EL EXPERIMENTO MONETARIO MAS RADICAL

TAL PARECE: QUE NO ESTA FUNCIONANDO COMO SE PREVEIA QUE LO HARIA

POR: Dennis Falvy

Antes de entrar en materia, permítaseme una digresión: Con la publicación de este post en su idioma original; hemos tomado la decisión de sólo seleccionar uno de ellos como máximo diario, debido a consultas, sentires, pareceres y consejos.

La opulencia de la información es brutal y la selección de ella es un trabajo arduo. Así que escogeremos , la que a nuestro criterio es lo más actualizado y de calidad y utilizaremos nuestros pies de página (Quotes&Unquotes) a fin de sugerirles las que a nuestro criterio, si ustedes lo tienen a bien, busquen los artículos en el internet.

Si hay un post alternativo , relativamente pequeño, lo copiaremos en los pies de página. Asimismo y si lo amerita el autor, haremos una reseña del mismo. Y, finalmente, respetaremos escrupulosamente el idioma original; es decir el inglés, advirtiendo nuevamente que con un click en el lado derecho de su mouse puesto en alguna parte del texto en cuestión, podrán ustedes tener la traducción al castellano. Obviamente la misma no es de las mejores, pero ayuda al menos a comprender en un buen porcentaje, lo que el artículo original muestra.

Este post que publicamos hoy es extraído del Wall Street Journal y a nuestro criterio es sumamente aleccionador e interesante, ya que le hace al controvertido mundo de la “Política Monetaria”; la que se está usando intensivamente a partir de la crisis del año 2,008;es decir la denominada “Sub prime” y de una manera inmensa por los Bancos Centrales de los países grandes en proporciones e intervenciones en los mercados jamás visto en la historia financiera del mundo que conocemos.

De esto hay múltiples opiniones y hay algo que siempre debe quedar claro: Nadie tiene una “ eficiente” bola de cristal, pues el mundo es multivariable.No existe el riesgo cero en nada. Somos seres humanos finitos. La ciencia avanza de una manera impresionante. Y la era robótica se asoma en una denominada “ Cuarta Revolución Industrial”, la que tiene sus preferencias y sus restricciones. Amén de que muchos avizoran un reventazón de burbuja en Wall Street y los mercados financieros aledaños y asimismo lo del Brexit, lo de Trump, las guerras en Siria y otros lugares y los cambios de preferencias de las gentes contra el establishment, configuran que cada vez el análisis de lo que hay en el mercado periodístico, al menos, tiene que ser atendido y entendido , en sus perspectivas correspondientes.

Ello tal vez no es suficiente para un mejor rendimiento profesional o para estar informado cabalmente de lo que sucede es un mundo globalizado e interconectado de las finanzas . Pero sin duda ayuda. Y esa es mi sana intención, sin absolutamente nada bajo la mesa. El compartir con ustedes amigos lectores una mejora de la información y de su propio criterio; pues vaya que las redes también tienen su lado malo. A veces asimismo mal informan y sesgan en función de intereses particulares y de otra magnitud.

Aquí el post seleccionado el día de hoy , gracias a la colaboración sistemática y extraordinaria de un excelente amigo , que quiere permanecer en el anonimato y ello se respeta.

THE WORLD’S MOST RADICAL EXPERIMENT IN MONETARY POLICY ISN’T WORKING

A generation of Japanese accustomed to falling prices have diminished the impact of negative interest rates and other stimulus policies that were supposed to spur wage and price increases; ‘people love to save’

BY JOHN LYONS AND MIHO INADA

John Lyons Reporter, The Wall Street Journal is a senior reporter based in Hong Kong, covering regional economic themes and the city of Hong Kong SAR. Previously, John spent 12 years with the journal covering Latin America, and has also called São Paulo, México D.F. and Buenos Aires home.

During Japan’s go-go 1980s, Hiromi Shibata once blew a month’s salary on a cashmere coat, wore it a few times, then retired it. Today, her daughter’s idea of a shopping spree is scrounging through her mom’s closet in Shizuoka, a provincial capital.

