability to employ “soft power” to persuade other countries to change their behavior is unique.

If a superpower is a political entity that can consistently project military, economic, and soft power transcontinentally with a reasonable chance of success, Europe surely qualifies. Its power, moreover, is likely to remain entrenched for at least another generation, regardless of the outcome of current European crises. In sum, Europe is the “invisible superpower” in contemporary world politics.

HERE’S WHY.

Flags of EU member states hang inside the Council of the European Union's Lex building on Feb. 18, 2016 in Brussels. (Photo credit: DAN KITWOOD/Getty Images)

WHY EUROPE SHOULD BE VIEWED AS A SINGLE ACTOR

Before turning to Europe’s specific military, economic, and soft power assets, let’s dismiss the nearly universal belief that Europe is too decentralized to act as a superpower. Europe is not a sovereign state. Yet in practice, it generally acts as a single force in world politics.

We ignore European unity at our peril. Most observers analyze Europe as 28 separate countries — even though doing so generates geopolitical nonsense. To see why, consider one recent example: Russia’s foreign-policy options after its invasion of Ukraine triggered Western sanctions. Many predicted that China’s rising economic weight meant the Kremlin would surely turn to Beijing. In July 2015, leading newspapers across Eurasia ran the same story (originally from Agence France-Presse) reporting that “China has emerged as Russia’s largest trading partner as Moscow turns east, seeking markets in Asia in the face of Western sanctions.”

Yet Russian President Vladimir Putin quickly discovered the futility of a Russian pivot to Asia. While the premise is, strictly speaking, true — China is Russia’s top trading partner — it accounts for only 14 percent of Russia’s trade. Just three European countries combined — Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands — account for more than 20 percent, and Europe as a whole for over half. No realistic increase in trade with China could offset European dominance.

DIRECTION OF RUSSIAN TRADE (2015)

Treating Europe as disunited was geopolitically naive. Even though EU law imposes no legal obligation to implement sanctions, Europe acted — and paid more than 90 percent of the costs of the Western policy response to Russia. European power and unity are the glue that has held together this Western policy for the past two years.

This is only one example of how, despite its fragmentation, Europe effectively projects power in those areas that count most for global influence. Certainly, European governments often disagree among themselves, sometimes vociferously and in public. Yet policy coordination, both formal and informal, permits European governments to act as a unit to influence the outside world. Three modes of European coordination are critical: common EU policies, coordination, and tacit policy convergence.

First, EU member states often share a formal mandate to cooperate. Governments are generally obligated legally to act together in the name of the European Union on trade, regulatory, environmental, monetary, neighborhood policy, development, EU enlargement, the free movement of people, and border controls. When serious disagreements arise, countries often resolve them through constructive abstention, in which some governments set aside their own concerns and permit the EU to exercise its collective power in areas of greatest importance to others.

Second, even when EU law does not formally mandate uniformity, European governments often form “coalitions of the willing.” After 60 years, Europe has entrenched a continental network of informal norms, procedures, and institutions that quietly encourage policy coordination. European foreign and defense policies illustrate how this system of voluntary solidarity works. Member states take foreign-policy positions in common, which can be implemented by the EU high representative and common diplomatic service, or by coalitions of national governments acting on their own. EU governments coordinate national positions in international organizations, including the United Nations. Not all governments need to participate for these actions to be successful. Again, constructive abstention permits governments to signal disagreement in principle with decisions that nonetheless go forward in practice — as occurred, for example, in recent decisions involving the former Yugoslavia and Libya, or recent efforts to dampen migration across the Mediterranean.

This coordination extends to collective European military operations. While no formal mandate exists, missions often lack a formal EU imprimatur and involvement limited to those who wish to participate. Yet, in one form or another, European governments have launched dozens of joint military operations since the end of the Cold War. Impasses like the 2003 Iraq War, when European governments so strongly disagree that they pursue opposing policies on a prominent global issue, are extremely rare.

Third, even when the EU neither mandates nor coordinates a policy response, the convergent national laws, strategies, and interests of European states more often than not generate compatible and mutually reinforcing policies. European governments have overlapping international institutional memberships and legal obligations. Almost all are NATO members, which means they conduct common planning and training and accept collective defense obligations. They adhere to the same treaties governing asylum, human rights, the environment, development, and many forms of U.N. cooperation. All are friendly with the United States. They share national embassies. In the soft-power realm, the ability of Europeans to educate foreign students, set global constitutional norms, and garner a worldwide following for athletic achievements contribute to a common European influence in the world — even if the EU explicitly coordinates little of it.

