ARTICULOS EXTERNOS CON ANALISIS ADECUADO

FINANCIAL; ECONOMIST; WALL STREET BEST MINDS; GROSS Y FRIEDMAN

Por:Dennis Falvy

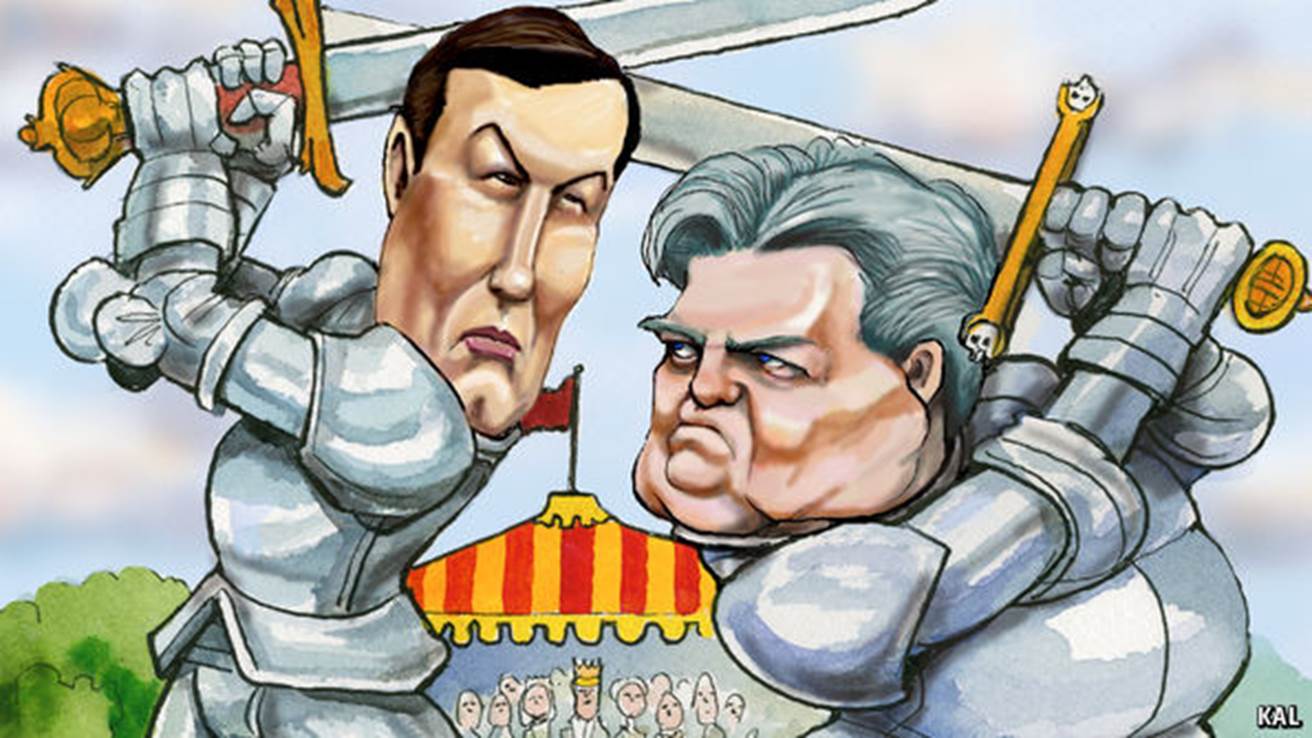

HOW TO MAKE SENSE OF TRUMP V TRUMPISM

The struggle between the Bannon and Kushner factions is about more than dynasty

BY : :THE ECONOMIST

Proximity to power does not make Washington, DC, a kindly place. Like medieval peasants watching knights joust, the yokels and churls of the political village—lobbyists, consultants or (hold your nose) journalists—may nod and gawp at the mighty, but their hope is to see one grandee thwack another into the mud.

