DIVERSOS CASOS DE NIVEL INTERNACIONAL

TODOS ELLOS DEBIDAMENTE PRESENTADOS Y CON EL DEBIDO ANALISIS

Por:Dennis Falvy

GROWING OUT OF POPULISM?

By : Kenneth Rogoff.

CAMBRIDGE – After nine dreary years of downgrading their GDP forecasts, macroeconomic policymakers around the world are shaking their heads in disbelief: Despite a populist-propelled wave of political tumult, global growth is actually set to outperform expectations in 2017.

It’s not just American exceptionalism. Although US growth is very strong, Europe has been outperforming expectations by more. There is even happy news for emerging markets, which are still bracing for US Federal Reserve interest-rate hikes but have gained a better backdrop against which to adjust.

The broad story behind the global reflation is easy enough to understand. Deep, systemic financial crises lead to deep, prolonged recessions. As Carmen Reinhart and I predicted a decade ago (and as numerous other scholars have since corroborated using our data), periods of 6-8 years of very slow growth are not at all unusual in such circumstances. True, many problems remain, including weak banks in Europe, over-leveraged local governments in China, and needlessly complicated financial regulation in the United States. Nonetheless, the seeds of a sustained period of more solid growth have been planted.

But will the populist tide surging across the advanced economies drown the accelerating recovery?

Or will the recovery stifle leaders who confidently espouse seductively simple solutions to genuinely complex problems?

With the International Monetary Fund/World Bank meetings coming up later this month in Washington, DC, leading central bankers and finance ministers will have ringside seats at Ground Zero. Who can doubt that US President Donald Trump will make a Twitter punching bag out of any of them who dares criticize his administration’s planned retreat from open trade and leadership in multilateral financial institutions?

Before then, Trump will host Chinese President Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago, his “winter White House.”

It is hard to overstate how much rides on the Sino-US relationship, and how damaging it would be if the two sides could not find a way to work together constructively. The Trump administration believes that it has the bargaining tools to recalibrate the relationship to America’s advantage, including a tariff on Chinese imports or even selectively defaulting on the more than $1 trillion the US owes to China. But a tariff would eventually be overturned by the World Trade Organization, and a default on US debt would be even more reckless.

If Trump can persuade China to open up its economy more to US exports, and to help rein in North Korea, he will have achieved something.

But if his plan is for the US to retreat unilaterally from global trade, the outcome is likely to hurt many US workers for the benefit of a few.

The threat to globalism seems to have waned in Europe, with populist candidates having lost elections in Austria, the Netherlands, and now Germany. But a populist turn in upcoming elections in either France or Italy could still tear apart the European Union, causing massive collateral damage to the rest of the world.

French Presidential candidate Marine Le Pen wants to kill off the EU because, she says, “the people of Europe do not want it anymore.” And while opinion polls have the pro-EU Emmanuel Macron beating Le Pen decisively in the election’s second-round runoff on May 7, it is hard to be confident in the outcome of a two-person race, especially given Russian President Vladimir Putin’s support for Le Pen. Given the unpredictability of an angry electorate, and Russia’s proven capacity to manipulate news and social media, it would be folly to think that Macron is a lock.

Italy’s election is not for another year, but the situation is even worse. There, populist candidate Beppe Grillo is leading polls and is expected to pull in about a third of the popular vote. Like Le Pen, Grillo wants to pull the plug on the euro. And, while it is hard to imagine a more chaotic event for the global economy, it is also hard to know the way forward for Italy, where per capita income has actually fallen slightly during the euro era. With flat population growth and swelling debt (over 140% of GDP), Italy’s economic prospects appear bleak.

Though most economists still think exiting the euro would be profoundly self-destructive, a growing number have come to believe that the euro will never work for Italy, and that the sooner it leaves the better.

Many emerging-market countries are dealing with populists of their own, or in the case of Poland, Hungary, and Turkey, with populists who have already turned into autocrats. Fortunately, a patient Fed, a resilient (for now) China, and a growing Europe and US will help most emerging economies.

The outlook for global growth is improving, and, with sensible policies, the next several years could be quite a bit better than the last – certainly for advanced economies, and perhaps for most others as well. But populism remains a wildcard, and only if growth picks up fast enough is it likely to be kept out of play.

