SOBRE ACONTECIMIENTOS INTERNACIONALES

ATAQUE EN LONDRES; FINANCIAMIENTO FED; EUROPA Y SIRIA

ATAQUE EN LONDRES; FINANCIMIENTO DE LA FED, EUROPA Y SIRIA.

Esta vez hemos escogido dos artículos de George Friendan, quien escrible sobre el atentado de ayer en Londres y que nos refiere que el estuvo allí con su esposa y por ello su nota de reflexión sobre lo que el piensa de estos actos terroristas, es muy interesante.Asimismo George ha escrito sobre la periferia de países en Europa.En rigor, Friedman es un prolífico escritor notable y fundador del interesante Blog Geopolitical Future y es por ello, porque es un verdadero “hardworker”, que hemos puesto sus referencias como un Quote en este post.

Asimismo reproduzco el interesante artículo de The Economist en que se señala que si es cierto que la FED esta subsidiando a los bancos por US$ 12 billones. Y, finalmente, hemos escogido uno muy interesante que muestra un aspecto de lo que viene sucediendo en Siria.

A NEARBY TERROR ATTACK IN LONDON

By George Friedman

Such events force us to think of how close we came to being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

My wife and I are in London this week, and we have spent the last few days enjoying the city.

Yesterday, at about 2 p.m. London time, we thought we would take a walk to the Imperial War Museum. Our hotel is on the corner of Hyde Park, and the museum is across the Thames. We debated whether to go by Parliament over the Westminster Bridge, across the Lambeth Bridge directly to the museum or take a cab. It was chilly, so we took a cab. We thereby avoided a likely encounter with danger. At the same time we were planning our outing, a man was planning what could well have been our death.

The purpose of terror is to force each of us to think that there, but for the grace of God (or the temperature), go I. The night before we had gone to a play in the West End. People crowded the streets. That could have been the place where a car sweeping the sidewalk could have killed many, including us. Tonight, we are going to a concert at the Barbican Centre. There will be crowds. Now I wonder whether someone is planning an attack there too. I’m writing this on Thursday afternoon in London, so by tomorrow we will know.

Police officers stand guard by a cordon around Parliament on March 23, 2017 in London, England. Jack Taylor/Getty Images

Terrorism is a game of probabilities. The probability of any one of us being in the wrong place at the wrong time is very low. But terrorism creates an intimacy between terror and us. It causes us to think of where we were at the time of an attack and how close we came to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Its power is contained in the possibility that the plans of someone unknown to us intersect with our own plans. In the military, they speak of force multipliers. This is the force multiplier of the Islamic terrorist: He compels you to be aware of his power over you. It is his decision whether some will die. I have taken risks in my life, but this is different. Terrorists want to cause a kind of fear that compels you to think of what might have been on an afternoon intended for pleasure.

This has not become corrosive to everyday life yet. It is a quantitative matter. The fewer the attacks, the lower the probability that they will affect you. The higher the number of attacks – even if they are still few – the greater the perception and reality of danger. And as a result, more people are forced to adjust their lives.

Terrorists try to use minimal strength to crush the morale of their enemies. Terrorists are few in number, which is necessary by the covert nature of their activity. The more there are who know each other, the more likely they will be betrayed. And the lone wolf attacker is the least likely to be caught before the attack. The Islamic State and related groups have crafted the most effective form of terror.

They have asked individuals to act with few, if any, collaborators, and to strike without warning, using equipment at hand: a car or a knife. The intent is to let everyone know that their lives are in the hands of invisible enemies. Even though we are not likely to be victims of terrorism, after each attack we are forced to think, “What if I had made a different decision?” In time, each of us will brush up against the possibility. Indeed, my wife and I had spoken, on the way to Covent Garden, of how we would hear screams before we saw an attacking car, and what we might do to save ourselves.

This is the real strength behind IS’ strategy. The lone wolf attack by Muslims is relatively rare. But knowing that Muslims are carrying out such attacks in unpredictable times and that no one can really detect the intentions of others, we wonder what the intent of any Muslims we meet might be after an attack like the one in London. Will he be the agent of our death? The brilliance of this strategy is that it drives a wedge between the Muslim world and the rest. The Muslims are feared, in turn treated unjustly, and the conflict intensifies.