These are, therefore, heady times in the nation’s capital. Two powerful men, Stephen Bannon, chief strategist to President Donald Trump, and Jared Kushner, a senior adviser, have been jousting for weeks, exchanging sword-swipes and lance-blows via leaks and briefings in the press. Still more blissfully for spectators, Mr Kushner is the president’s son-in-law: the boyish, dashing heir to a family of property tycoons and Democratic donors, and husband to Mr Trump’s daughter and trusted counsellor, Ivanka. His rival, Mr Bannon, is older and angrier: a grizzled champion of America First nationalism.

This White House tourney is usually presented as a clash of partisan ideology or as a human melodrama. Some complaints from the Kushner camp certainly ring with dynastic alarm. The ultimate argument against Mr Bannon, one unnamed source told the Washington Post, is that his hardline, fire-up-the-faithful brand of politics “isn’t making ‘Dad’ look good”. For their part, Bannonites inside government and their cheerleaders in the conservative media like to paint Mr Kushner as a closet liberal, undercutting Mr Trump’s historic populist victory. Their ire also takes in Ivanka, as well as Gary Cohn, the president’s national economics adviser, and Dina Powell, a deputy national security adviser, both of them veterans of Goldman Sachs, a bank (to complicate matters, Mr Bannon also once worked for Goldman Sachs, but more recently earned notoriety as the rumpled, combative boss of Breitbart, a hard-right news outlet).

When briefing against the Kushner faction, the Bannon camp uses such slurs as “the Democrats”, “the New Yorkers” or “the globalists”. Mr Kushner and his elegantly tailored friends are charged with being squeamish about immigration, too eager to see America play global policeman in Syria and peacemaker in the Middle East, and willing to give a hearing to Democratic experts on such subjects as health policy or climate change. Bannonites, Democrats and pundits have mocked Mr Kushner for the range of his responsibilities. The president’s son-in-law is charged with overseeing everything from Middle East peace to relations with Canada, Mexico and China, and reorganising the federal government using lessons from business.

But to cast these fights as a clash between left and right, or even as palace intrigues, is to miss the whole story. The semi-public combat between Mr Bannon and Mr Kushner rests on an argument about something much larger: namely, the purpose of Mr Trump’s presidency itself.

For Mr Bannon, the point of winning the 2016 election was to advance a cause, which history may in time call Trumpism. A former naval officer from a blue-collar family in Virginia, he spent years studying theories of how societies collapse. He has made several lurid, doomy films alleging that working families have been sold out by rootless, corrupt elites, who stood by and profited as immigrants flooded in. Other works lamented the collapse of Judaeo-Christian values in the American heartland. Mr Bannon saw before many others on the hard right that Mr Trump might not be a conventional conservative, but still “intuitively” grasped the power of economic populism. On joining the government as the president’s ideologue-in-chief, Mr Bannon pasted specific promises made in Trump campaign speeches on the walls of his West Wing office. Those promises cover everything from border security to global trade and an assault on regulations and the federal agencies that write them, through what Mr Bannon calls the “deconstruction of the administrative state”.

Addressing conservatives in February, the strategist assured them that, whenever establishment types try to lure Mr Trump away from that radical agenda, “He’s like: ‘No, I promised the American people this, and this is the plan we’re going to execute on’.”

During the election Mr Bannon bonded with Mr Kushner in their shared contempt for professional campaign consultants. To hear Mr Kushner describe it, the Trump campaign resembled a disruptive startup, full of tech whizzes with “nontraditional” backgrounds outside politics. Addressing New York business bosses in December, Mr Kushner explained how the campaign exposed him to the anger of Americans who feel ignored by their government. He realised that he lived in a “bubble” of elite opinions about such subjects as immigration or the environment.

“I LIKE STEVE, BUT...”

However, Mr Kushner differs in at least one important way from Mr Bannon. He acts as if the last election was a victory for a man called Trump, not a movement called Trumpism. Shortly after the election Mr Kushner told Forbes magazine that his father-in-law transcends party labels, with policies offering “a blend of what works, and eliminating what doesn’t work.”