“About a third of my wardrobe is hand-me-downs from my mom,” says 26-year-old Nanako Shibata, who lives in Tokyo. To save on the 112-mile trip home, she rides the bus instead of the speedy bullet train, once a symbol of Japan’s rise.

The U.S. appears to be leading other parts of the globe out of an extended era where central banks relied heavily on low and negative interest rates and stimulus to jump-start growth and keep prices from falling. The Federal Reserve has raised U.S. interest rates, and the European Central Bank is considering easing its stimulus.

Japan remains definitively stuck, despite a long and aggressive experiment with ultralow rates. A quarter-century after its property bubble burst, a penny-pinching generation has come of age knowing only economic malaise, stagnant wages and deflation—a condition where prices fall instead of rise.

The belief that deflation will continue has become so ingrained it has presented seemingly insurmountable challenges to monetary policy, a lesson for other countries that are traveling a similar path.

“It is hard to change the deflationary mind-set even with radical policies,” says Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asia economics for HSBC. “I would argue Japan will remain in its funk and will remain there for many years.”

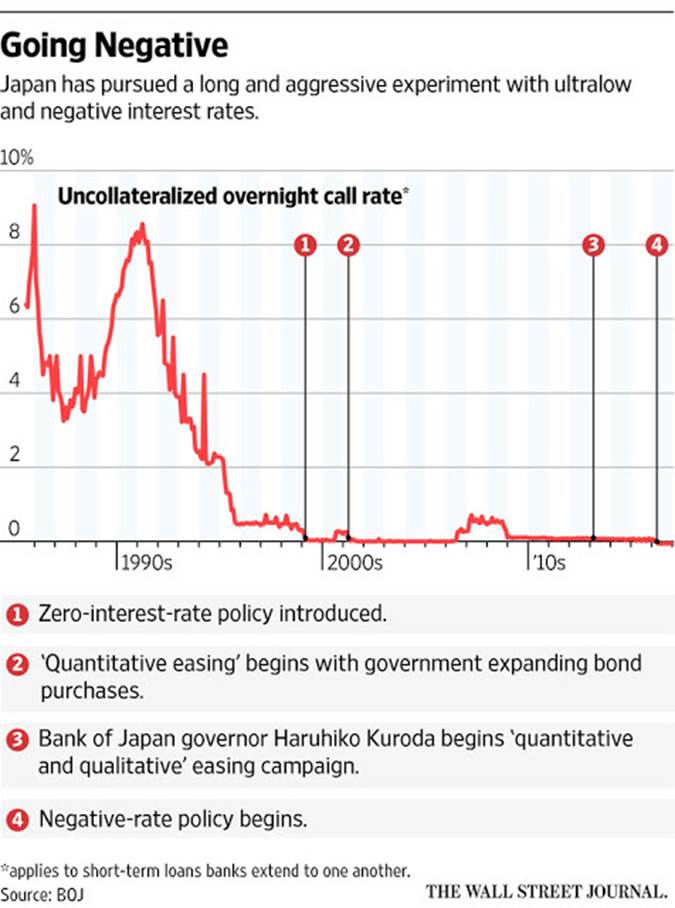

Japan is nearly four years into a Central Bank stimulus effort involving printing trillions of yen and guiding interest rates into negative territory, perhaps the globe’s most aggressive such efforts under way. Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s shock-and-awe stimulus, launched in April 2013, fizzled after a short-lived spurt of growth and rising prices. Japan fell back into deflation last year. More recently, the inflation rate has been bouncing around near zero.

In November, Mr. Kuroda postponed his goal of reaching 2% inflation, all but admitting he is out of ideas. He said in a series of speeches last year that an entrenched “deflationary mind-set” stifled hope that wages or prices will rise, limiting the impact of monetary policies such as negative rates. Mr. Kuroda declined to comment through a spokesman.

Japan’s inflation rate has ticked above zero in recent months, which economists attribute to the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, a stronger dollar and higher oil prices—not economic fundamentals in Japan. Few see Japan returning to robust growth and rising prices.

Deflation is bad for an economy because it undermines economic growth. Businesses earn less, so they invest less, cut wages and stop hiring. Amid the economic uncertainty, consumers stop spending, furthering the downward spiral.