At a more fundamental level, all European countries are democratic and economically interdependent, and they share largely uncontested (indeed, often invisible) borders. Hence they coexist without posing any mortal threat to one another. With the highly unlikely exception of a Russian attack on NATO, they face no such immediate security threats from other great powers, either. This relatively benign environment affords Europeans the luxury of focusing their geopolitical influence on other, more distant matters. This differs strikingly from the situation of, say, China, which must prepare for potential military conflict with almost all of its regional neighbors — Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India, Russia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and other South and Southeast Asian states, not to mention the United States — and keep its army in reserve to maintain domestic order.

For these reasons, we should recognize Europe as a single superpower in projecting military, economic, or soft power — whether or not it acts formally as one.

British soldiers are silhouetted against the sky as they provide security for a meeting with the Afghan National Police in Lashkar Gah on May 17, 2006. (Photo credit: JOHN D MCHUGH/AFP/Getty Images)

EUROPE’S MILITARY MIGHT

Let’s begin with “hard” military power. While Europe’s ability to project coercive force to compel others to acquiesce to political demands does not match that of the United States, it is more active and capable than any other global power. The oft-repeated phrase that “Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus” is a great sound bite but a misleading policy analysis.

The conventional starting point for measuring military capability is the money each country spends on defense. On this score, the United States, which accounts for more than 40 percent of global military spending, heads the list. After that, most analysts list China, with the second-highest national spending and more than 2 million active duty soldiers, followed by Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, India, Japan, France, Germany, and South Korea.

Here again the failure to aggregate Europe clouds our geopolitical vision. If we unify European military activities, it comes in second. European military spending accounts for 15 to 16 percent of the global total. China runs third, with under 10 percent, and Russia spends less than 7 percent, less than half as much as Europe.

At current growth rates, China’s annual military spending (or perhaps that of other rising powers) will not surpass that of Europe for at least a few decades, and the United States for one or two generations — even on the optimistic assumption that Chinese growth continues.

To be sure, this isn’t quite a one-to-one comparison, since Europe’s militaries make their spending decisions separately. Some inefficiencies result when, say, France and Italy separately purchase and maintain their own aircraft carriers. Yet studies suggest that efficiency losses due to decentralized production and procurement — a problem that also bedevils the United States and China, with their domestic interservice rivalries and political pork-barreling — is much smaller than one might think. The most promising area for reform (consolidation of national defense industries) generates no more than 7 percent (about 14 billion euros) savings. This is real money, but too small a number to significantly alter Europe’s relative international standing. Moreover, the “bang for the buck” of the weapons Europe procures remains competitive, as evidenced by the fact that it consistently ranks as the world’s No. 1 arms exporter, outstripping even the United States and Russia.

Yet even Europe’s advantage in annual defense spending understates the entrenched military advantages that it (like the United States) enjoys over any rising power. Usable military capability is not a simple function of defense spending in a given year, but investment in stocks of defense technology, materiel, training, and experience sustained over generations. The average age of equipment in the U.S. military varies from 10 to 25 years, and the life cycle of a fighter like the F-18, introduced just after the Vietnam War, will be nearly a century.

For China to challenge Europe or the United States on an equal basis, Beijing would need to outspend the West not for one year, but for decades — something that delays the projected point where (at current trends) it would surpass the West close to the end of the 21st century.

All scenarios whereby China (or another rising power) advances more quickly require increases in military spending of at least 15 percent per year. That in turn means that China must either triple its economic growth rate (unlikely) or increase military spending tenfold as a percentage of the gross domestic product (a strategy that, Chinese leaders are well aware, bankrupted the Soviet Union).

A final reason for Euro-optimism is that Europe maintains enduring alliances. The United States and Europe are irrevocably — yes, even in the age of President Donald Trump, as recent reassuring words to NATO partners by Vice President Mike Pence and cabinet officers demonstrate — allied with one another and with 28 other NATO countries. This bloc commands almost 60 percent of global military spending. Europe, like the United States, maintains security partnerships and bases across the globe, as well as close relations with dozens of countries around the world.