Both men entered the White House rooting for Mr Trump to prove critics wrong. But if Mr Trump prospers by breaking every campaign promise, Mr Bannon’s nationalist cause will have been betrayed. The strategist has survived until now by telling Mr Trump he can help him keep those pledges, shoring up his most loyal bases of support. Yet over time, history suggests that seeking to bind Mr Trump with his own words is a losing gambit.

The logic of Mr Kushner’s family first pragmatism is simpler: Americans will thank Mr Trump if his policies improve their lives. For now both men offer the president possible paths to success. At some point their visions will prove incompatible—hence recent rumours, fuelled by Mr Trump, that Mr Bannon may be sacked. The prize being fought over is the president’s legacy. That is a contest not everyone can survive.

DEALING WITH AMERICA’S TRADE FOLLIES

Its policies will fail to reduce deficits — for which foreigners will be blamed

BY: MARTIN WOLF (FINANCIAL TIMES)

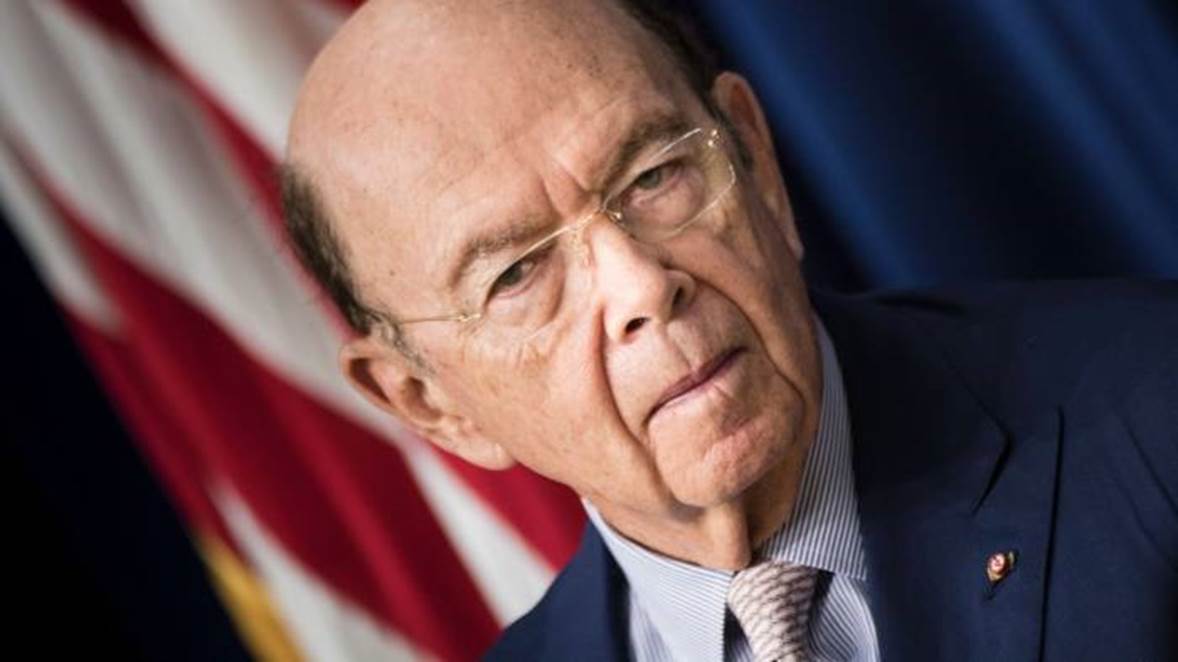

Wilbur Ross, US secretary of commerce © AFP

How are trade partners to respond when US policymakers talk nonsense? That is the situation in which Europeans, Japanese and South Koreans now find themselves. The words of Wilbur Ross, US commerce secretary, and the man who Donald Trump trusts most on trade policy, show one can be a billionaire and yet not understand how the economy works, just as one can be an athlete and not understand physiology.

Objecting to warnings of protectionism from Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Mr Ross told the Financial Times that “we are the least protectionist of the major areas. We are far less protectionist than Europe. We are far less protectionist than Japan. We are far less protectionist than China.”