The usual bromide is that we should not take counsel of our fear. I have no idea what that is supposed to mean. Does it mean that I should not dwell on the fact that, by chance, I avoided being caught up in the incident? Does it mean that I should ignore the fact that attacks likely will not be carried out by Swedish grandmothers, but more likely by Muslim males under the age of 30? Should I pretend that this is not a movement of Muslims, by telling myself that most Muslims would not do this? I can’t ignore the fact that some would do this, and that one brushed lightly by our lives on Wednesday. Of course, I should take counsel of my fears. My fears are real and reasonable, and the demand that I should not be afraid is unreasonable.

At the same time, if I take the position that all Muslims are killers, we dramatically increase the chance that the enemy – those Muslims who would kill on a chilly Wednesday afternoon in London – will win. There are 1.6 billion Muslims, and if all were willing to do what the man on Westminster Bridge did, our civilization would be, if not transformed into a nightmare, then constantly afraid. It is the solemn hope of IS that we treat all Muslims as terrorists, to bind together the Islamic world under the jihadist banner.

Some will say that terrorism should not be viewed as Islamic. At this point in history, that is an incomprehensible position. Some will say that all Muslims are potential enemies. That is a prescription for an endless war Euro-American civilization might well lose. In dealing with an enemy, dividing them is the only viable strategy, and the Islamic world already has deep divisions. Muslims are not all alike, and some are hostile to others.

In this, as in all wars, realism and prudence are required. The attacks are part of a movement of Muslims whose numbers are substantial but far from encompassing all of Islam. Our allies must be those Muslims who oppose this movement. Just as the key to undermining communism was the American understanding with communist China, so the key here is allying with Muslim enemies of radical jihadism. If none exist, we will be in trouble. But there are many. However, to apply this strategy, we must admit that this is a war with Muslims. Not all perhaps, but many. As long as we are oblivious to the fact that we are at war with Muslims, the situation is hopeless. As long as we are oblivious to the fact that many Muslims hate the jihadists, we have no strategy. And we must remember that many of the enemies of jihadism do not like us much, either. But as with the communist Chinese, the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

It is odd that a late winter walk in London should end in these thoughts. But then it was Winston Churchill who said, “If Hitler invaded hell I would at least make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.” Some in England said Germany should not be confused with Nazism. Others said all Germans should be annihilated. Churchill regarded the first statement as fatuous and the second as brutishly stupid.

In the meantime, we are in a strange but real war, and a walk in Covent Garden now must involve a discussion of what to do if death approaches.

IS THE FEDERAL RESERVE GIVING BANKS A $12BN SUBSIDY?

By: The Economist

Or is the interest the Fed pays them a vital monetary tool that benefits the taxpayer?

Every time the Federal Reserve has raised rates since the financial crisis, as it did on March 15th, it has done so in part by increasing “Interest On Excess Reserves” (IOER). This obscure policy rate is surprisingly controversial. Jeb Hensarling, the Republican chair of the congressional committee that oversees the Fed, has called it a “subsidy” to some of the largest banks in America.