The idea behind ultralow rates is that they jolt consumers and businesses into spending by kindling inflation. But Japan’s deflationary expectations have become so routine that consumers and businesses refrain from spending no matter how low the central bank goes. There is evidence, in fact, that rock-bottom rates are backfiring by frightening consumers into saving for perilous economic times, not spending.

In an era of central-bank improvisation, no other nation has pushed the envelope as much. The Bank of Japan was the first to lower its benchmark rate to near zero in 1999, long before Europe, the U.K. and the U.S. did so in response to the 2008 financial crisis. In 2001, Japan began flooding its financial system with cash to try to spur inflation and growth, a practice called quantitative easing that was later adopted in the West.

Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda has said a ‘deflationary mind-set’ is hampering the nation’s economy. Photo: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg News

Mr. Kuroda in 2013 began pumping so much money into the financial system—eventually around $700 billion a year—that some investors worried hyperinflation or asset bubbles would form. That hasn’t happened. Last year, the Bank of Japan followed the European Central Bank in guiding rates into negative territory, a radical attempt to force banks to lend more money by making it costly if they don’t.

Japan’s predicament today was almost unthinkable during its 1980s boom, when Japanese tycoons bought trophy properties such as New York’s Rockefeller Center and Tokyo real-estate prices were the world’s highest. In 1989, Japan initiated interest-rate hikes that popped real-estate and stock-market bubbles.

Since then, annual growth has averaged less than 1% amid periodic recessions. Prices began falling in the late 1990s.

Japan’s economy dropped to the world’s third-largest after fast-growing China surpassed it as No. 2. The Nikkei stock-market average is around half its 1989 peak. Property prices have fallen broadly for a quarter of a century.

Frozen-dessert maker Akagi Nyugyo ran an apologetic advertisement last year after implementing a 9 cent increase, its first in 25 years. Japanese companies are sitting on nearly $2 trillion in cash, idle money that officials contend should be invested in Japan.

The deflationary landscape is deeply imprinted on the 20 million Japanese between ages 20 and 34 who grew up after prices started falling. Wage increases, rising stocks or banks that pay decent interest on deposits are all hypotheticals to them. They live in a world where anything they buy today might be had for less tomorrow. Their instinct is to do the safe thing and economize.

They reject the consumerism of their parents’ generation as excess. Some live with roommates in group homes, a new phenomenon for Japan, and dine on $3 beef bowls. If they spend on anything, it is travel. In a deflationary society, experiences don’t lose value, while anything you buy does.

Some older Japanese who knew the privations of the postwar years see a worrisome lack of ambition in younger people. Japan uses the term “neets” to describe young people “not in education, employment or training,” while “freeters” work unstable part-time or contract jobs. Japanese “parasite singles” never leave their parents’ home, and women complain about “herbivore men” uninterested in the opposite sex.

“Their problem is they are too comfortable,” says Heizo Takenaka, a former economy minister.

“Their expectations are low. We wanted to own the excellent cars. But they don’t seem to want to.”

Many economists believed the Bank of Japan’s 2013 stimulus would be enough to jolt the nation out of its downward spiral of weak growth and falling prices. Mr. Kuroda and others in Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government point to an initial burst of inflation and growth as signs the stimulus will eventually work. Others say the monetary policies worked until they were undermined by a 2014 sales-tax increase.

A Bank of Japan survey in October found only 5% of respondents planned to spend more next year, while 48% intended to cut.

Many Japanese millennials are dedicated to economizing, eating at places like Yoshinoya, a fast-food chain that specializes in inexpensive beef bowls. Photo: Jeremie Souteyrat for The Wall Street Journal

Keita Kameyama, a 30-year-old civil servant in Kagawa, a rural province, has been saving around 25% of his $40,000 salary each year to eventually marry his longtime girlfriend. He lives at home with his mother, drives an old Honda and rarely shops.

The central bank’s stimulus measures had no effect on Mr. Kameyama’s spending. He still salts away his money in plain-vanilla bank accounts. He fears Japan’s long stagnation will wipe out his pension, and worries he won’t have enough money to care for his mother—a growing concern in a country with twice as many people over 60 than between 20 and 34.