He added: “We also have trade deficits with all three of those places. So they talk free trade. But in fact what they practice is protectionism. And every time we do anything to defend ourselves, even against the puny obligations that they have, they call that protectionism. It’s rubbish.”

It is what Mr Ross says that is rubbish. A trade deficit is not proof that a country is open to trade. It is proof that it is spending more than its income or investing more than it saves. This is not just a theoretical point. Solid evidence supports it.

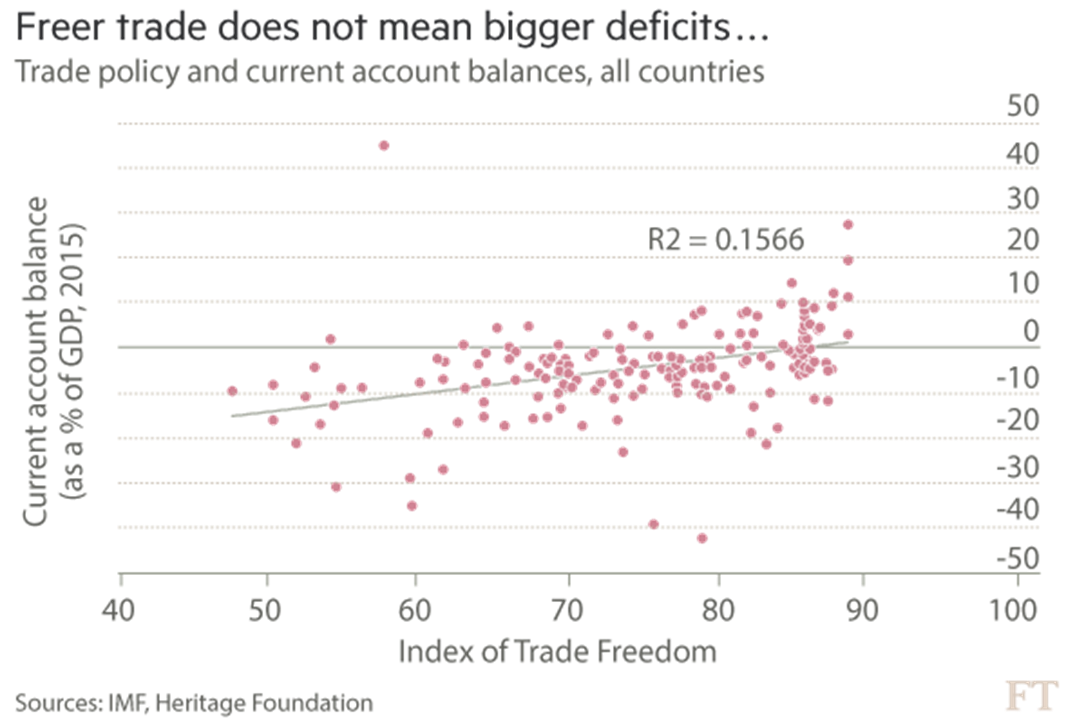

The Heritage Foundation, no less, provides an annual Index of Economic Freedom, which includes “trade freedom”. The think-tank, which prides itself on commanding influence in the Trump administration, derives the latter from data on trade-weighted tariffs and non-tariff barriers. The US, it shows, has far from the most liberal trade policies.