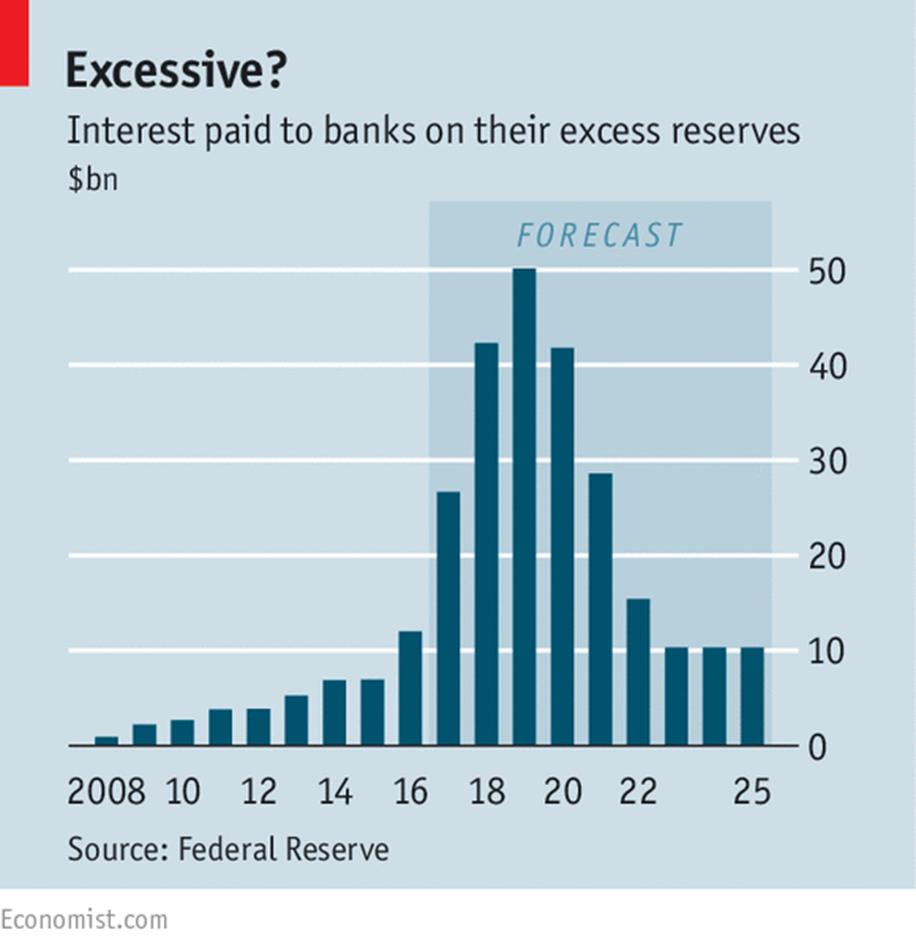

To understand the argument, consider the Fed’s year-end financial statement. In 2016 it earned $111.1bn in interest income on its vast portfolio of securities. But it also paid JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and other mostly big banks $12bn in interest on excess cash deposited at regional Federal Reserve banks. Such IOER payments are both woefully unpopular and critical to the Fed’s monetary policy.

Over a decade ago, to give the Fed better control of short-term interest rates, Congress authorised it to pay interest on funds in excess of those banks need to meet reserve requirements. The policy was first used during the financial crisis in 2008. But today, IOER is the Fed’s primary monetary-policy tool, essential to its setting of the Federal Funds rate.

IOER has drawn fierce flak from Congress. If banks can park their money at the Fed, they seem to have less incentive to lend to firms and consumers. About half of all excess reserves are held by America’s 25 largest banks, with a third, to Congress’s horror, held by foreign banks. The two groups earn roughly 85% of the Fed’s interest payment.

Many analysts argue that these interest payments—amounting to less than 2% of the banks’ total income—are in fact trivial. They claim banks would rather earn higher returns elsewhere, and that the real winner from the current arrangement is the government. The excess reserves help finance the Fed’s $4.5trn balance-sheet, which generated almost eight times more income for the Treasury in 2016 than was paid out in interest.

This debate is likely to intensify. American banks hold over $2.1trn in excess reserves. As rates rise, the cost of paying interest on them will climb—to $27bn this year, according to Fed projections and $50bn by 2019 (see chart). That may be too much. Mark Calabria of the Cato Institute, a think-tank, says that anything that can be tagged as “paying banks $50bn a year not to lend” will be “politically unsustainable”.

Meddling with the arrangement might cost even more. Without IOER, banks would try to lend their excess reserves to each other, so short-term interest rates would collapse. To keep control of monetary policy—and avert a surge in inflation—the Fed would have to sell assets rapidly to withdraw reserves from the system. The disruption, a recent analysis concluded, could prove “extremely costly to taxpayers”.

NOTES FROM EUROPE'S PERIPHERY

By George Friedman

Both ends of the Continent's periphery are shifting away from the core.

I’m writing this from London and heading from here to Poland and Hungary. This seems like a trip from one Europe to the other. In fact, at this point in history, these places have a great deal in common. They are each on Europe’s periphery, trying to define their relationship to Europe and trying to cope with the radical implications of the right to national self-determination.

Europe’s core since the late 19th century has been Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. In some ways, this was Charlemagne’s Europe, which was the organizing core of the European Peninsula. These countries, with the addition of Italy and Luxembourg, also established the European Coal and Steel Community, which eventually evolved into the European Union.

Together they account for a substantial proportion of Europe’s wealth.