By contrast, Russia and China can call on few allies. Beijing offers modest military training and some assistance to Cambodia, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Syria, and a few African countries; maintains a security partnership with Pakistan; and has only one ally: North Korea.

These advantages are not just theoretical. European militaries actually do more in the world than those of any country except the United States. Only Europe and the United States have deployed tens of thousands of combat troops outside of home countries almost continuously since the end of the Cold War. During the past decade, European deployments have averaged 107,000 soldiers per year on land, plus a considerable naval presence. By contrast, China has deployed almost no combat soldiers abroad, and India has done so only within U.N. missions.

Recent Russian activities have been limited to brief forays in neighboring parts of the former Soviet Union and air and naval support for its sole remaining Middle Eastern ally.

Europeans do not just participate; they lead. They have headed military operations in Macedonia, Bosnia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad, Somalia, and Mali. They have led naval operations off the Horn of Africa and in the Mediterranean. They have conducted support or monitoring missions in Sudan, South Sudan, Guinea-Bissau, Libya, Indonesia, Iraq, Moldova, Kosovo, Georgia, Niger, the Palestinian territories, Ukraine, and the Baltic States. They have led U.N. missions, including in Lebanon. They have participated in a vital way to U.S.-led missions, including Iraq and Afghanistan. In the latter, more than 25 percent of the fatalities suffered by Western forces were Europeans from 23 countries. The world, and the burden on the United States, would be quite different without all this European activity.

Despite their powerful military, many claim that Europeans could do more in the world if only their governments would spend more on defense — perhaps the 2 percent of the GDP that NATO leaders promised a few years ago. Yet little evidence suggests that more men and materiel — or greater centralization in EU institutions — would generate much more or better European military activity. While Europe did suffer the indignity of asking the United States to resupply it in Libya, it is difficult to see why, as many argue, the Europeans should develop more military capacity across the board. The need for resupply did not affect the outcome of Libya, and it is unlikely to do so elsewhere either, since the United States and Europe have agreed on every military intervention but one since the early 1990s. (The second Iraq War was a lonely exception.) One is hard-pressed to think of any recent case in which a significant group of European states (let alone a majority) desired to launch a strong military or diplomatic mission, but failed to do so for lack of military might. .

EUROPE’S PREEMINENT ECONOMIC CLOUT

Europe possesses impressive military assets, yet the main drivers of its global influence lie elsewhere. Europeans tend to be skeptical about using military force in wars of choice, and have therefore chosen to specialize in nonmilitary tools of statecraft. Their capacities here often exceed those of the United States.

Europe’s comparative advantage in civilian power is as vital to global peace and security as U.S. military might. To be sure, a century ago military might was widely viewed as the most essential of global power resources. Yet today it is rarely decisive. It is simply too expensive and uncertain, relative to the potential gains. No direct conflict has occurred among “great powers” since the Korean War. Smaller wars are also steadily becoming both less common and less costly. When they get involved, great powers tend to lose more than they win. Syria is troubling, but it is an exception to a much larger trend away from interstate war.

Countries now typically find nonmilitary means to manage the most important global problems: not just territorial issues, but economic interdependence, development, environmental degradation, global health, human rights, migration, and even terrorism and crime. Among the most important nonmilitary capabilities is economic power. It is hard to see military power playing much of a role in dealing with most such problems. Though Europe maintains a robust military, it makes sense for it to specialize in a type of power that the United States cannot project.

One European specialty is economic power projection. To induce political concessions, European countries manipulate access to their markets, condition economic assistance and exchange, and exploit regulatory and institutional dominance. Thus, a basic source of European economic power is the raw size of its economy.

The conventional wisdom again misleads us. According to a recent poll of citizens in 40 countries, almost everyone in the world believes either that China is already the world’s dominant economy, or that the United States still maintains primacy. Only 5 percent think of the EU as a “leading economic power.” Yet those 5 percent have a point. By the simplest measure of economic power, nominal GDP, the EU is nearly the same size as the United States and 63 percent larger than China.