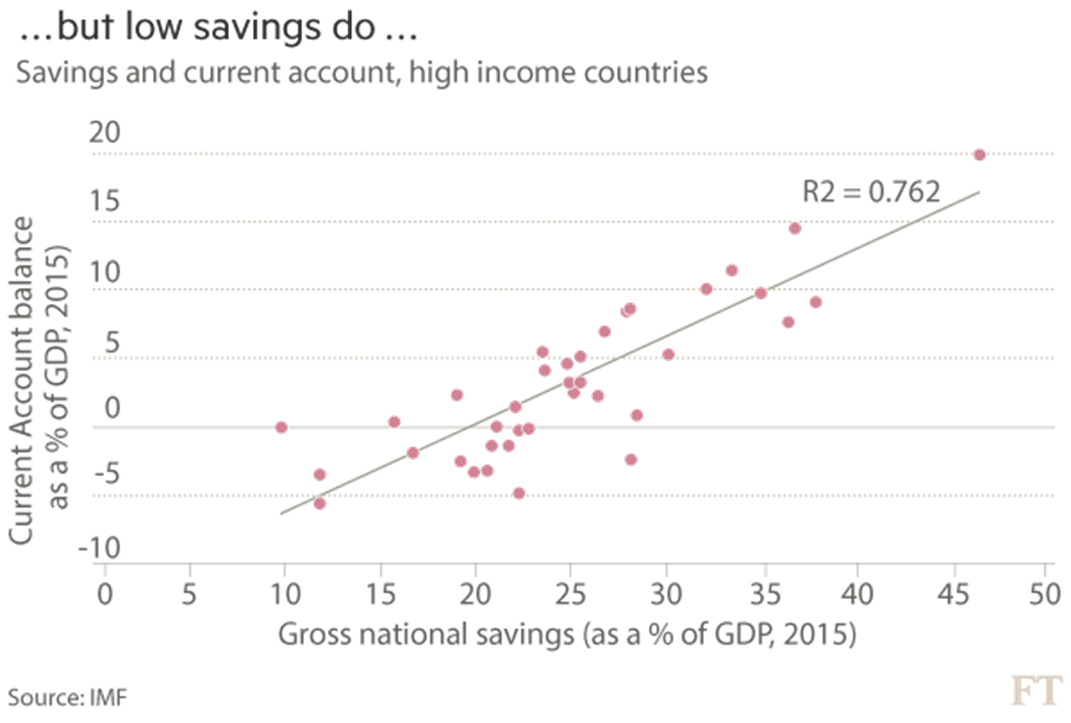

These measures of trade freedom can be combined with data on current account balances, adjusted for the size of economies. (On this basis, the US deficit was 98th biggest out of 177 countries.) Just as theory predicts, no significant relationship exists between trade freedom and deficits. To the extent there is one, it is in the opposite direction: there is a weak tendency for liberal traders to run larger surpluses.

The idea that protection will reduce trade deficits does make intuitive sense. It is wrong, however, because the economy does not consist of isolated markEts: everything is related to everything else. Taxes on imports are also taxes on exports. If one imposes protection against imports, one pulls resources out of production for export. To put the point in other words, exports are just a way of supplying imports. If a country imports less, because of protection, the incentive to produce exports will, other things being equal, also fall. The mechanism through which this is likely to happen, in the case of the US, will be a rise in the dollar, as the demand for imports falls. Thus, protection reduces ratios of trade to gross domestic product (making economies more closed), not trade deficits.