Europe’s periphery consists of the countries and regions that surround this core: Scandinavia, the British Isles, Iberia, the Balkans and what used to be called Eastern Europe. A strong argument can be made that Italy also should be considered part of the periphery. Italy had been the center of a great Mediterranean empire in the distant past, but it was never part of the Europe that Charlemagne created.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon arrives for First Minister’s Questions with deputy John Swinney and Brexit minister Mike Russell inside the Scottish Parliament on March 16, 2017 in Edinburgh, Scotland. The first minister faced questions in parliament for the first time since announcing her intentions to hold a second Scottish independence referendum following the U.K.’s decision to back Brexit and leave the European Union. Jeff J. Mitchell/Getty Images

The European Union tried to envelop the periphery and the core into one structure. In theory, it was to be a union of equals, but increasingly it has become a periphery rotating around a core. Within the center, the periphery rotated around the true core – Germany. This pattern remained until 2008 when the rotation became less of an orbit than a centrifugal force.

In England – and I choose that term to distinguish it from Britain – the centrifugal movement is now palpable, and the movement away from the center shows every prospect of shattering Britain. I was at a financial conference in London where the major issue, reasonably, was the future of the economy.

While important, that is not the most significant question facing Britain. Far more important than Brexit’s financial implications are whether Scotland will end its union with England and what Northern Ireland will do.

The idea of Scottish independence is rooted in the fact that the Scots see themselves as a different nation from the English. There has always been an undercurrent of Scottish nationalism that did not quite manifest as a very serious movement until now. Part of the Scottish argument for independence pivots on economics. But the more important force is the one sweeping Europe: nationalism and self-determination. The Scots want to be Scots because they are Scottish. It is hard to build this into an economic optimization model, but that is the weakness of economics.

The Scottish question arose before Brexit, and that vote allowed the issue to reignite. The Scots voted to remain part of Britain by a relatively small margin, and they believe that another round will do it.

The financial community is calculating the financial impact of such a move. But the political significance strikes me as more important.

As for Northern Ireland, it has long been torn by nationalism. It is divided by Catholics, who identify with the Irish Republic, and Protestants, many of English origin, who identify with England. They waged a bloody civil war, a follow-on to a bloody rebellion that had waxed and waned for centuries.

After nationalist sentiments were at least temporarily quieted, the Brexit debate introduced economic questions that could reignite the struggle for Irish vs. English loyalties.

This leads to a vital geopolitical issue. If Scotland re-emerges as an independent nation, and if English power is expelled from Northern Ireland, this would not only turn back the clock centuries, but other possibilities would emerge as well. One of the reasons the English sought union with Scotland was to make it impossible for foreign powers, particularly the French, to threaten England from the rear.

This possibility seems archaic, but it actually isn’t. Europe has major, systemic wars every century.

At the moment, such a war seems unthinkable, but nothing is unthinkable in Europe. The European Union is weakening and fragmenting. And in the broader global framework, this scenario is even more likely. What an independent Scotland’s foreign policy would look like is unknown, and it may remain in some sort of confederation with England. But if not, Scotland would return to its old stance. It is weaker than England and, therefore, needs a stronger ally.

England will see this stronger ally as a potential threat. Therefore, full independence and an evolution of tensions in Europe or globally could reasonably reignite a very old set of tensions to England’s north. While some assert their right to national self-determination, others will challenge that right, and that creates geopolitical complexities, to say the least.

In traveling to another part of Europe’s periphery, I will find a variation on this theme. Long ago, Poland and Hungary were both significant regional powers. In recent centuries, both lost their sovereignty at various points. Poland was divided by the Romanov, Habsburg and Hohenzollern dynasties. Hungary was part of the Habsburg Empire. After World War I, collapsing empires freed both countries, but that freedom lasted only as long as it took Germany to re-emerge. Poland was occupied by Germany and the Soviet Union. Hungary remained free, with limited freedom of action because of Germany’s power, until the Germans occupied it in 1944. After World War II, it had formal sovereignty but was actually controlled from Moscow.

Given this past, the likelihood of both nations dissolving under pressure was extremely high.

Neither did, and both gained full sovereignty in 1989 when the Soviet Union withdrew from Germany.

Almost immediately, Poland and Hungary were drawn into the European Union and NATO.

Their primary motive was to build their economies and retain their national independence, particularly if Russia re-emerged as a power. In that sense, they promptly traded elements of their sovereignty for peace and prosperity. They would remain Poles and Hungarians but also become Europeans.