A FISCAL REALITY TEST FOR US REPUBLICANS

By: NOURIEL ROUBINI

NEW YORK – US President Donald Trump’s first major legislative goal – to “repeal and replace” the 2010 Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) – has already imploded, owing to Trump and congressional Republicans’ naiveté about the complexities of health-care reform.

Their attempt to replace an imperfect but popular law with a pseudo-reform that would deprive more than 24 million Americans of basic health care was bound to fail – or sink Republican members of Congress in the 2018 mid-term elections if it had passed.

Now, Trump and congressional Republicans are pursuing tax reform – starting with corporate taxes and then moving on to personal income taxes – as if this will be any easier. It won’t be, not least because the Republicans’ initial proposals would add trillions of dollars to budget deficits, and funnel over 99% of the benefits to the top 1% of the income distribution.

A plan offered by Republicans in the US House of Representatives to reduce the corporate-tax rate from 35% to 15%, and to make up for the lost revenues with a border adjustment tax, is dead on arrival. The BAT does not have enough support even among Republicans, and it would violate World Trade Organization rules. The Republicans’ proposed tax cuts would create a $2 trillion revenue shortfall over the next decade, and they cannot plug that hole with revenue savings from their health-care reform plan or with the $1.2 trillion that could have been expected from a BAT.

The Republicans must now choose between passing their tax cuts (and adding $2 trillion to the public debt) and pursuing a much more modest reform. The first scenario is unlikely for three reasons. First, fiscally conservative congressional Republicans will object to a reckless increase in the public debt. Second, congressional budget rules require any tax cut that is not fully financed by other revenues or spending cuts to expire within ten years, so the Republicans’ plan would have only a limited positive impact on the economy.

And, third, if tax cuts and increased military and infrastructure spending push up deficits and the public debt, interest rates will have to rise. This would hinder interest-sensitive spending, such as on housing, and lead to a surge in the US dollar, which could destroy millions of jobs, hitting Trump’s key constituency – white working-class voters – the hardest.

Moreover, if Republicans blow up the debt, markets’ response could crash the US economy.

Owing to this risk, Republicans will have to finance any tax cuts with new revenues, rather than with debt. As a result, their roaring tax-reform lion will most likely be reduced to a squeaking mouse.

Even cutting the corporate tax rate from 35% to 30% would be difficult. Republicans would have to broaden the tax base by forcing entire sectors – such as pharmaceuticals and technology – that currently pay little in taxes to start paying more. And to get the corporate-tax rate below 30%, Republicans would have to impose a large minimum tax on these firms’ foreign profits. This would mark a departure from the current system, in which trillions of dollars in foreign profits remain untaxed unless they are repatriated.

During the presidential campaign, Trump proposed a one-time 10% repatriation-tax “holiday” to encourage American companies to bring their foreign profits back to the United States. But this would deliver only $150-200 billion in new revenues – less than 10% of the $2 trillion fiscal shortfall implied by the Republicans’ plan. In any case, revenues from a repatriation tax should be used to finance infrastructure spending or the creation of an infrastructure bank.

Some congressional Republicans who already know that the BAT is a non-starter are now proposing that the corporate income tax be replaced with a value-added tax that is legal under WTO rules. But this option isn’t likely to go anywhere, either. Republicans themselves have always strongly opposed a VAT, and there is even an anti-VAT Republican caucus in Congress.

The traditional Republican view holds that such an “efficient” tax would be too easy to increase over time, making it harder to “starve the beast” of “wasteful” government spending.

Republicans point to Europe and other parts of the world where a VAT rate started low and gradually increased to double-digit levels, exceeding 20% in many countries.

Democrats, too, have historically opposed a VAT, because it is a highly regressive form of taxation. And while it could be made less regressive by excluding or discounting food and other basic goods, that would only make it less appealing to Republicans. Given this bipartisan opposition, the VAT – like the BAT – is already dead in the water.

It will be even harder to reform personal income taxes. Initial proposals by Trump and the Republican leadership would have cost $5-9 trillion over the next decade, and 75% of the benefits would have gone to the top 1% – a politically suicidal idea. Now, after abandoning their initial plan, Republicans claim they want a revenue-neutral tax cut that includes no reductions for the top 1% of earners.