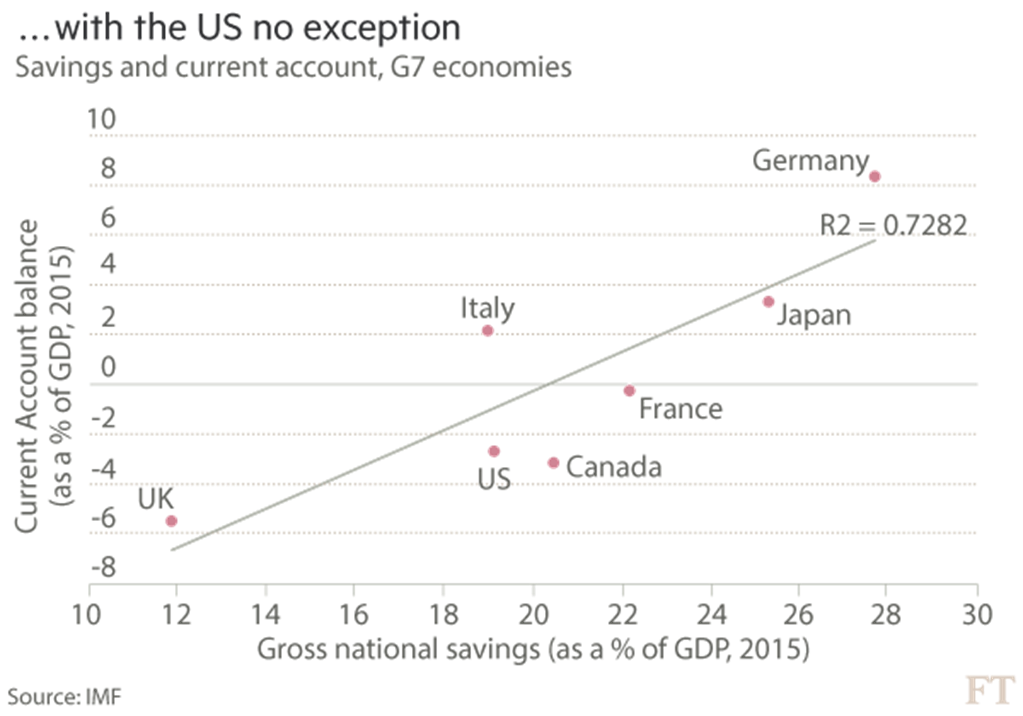

Now compare the savings rates of high-income economies with their current account balances (again relative to GDP). Just as one would expect, differences in national savings rates are powerful predictors of current account balances. If we look at high-income countries alone, we find that the US is not exceptional in any way. It is a relatively low-saving country that, largely as a result, has persistently run a current account deficit.

This has allowed the US to invest more than it saves. If it wishes to reduce its external deficits, it must either lower investment (evidently, a bad idea) or raise savings. If it wishes to do the latter, the obvious start would be not to slash taxes, as planned, but raise them, instead.

Mr Ross’s misunderstandings of the economics of trade are far from harmless follies. The administration’s fiscal policies seem sure to increase the US external deficit, for which foreigners will be blamed. Its trade policies will fail to reduce US trade deficits, for which foreigners will again be blamed. The US will propose the ludicrous objective of bilateral trade balancing in a world in which commerce itself is multilateral. This too will fail, for which foreigners will be also blamed. In all, the administration could demolish the open trading system simply because it is clueless.

The trading system has been the basis of post-second world war prosperity. This period has in turn been the most prosperous for humanity in history. An excellent recent paper from the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization lays out both what is at stake and needs to be done to spread the gains from trade more widely.

In particular, it demonstrates that creating a safety net for affected workers and communities, combined with policies to support adjustment to change, is effective. Yet that is precisely what the Republicans intend to weaken. Alas, that makes protection the only policy on offer to those adversely affected by economic changes, including imports.

What is frightening about the trade agenda of the administration is that it manages to be both irrelevant and damaging. A relevant agenda would focus on the imbalances in savings and investment across the world economy. A beneficial agenda would focus on combining the necessary adjustment to economic change, of which trade is a relatively small part, with widening shares in the gains and assistance with adjustment. It would also recognise that trade has been one of the engines of economic dynamism. What is most worrying about trade has been the slowdown in its growth. That, the World Bank suggests, may be one reason for the productivity slowdown.

So how should trade partners respond to US demands? They need to accept the significance of macroeconomic imbalances. They need to make concessions that increase trade, without damaging the global economy. They need to argue the case for multilateral liberalisation. They need to do whatever they can to protect the principle of trade rules that bind both strong and the weak. Above all, they need to be patient. The US should not be governed forever by those who have so little understanding of what is at stake.

WALL STREET'S BEST MINDS

BILL GROSS: STOCKS REST ON FAULTY FOUNDATION

Equities “are priced for too much hope,” junk bonds “for too much growth,” writes the fund manager.

BY WILLIAM H. GROSS

BILL GROSS, CO-FOUNDER OF PIMCO TO COME

Here’s an investment brain teaser: Can the Trump Agenda recreate 3% annual growth in the U.S. economy?

Well, now, that is the investment question of the hour/day/decade and its conclusion, unlike romance on a desert island, will determine the level of asset prices across the investment spectrum.