It was much the same deal as the Scots made and the Irish refused. The Scots made a deal to retain their identity but not autonomy. The Irish fought to keep both. Poland and Hungary willingly entered into Europe for two reasons. First, after experiencing fascism and communism, one of their priorities was to develop a political culture that would render them immune from the contagion. In their view, Europe had freed itself from fascism and guaranteed this freedom in an institutionalized form in the EU. The bloc would protect both countries, or so they thought.

Second, the price for entering Europe would be low. They could enjoy the benefits without giving up nation self-determination, and that meant they remained sovereign.

After 2008, Europe began its ongoing move to the right and nationalism. Eastern Europe started this movement first by electing Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and then electing a similar government in Poland a few months later. This created a strain between these countries and the EU. In the British Isles, England and Scotland sought to pull away. But Eastern European countries were pushed away.

The Polish and Hungarian governments were elected by large margins in elections mostly free of fraud. No one challenged the elections’ legitimacy. However, the EU challenged the policies of both governments on a range of constitutional shifts concerning the judiciary and the media.

Neither government hid their general intentions. The voters knew and wanted what they were voting for.

However, the same thing these countries hoped to gain from joining the EU, immunization against fascism, now collided with the EU’s attempt to protect its general ideology. From the EU’s perspective, what the Poles and Hungarians were doing went beyond the pale of acceptable liberal democratic behavior. From the standpoint of Hungary and Poland, they had adhered to the heart of liberal democratic behavior: Their governments had won free elections.

In challenging the right of an elected government to chart its course, it was the EU that was violating liberal democratic values.

The exercise in political theory is of interest, but the heart of what I am arguing is that just as the British periphery is fragmenting, the Eastern European periphery is also fragmenting.

Some regimes are now pulling away from other countries and the EU; other regimes are drawing closer. This fragmentation has critical geopolitical consequences in the short term. As the EU alienates Poland and Hungary, further fragmentation will take place as these two countries try to find a balance between Europe and Russia, rather than simply being committed to the center, particularly Germany.

It is odd to sit in London and think of the similarities between the English and the Poles and Hungarians, but in fact, they are in the same condition. They are pulling away –some would say being repelled away – from the EU and facing the geopolitical consequences. For Britain, it is a return to the configuration of the 17th century. Meanwhile Poland and Hungary are trying to establish their sovereignty outside the construct of a multinational entity. The western and eastern peripheries are undergoing not only the first experience of fragmentation but also post-fragmentation of the geopolitical system.

The EU was an attempt to freeze history in peace and prosperity. The prosperity having failed, the question of peace is now on the table. If peace fails, then the geopolitical reality shifts, and history continues.

THE EMERGING POST-CALIPHATE SYRIAN BATTLESPACE

By Eric Czuleger

Conflicting regional and international forces are vying for control.

The Islamic State is weakening, which indicates that we should examine the future of the declining caliphate’s sphere of influence. A weak IS will create an opportunity for other factions backed by their respective regional powers to fill the emerging power vacuum. The United States and Russia are trying to limit their exposure and secure their influence in the Middle East, but the definitive actors in Syria will be exerting influence within its borders. Geopolitical Futures has identified four major powers in the Middle East: Turkey, Israel, Iran and Saudi Arabia. The first three have a deep interest in how the different factions will reposition themselves in the post-caliphate battlespace. Turkey, Iran and Israel are already preparing for this, and we need to examine how these dynamics will affect the Levantine region.

Since last Friday, a series of events has unfolded that provides a clear window into the imperatives of major regional powers in Syria. Israel utilized air power to launch an assault on a Hezbollah arms shipment outside Palmyra, and conflicting reports have surfaced about Russian involvement with Kurdish forces in Afrin district. These reports necessitate a closer look at the goals of regional players within the Islamic State’s declining sphere of influence.

A Syrian rebel walks past graves in the rebel-held southern city of Daraa, on March 20, 2017. MOHAMAD ABAZEED/AFP/Getty Images

We will begin with Turkey’s regional imperatives. Sharing a long border with Syria leaves Turkey exposed to the spillover of the various wars taking place in the Syrian battle box. The Turks are concerned that the Syrian Kurds will be major beneficiaries of IS’ territorial losses.

Ankara is already at odds with Washington over U.S. reliance on the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces. Recently, a spokesman for the People’s Protection Units (YPG) fed a story to Western media that Russia has been lending support to the Syrian Kurds through a base in northwestern Syria. Russia has denied these claims, and the United States has kept quiet. This tells us less about Russia and the U.S. than it does about the narrative the Kurds are trying to construct. They are trying to show they are an internationally supported fighting force and a legitimate state actor. The YPG is trying to appear more relevant in the face of its waning usefulness.