But that, too, looks like mission impossible. Implementing revenue-neutral tax cuts for almost all income brackets means that Republicans would have to phase out many exemptions and broaden the tax base in ways that are politically untenable. For example, if Republicans eliminated the mortgage-interest deduction for homeowners, the US housing market would crash.

Ultimately, the only sensible way to provide tax relief to middle- and lower-income workers is to raise taxes on the rich. This is a socially progressive populist idea that a pseudo-populist plutocrat like Trump will never accept. So, it looks like Republicans will continue to delude themselves that supply-side, trickle-down tax policies work, in spite of the overwhelming weight of evidence to the contrary.

EYES BIGGER THAN THEIR WALLETS

CONSUMERS AND FIRMS SEE A TRUMP BOOM. MOST FORECASTERS DO NOT (Economic indicators have rarely sent such mixed signals).

By: THE ECONOMIST

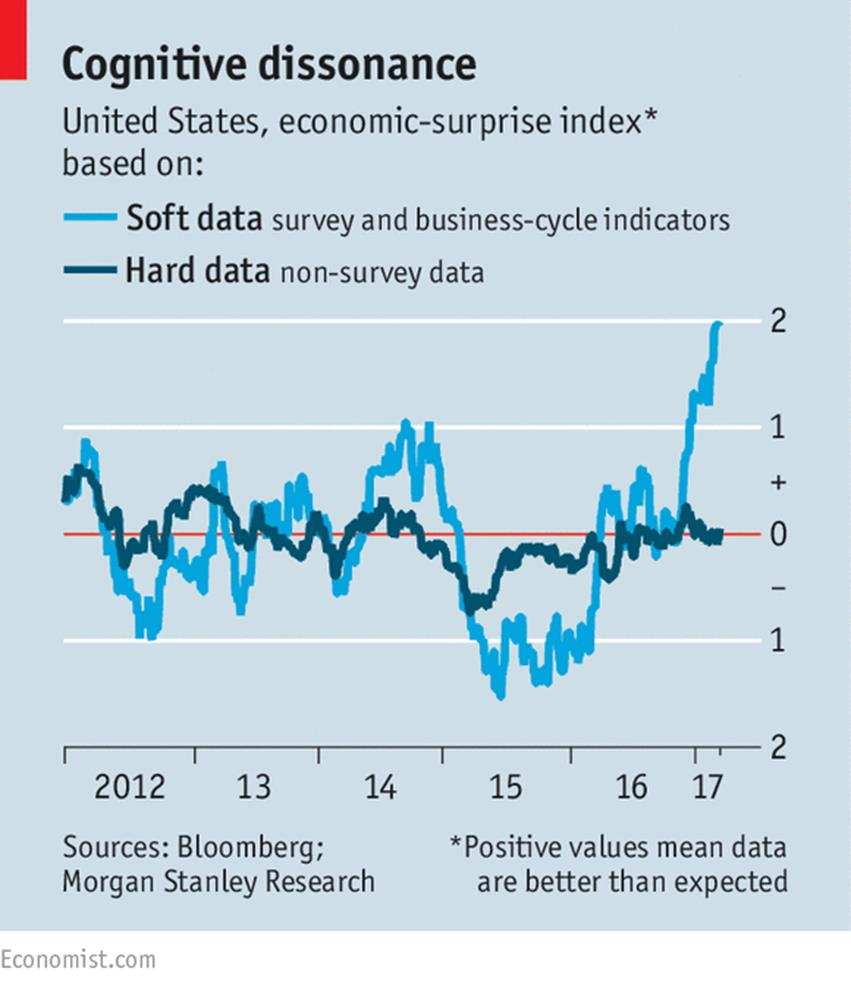

IS AMERICA’S economy booming? Consumers seem to think so. Their confidence, as measured by the Conference Board, a research group, is at its highest since December 2000, when the dotcom bubble had not fully burst. Yet in both January and February this year, personal consumption fell. The signals from firms are no less mixed. Small-business confidence is so high that relying on this alone to predict annualised GDP growth in the first quarter leads to a staggering forecast of 7.1%, according to Goldman Sachs, a bank. Order books are swelling and jobs are plentiful, firms say. Yet industrial production has been flat since December, and banks have slowed business lending dramatically. Americans seem wildly enthusiastic about the economy, but it is not clear why.