This may surprise those who have read widespread reports that China now has the world’s largest GDP. Such analyses are deceptive because they employ “purchasing power parity” (PPP), a statistical measure developed by international development agencies to measure individual poverty and wealth in poorer economies where services and labor are cheap. PPP-based gross national product statistics deliberately inflate developing country income in ways that exaggerate the international value of exports and imports, high technology, modern weapons systems, foreign aid, and most other elements of international economic influence. The more appropriate standard for measuring a country’s aggregate economic clout is its nominal GDP. By this measure, China will not surpass the EU or the United States for decades.

Recent newspaper headlines about the dominance of China and the United States are misleading because they, again, disaggregate Europe into 28 individual countries, rather than treating it as unified. The EU is, in fact, the world’s second-largest economy. Even more importantly, it is the world’s largest trader of goods and services.

Since exports can be a source of vulnerability as well as strength, a more focused measure of trade power is dependence on foreign markets. The more trade dependent a country is, the less powerful it is. Europe is slightly more trade dependent than the United States but far less than China.

What about recent increases in Chinese foreign direct investment that have triggered so much media attention? As it turns out, Europe remains the world’s leading foreign investor.

To be sure, if you sell natural resources in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, or Australia, Chinese investment is a big deal. Otherwise, we should remember that most global investment still takes place among developed countries, where China’s role remains modest.

Yet even this underestimates Europe, because effective economic power depends not just on the relative size of its economy but on average per capita income. The poorer its citizens, the fewer resources governments can extract from them. In poorer countries, development is often the primary imperative, foreign-policy spending a luxury, and the overall level of autonomous technological sophistication low. While the aggregate income of China ranks in the top three, its per capita income ranks 74th (between Saint Lucia and Gabon). Azar Gat, an Israeli scholar, estimates that developed governments like those in Europe extract three or four times as much for foreign-policy purposes as the governments of developing countries like China. One example is the ability to tax. Revenue as a percentage of GDP is almost twice as high in the EU as in China.

Europe does not hesitate to exploit its preeminent economic position. EU enlargement —driven largely by perceptions of economic advantage — has been in recent decades the most cost-effective political tool of influence in the hands of any Western country. Over 60 years, the EU has expanded from six to 28 members, encouraging countries to adopt democratic, legal, and market reforms along the way. Though enlargement is now more difficult politically, it continues in the western Balkans.

Europe further leverages its regional market power through a “neighborhood policy” of bilateral agreements with nearby countries from Morocco to Moldova. It supports the World Trade Organization and imposes conditionality on its preferential trade agreements. Inward visa-free travel and migration are important quid pro quos in negotiations with neighbors. To the chagrin of U.S. and Chinese companies, Europe dominates global regulation, forcing its trading partners to adopt relatively high European product standards — a phenomenon Columbia Law professor Anu Bradford calls a hegemonic “Brussels effect.”

Other European economic instruments are less visible but no less important. One example is foreign aid. Europe provides 69 percent of global official development assistance (ODA), compared with 21 percent for the United States and far less for China. Europe, like the United States, offers the bulk of its total aid in the form of grants, whereas China tends to provide not ODA but export credits and government loans — financial flows that must be repaid and are thus less valuable to recipients. Yet even if you include both, Europe’s financial presence dominates that of the United States and China.

European foreign aid has played a decisive role in promoting Western strategic objectives. For example, Europe’s 10 billion to 15 billion euros of annual economic aid and the promise of freer trade and energy arrangements constitute 90 percent of Western aid and trade with Ukraine. Ukraine remains troubled, yet without Europe’s economic commitment the government in Kiev would have surely gone bankrupt and fallen back into the Russian geopolitical sphere.

Another example of a uniquely effective instrument of European economic power is the imposition of economic sanctions. Ukraine again illustrates the point. As with aid and trade policies, 90 percent of the cost of recent Western sanctions against Russia falls on Europe. This reflects Europe’s unique clout as the largest trading partner not just of many countries in the former Soviet Union, but nearly every country in the Middle East and Africa. It is hard to imagine sanctions working anywhere in the world without Europe’s active participation. The United States, by contrast, hardly trades with most of these countries, and thus it lacks the capacity to levy effective sanctions on its own. For example, Washington sanctioned Tehran continuously for 35 years with little effect. After Europe signed on to tough sanctions in 2013, Iran agreed to a nuclear deal within two years.