Three percent growth leads to a levered rate of corporate revenue/profit increases and a significantly higher price/earnings ratio, all else equal. Three percent growth also sends a green light/all clear signal to high yield bonds and other risk assets that are leveraged and growth dependent. It may also, although not necessarily, lead to higher real interest rates and a future bond bear market. So what’s the answer?

Well, growth is productivity dependent, and the experts are in a tizzy trying to explain why productivity in the last five years has averaged only 0.5% versus a prior pre-Lehman “old normal” of 2%-plus. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, speaking on April 10, said that no one really knows the answer, which was her way of saying that the past five years’ experience has been three standard deviations outside of the Fed’s model. But others, such as Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon, have long argued that lower productivity may now be a function of having picked all of the “low hanging fruit” such as electrification and other gains from 20th century technology. Then there is the obvious connection between recent years’ low levels of private sector investment, which perhaps begs another as to why that is so low. Optimists claim that the future benefit of smartphones and medical technology have yet to have an impact and that eventually – much like the introduction of the automobile – they will lead to a resumption of historical trends.

But in a detailed report by the IMF, their economists argue that the current trend is an offspring of the financial crisis. Slowing business investment/trade and an ongoing level of low to negative interest rates have resulted in a misallocation of capital to low risk projects and a slowdown in small business creation.

Longer term secular demographic factors such as an aging population also play a significant part since older consumers consume less of almost everything except health care. So Chair Yellen may just be sticking to her old models and her educated but “common sense” deficient staff that claims that no one really knows the answer. She may need to “tease” her brain that is so focused on historical but dated economic models. There may be answers and solutions that other organizations are coming to grips with.

The same IMF study suggests that unless there is an unforeseen technological breakthrough, productivity growth is unlikely to return to the higher rates of the 1990s for advanced economics or the early 2000s for emerging economics. In other words, their warning speaks to a global productivity slowdown, not just a U.S. based phenomena.

They warn that increasing tariffs and developing restrictions on immigration will only exacerbate the slowdown. Global growth, and of course U.S. growth, will be lower than average, they forecast.

And if so, what are the investment conclusions? Well here’s where a two handed economist might fall back on the conclusion of my six original brainteasers: There is no right or wrong answer. But since I have two hands but have frequently been accused (praised) of not being an economist, I’ll post my own comment.

Equity markets are priced for too much hope, high yield bond markets for too much growth, and all asset prices elevated to artificial levels that only a model driven, historically biased investor would believe could lead to returns resembling the past six years, or the decades predating Lehman. High rates of growth, and the productivity that drives it, are likely distant memories from a bygone era.

If you’re “interested” in investment performance, hopefully you’ll find these conclusions somewhat “interesting.” Now pick up your cellphone and know that the only real way to have one more year of extended life is to feast on blueberries instead of Oreo cookies and to exercise daily instead of heading for your couch and widescreen.

Gross manages the Janus Global Unconstrained Bond fund (JUCTX).

WHAT A WAR WITH NORTH KOREA LOOKS LIKE

None of the options, apart from de-escalation, are attractive.

BY GEORGE FRIEDMAN

In the last week, the possibility of war between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States has increased. It is necessary therefore to consider what such a war might look like. I am using the term war rather than merely American attacks on North Korean nuclear and missile program facilities because we have to consider the possibility of North Korea’s response and a more extended conflicto.

Such a war would be based on North Korea’s decision to move its nuclear program to a stage where the U.S. and other countries conclude it is possible that North Korea is close to having a deliverable nuclear weapon. Given that the North Koreans could not survive a nuclear exchange, it is hard to understand why they would have moved their program to this point. The obvious reason for having a nuclear program is to use it as a bargaining tool. The reason for having a nuclear weapon would be as a deterrent to a foreign power seeking regime change in North Korea. The most dangerous period for North Korea is when it is close to having a weapon but does not yet have it. That is the period when an attack by an external force is more likely. It is the period before North Korea could counterattack. Pyongyang’s decision to deliberately send signals that it has a nuclear weapon increases the urgency of an attack. Its decision is odd, even if it already has one or two nuclear weapons.

.