The surge in the so-called “soft” economic data, drawn from surveys, began when Donald Trump won the presidential election in November (see chart). It coincided with a boom in the stockmarket, up 10% since then, as investors began to salivate over the prospect of tax cuts and deregulation. Yet the “hard” economic data, which measure actual economic activity, have trundled along much as expected. The disparity has caused growth forecasts to fall out of sync.

As The Economist went to press, a model at the Atlanta Federal Reserve put annualised growth in the year’s first quarter at 1.2%. A competing forecast at the New York Fed put the rate at 2.9%.

.

It is tempting to discount strongly upbeat surveys as driven by politics. Owners of small businesses lean heavily Republican. Consumer confidence is up most among over-55s, who are also likely to have voted for Mr Trump. Most economists’ forecasts are closer to the number from Atlanta than the one from New York. Many of them are mindful of the fact that the economy has often seemed to sag in the first quarter of recent years. An attempt by government statisticians in 2015 to purge the growth data of seasonal factors may not have been a complete success.

Most important, no tax cut or serious deregulation has happened yet. Instead the Republicans have failed to pass a promised health-care reform, which contained large tax cuts for the rich, on their first attempt. (It may soon reappear, but if it does, its passage, especially through the Senate, is far from certain.) There is reason to wonder whether the party is capable of overcoming the political squabbles that will inevitably accompany tax reform.

Yet even if Mr Trump fails to overhaul the tax code completely, few doubt that Congress will pass a simple cut in rates for him to sign. And confidence in the economy may still prove self-fulfilling.

Republicans have long held that replacing Barack Obama’s chilliness towards business with a warm embrace of commerce would lead to an investment boom (on this, they might cite the support of John Maynard Keynes, who wrote that businesses are “pathetically responsive to a kind word”). Although there was no sign of a recovery in investment in the fourth quarter of 2016, sales of capital goods, such as machinery, have picked up a bit this year.

Whether that trend continues will reveal whether confidence is crystallising or dissipating.

Some conservatives, impatient to trigger what they see as an inevitable surge in investment, want tax cuts, whenever they happen, to be backdated to the beginning of 2017.

Retrospective tax changes are rarely a good idea. For the moment, Republicans should be encouraged that two sectors of the economy—housebuilding and manufacturing—have accelerated tangibly. That should please some of Mr Trump’s blue-collar supporters. In February the trade deficit, which Mr Trump views, strangely, as a barometer for economic strength, was 4.5% lower than it was a year ago. A worldwide economic acceleration has helped this trade and manufacturing revival. The dollar has fallen back almost to where it was on the eve of Mr Trump’s election, making American goods cheaper in other countries.

YOU’RE UP, THEN YOU’RE DOWN

What if the surge in confidence proves fleeting? The stockmarket would surely sink. But it is not as if America was in a funk before Mr Trump won in November. The world economy—and financial markets—have been firming up since mid-2016, partly because of fiscal stimulus in China.

America’s recent growth of about 2% has been enough to eat up much of the slack in the economy, as rising inflation shows. Much more productivity-boosting business investment would certainly be welcome, not least because Americans produced barely any more per hour worked in 2016 than they did a year earlier. But Mr Trump’s promise of 3.5-4% growth has never been a realistic goal, because America’s greying workforce imposes a lower speed limit on the economy than in the past.

As that becomes more apparent, the economic elation may subside. If so, those who have been sceptical about soft data as they have heated up should remember to be equally unmoved as they cool down.

WHAT WILL FINALLY BREAK THE MARKET'S LETHARGY?

BY: CLIF DROKE

To most individual traders, there is no bigger buzz kill than a narrow trading range. It takes the wind out of the sails of breakout and momentum traders, and even expert stock pickers have a tough time finding the stocks which are bucking the sideways trend.

Wall Street would much rather see a lively bull market when stocks are roaring and participation is widespread among all classes of investors. But sometimes even a trading range-type market is good enough for the Street , provided stock prices are near all-time highs. For even when prices are making no headway, the aggregate yield on stocks pays enough in dividends to make the lack of action worthwhile.

There are indeed enough listed companies which pay a high enough dividend to make buying and holding in a lackadaisical stock market an attractive proposition. This is one reason for the torpor which currently infuses not only the financial market, but the rest of the country as well.