The Kurds have outlived their utility to the U.S., and they were never useful to Russia. In the eyes of both Russia and the United States, Turkey will have to take on more responsibility in Syria to secure its borders. The Kurds were a viable instrument to make territorial gains on Islamic State, but they are not a viable long-term partner for the U.S. or Russia. They are, however, a powerful lever in motivating Turkey.

As is often the case in geopolitics, opportunity exists alongside crisis. Turkey’s goal is to suppress Kurdish ambition, and pursuant to that, Ankara has entered ground troops into northern Syria. Turkish troop numbers are too low to act definitively, and they are attempting to achieve their goals with minimal exposure. While Turkey understands that it will not be rid of the Syrian Kurds, its ground troops are working to prevent Kurdish influence from growing.

Turkey’s imperative necessitates achieving and maintaining a level of regional control in Syria.

Given that Turkish troops are already on the ground in Syria, it is likely that Turkey will fill a portion of the post-caliphate power vacuum. However, Turkey is not the only rising Middle Eastern power that has ambitions in the Levant. Iran is also weighing how to proceed as IS loses its territorial holdings.

The Iranian-backed Shiite Islamist movement Hezbollah viewed the armed uprising in Syria as an existential threat. The regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is a crucial actor in enabling Iranian support for Hezbollah. The regime allows Tehran to provide material and economic support to its proxy in Lebanon. Had the Syrian regime been overthrown, the pro-Iranian Shiite state in Iraq would have become vulnerable as well to a cross-border Sunni movement. This is why Iran has continued to support the Assad regime and the Syrian Arab Army throughout the crisis in order to maintain its sphere of influence on its western flank.

Between the regime’s recent victory over rebels in Aleppo and the impending collapse of the IS capital in Raqqa, Iran is hoping to see a major return on its military, economic and political investments in Syria since 2011. More than that, Hezbollah is looking forward to emerging victoriously from the bloody civil war in which they are currently mired. Hezbollah and Iran will benefit from the decline of the Islamic State, but those gains serve to unnerve Israel.

From Israel’s point of view, Iranian influence in Syria through Hezbollah must be stopped. While steering clear of direct involvement, Israel has kept a close eye on the evolving Syrian civil war, especially in terms of how the conflict could potentially allow Hezbollah to become a bigger threat to Israel. Various Sunni jihadists (IS, al-Qaida and most of the rebel groups) are rhetorical enemies of Israel, but in practice, they have more pressing objectives. Hezbollah is an institutionalized force that has shown an ability to disrupt Israel, as in the 2006 war. This is why the Israeli Defense Forces have from time to time carried out airstrikes in Syria to ensure that Hezbollah does not get its hands on more sophisticated weaponry, especially missiles that can threaten Israeli air superiority.

To this end, Israel recently carried out airstrikes on a weapons shipment convoy outside Palmyra. This is the deepest Israeli strike to date in Syria. However, the attack’s target was an arms shipment headed to Hezbollah’s stronghold in Lebanon. While Israel does not want to fill the oncoming power vacuum, it has to manage threats from the Iran-allied Hezbollah. Hezbollah already occupies considerable space in Lebanon to the north of Israel and has recently proved it is able to use Syrian space to arm itself. Israel will continue to manage threats from afar while keeping tabs on Hezbollah’s presence in Syria.

Islamic State is in danger of losing its territorial holdings in Syria and Iraq. This does not, however, mean an end to conflict in the region, nor does it mean an end to Sunni Islamist extremism. GPF recently reported on bombings in Damascus carried out by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the third incarnation of Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaida. Different militias are engaging in an intra-Sunni struggle to emerge as the jihadist vanguard in the wake of a weakened Islamic State. However, the non-Sunni forces will play a greater role in shaping the future outlook of the Syrian battlespace. These include the Kurds, the Syrian regime and Hezbollah. All of these powers will in turn shape the behavior of the main regional stakeholders, Turkey, Iran and Israel.

If and when IS is decimated, it will only end the current episode of the war radiating out of Syria and Iraq. We have discussed some of the dynamics emerging from a weakened Islamic State, but the oncoming power vacuum will inevitably be filled by conflicting regional and international forces vying for control of the post-caliphate Middle East.

______________________________________________________________________________QUOTE