Why worry when you can sit back and live off the interest? Widespread lethargy breeds a range-bound stock market, but it also contributes to a sluggish economy. As we'll discuss here, there is a reason for the public's lethargy and within that reason lies the solution to the problem.

If you needed proof of the trading range-induced complacency out there right now, the public's response to the U.S. airstrike on Syria is a good example. While there was a modicum of shock and anger, the response to the military action was mostly lethargic. Even the stock market seemed unimpressed enough to rally, which underscores the extent of the public's complacency.

Even Congress is infected with the conservation bug. Even as President Trump touts his ambitious plan to cut taxes, the U.S. House majority leader is pouring water all over that plan by saying Congress will balance any proposed tax cuts by finding ways to increase revenues (read more taxes, but in different areas). Thus the old "paying Peter by robbing Paul" syndrome has infused America's elected leaders, who seem to afraid to risk anything like general prosperity.

One certainly can't fault the President for trying to break the lethargy that has dominated the economy in the last two years. His attempt at lifting the huge burdens imposed on the middle class by reforming Obamacare were spurned by Congress. His latest move appears aimed at stimulating the economy via military conflagration, a tried-and-true (short-term) economic palliative to be sure.

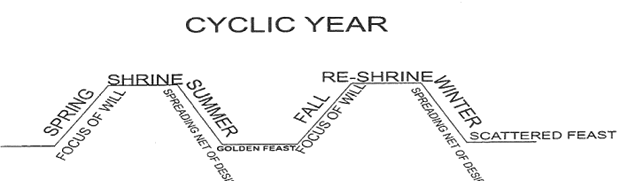

The subdued mood of the market can only be understood in terms of the long-term economic cycle, or K-wave. This cycle is divided into four "seasons" of economic activity over a period encompassing roughly 60 years. Each season approximates to 15 years. The winter season of the cycle was between 2000-2014/15, with the last 60-year cycle bottoming at the end of 2014.

We're now in the early stages of K-wave spring, which should last until about 2029/30.

So if economic spring has sprung, what is keeping the economy from flourishing? The answer to that is best seen in a timely analogy. Even as the Northern hemisphere experiences the early phase of spring in April, there are still lingering signs of the previous winter. While most days are fairly warm, temperatures can still be sometimes chilly and even winter-like. It takes a while for a new season to fully establish itself while the vestiges of the preceding season gradually fade away. In like manner, it will probably take a few years for K-wave spring to become established -- especially given the severity of the K-wave winter season a few years ago.

The question everyone is concerned with is what will it take to finally break the psychological shackles which have held back profligate spending and retail-level investing? The answer to that question can be found in the previous paragraph: the immutable laws of the economic K-wave will eventually lay the foundation for a fundamental change in mass psychology.

At some point in the current K-wave spring season the zeitgeist of contraction and fiscal restraint will give way to expansion and liberality. Until then, expect to see occasional flare-ups of the winter mentality that predominated in the last decade. These flare-ups should become more and more infrequent, however, as the K-wave spring season gradually warms the blood and increases the animal spirits.

When K-wave spring finally hits full bloom, it will bring many economic benefits. There will be a few signs to watch for to let us know that spring has fully arrived. First and foremost, watch for higher yields on U.S. Treasury bonds. There is no surer sign that the long-term economic cycle is accelerating than rising bond yields.

As the new K-wave upward phase progresses we'll also see increasing real estate activity as prospective homebuyers and commercial builders alike look to lock in still-attractive mortgage rates before they get too high. As real estate timer Robert Campbell addressed in his latest newsletter (www.RealEstateTiming.com), U.S. home prices have broken out of a two-year doldrums phase and are rising at their fastest pace since 2014. The momentum of real estate activity is on the upswing.

Finally, look for speculative interest in both stocks and commodities to increase on a large scale.

Risk aversion is a lingering symptom of the contractionist psychology of the K-wave winter season. When K-wave spring blooms in full, however, investment activity will pick up as participants shed their anxieties and trade them in for a more optimistic Outlook.

LIFE AFTER ISLAMIC STATE

'THEY TAUGHT US HOW TO DECAPITATE A PERSON'

BY KATRIN KUNTZ (TEXT) AND ANDY SPYRA (PHOTOS) IN MOSUL, IRAQ.