LAS TRES VIDAS DE ALAN GREENSPAN

PERO LA TERCERA NO VA A REDIMIR LA SEGUNDA

Por:Dennis Falvy

En el Blog Dollar Colapse se publica este interesante post sobre Greenspan. Como se conoce ;Alan Greenspan (nacido en Nueva York el 6 de marzo de 1926) es un economista estadounidense de origen judío que fue presidente de la Reserva Federal de EE. UU. desde el 11 de agosto de 1987 hasta el 1 de febrero de 2006. Fue nominado al puesto por los presidentes Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton y George W. Bush.

Greenspan nació en el vecindario de Washington Heights (Manhattan), en la ciudad de Nueva York. Su padre, Herbert Greenspan, procedía de una familia judía de origen rumano, mientras que su madre, Rose Goldsmith, descendía de una familia de húngaros judíos. Alan Greenspan fue hijo único.

Greenspan domina el clarinete y el saxofón, habiendo llegado a tocar con Stan Getz cuando coincidieron en la universidad. Estudió clarinete en la Juilliard School desde 1943 hasta 1944, momento en el que se unió a un grupo profesional de jazz. Volvió a la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU) en 1945, obteniendo en 1948 el Bachelor of Science summa cum laude en economía. Así mismo, en 1950 conseguiría el Master of Arts, también en economía.

Greenspan acudiría a la Universidad de Columbia, tratando de realizar estudios de economía avanzada. Los estudios de Greenspan serían tutelados por Arthur Burns, futuro Presidente de la Reserva Federal, cuyos planteamientos se centraban en denunciar los peligros de la inflación.

En 1977, la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU) le concedería el doctorado en economía. Su discurso no está disponible en la NYU desde que fue retirado a petición del propio Greenspan, en 1987, cuando se convirtió en presidente de la Reserva Federal.

No obstante, se ha encontrado una copia, en cuya introducción se incluye una reflexión sobre el incremento de los precios de la vivienda, y su efecto en el consumo; incluso se anticipaba la aparición de una creciente burbuja inmobiliaria.

En 1952, Greenspan conoció a Ayn Rand, escritora y filósofa creadora del Objetivismo. Greenspan estuvo varios años en el círculo interno del llamado «Colectivo objetivista». Los críticos de izquierdas de Greenspan apuntan que sus políticas antiinflacionistas son consecuencia de sus años de implicación con un movimiento que apoya sin reservas la vuelta a lo que llaman el sound money e incluso el regreso al patrón oro. La evaluación que se hace de Greenspan desde el movimiento objetivista es muy ambivalente. Leonard Peikoff ha criticado abiertamente sus políticas al frente de la Reserva Federal, pero otros objetivistas apuntan a que Greenspan trató de salvar el sistema monetario norteamericano «desde dentro», tratando que fuera lo menos deshonesto posible.

En su libro The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World, publicado en septiembre de 2007, Greenspan ofrece su opinión de que la guerra en Irak se debió al petróleo, escribiendo: «me entristece que sea políticamente inconveniente reconocer lo que todos sabemos: la guerra en Irak se trata inmensamente sobre petróleo». Greenspan ha aclarado más tarde este comentario en una entrevista. En dicha entrevista, Greenspan afirmó: «Yo no me refería a que ese fuese el motivo de la administración. Yo sólo digo que si alguien me preguntara "¿somos afortunados de haber sacado a Saddam?" Yo diría que fue esencial».

En el inicio de la crisis económica de 2008, se acusó a Alan Greenspan de haber permitido durante su mandato la proliferación de los denominados derivados financieros (como las opciones, futuros, CFD, etc. que permiten obtener una mayor ganancia, pero también una pérdida más grande si el activo subyacente cambia de tendencia imprevistamente), que fueron la causa final de la crisis, y no haber permitido su regulación. El banquero Felix G. Rohatyn advirtió del peligro de estas operaciones calificándolas de "bombas de hidrógeno financieras", y Warren Buffett como "armas financieras de destrucción masiva que entrañan peligros que, aunque ahora estén latentes, pueden llegar a ser mortíferos". No obstante, Greenspan afirmó ante el Senado de Estados Unidos en 2003 que "lo que hemos visto a lo largo de los años en el mercado es que los derivados han sido un vehículo extraordinariamente útil para transferir el riesgo de las personas que no deberían asumirlo a aquellas que están dispuestas y son capaces de hacerlo".

Durante la crisis de 2008, mantuvo sus posiciones, considerando que la misma se producía una vez cada cien años y el problema no eran los contratos de derivados, sino la avaricia. No obstante, Frank Partnoy, catedrático de la Universidad de San Diego afirmó que estaba "claro que los derivados son un punto central de la crisis y él era uno de los principales defensores de la liberalización de los derivados". En opinión de muchos economistas, de haber actuado de otra manera Greenspan, la crisis se hubiera mitigado.

THE THREE LIVES OF ALAN GREENSPAN AND WHY THE THIRD WON´T REDEEM THE SECOND .

When the history of these times is written, former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan will be one of the major villains, but also one of the greatest mysteries. This is so because he has, in effect, been three different people.

He began public life brilliantly, as a libertarian thinker who said some compelling and accurate things about gold and its role in the world. An example from 1966:

An almost hysterical antagonism toward the gold standard is one issue which unites statists of all persuasions. They seem to sense – perhaps more clearly and subtly than many consistent defenders of laissez-faire – that gold and economic freedom are inseparable, that the gold standard is an instrument of laissez-faire and that each implies and requires the other…

…In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold [in 1934 under FDR]. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods. The financial policy of the welfare state requires that there be no way for the owners of wealth to protect themselves.

This is the shabby secret of the welfare statists’ tirades against gold. Deficit spending is simply a scheme for the confiscation of wealth. Gold stands in the way of this insidious process. It stands as a protector of property rights. If one grasps this, one has no difficulty in understanding the statists’ antagonism toward the gold standard.

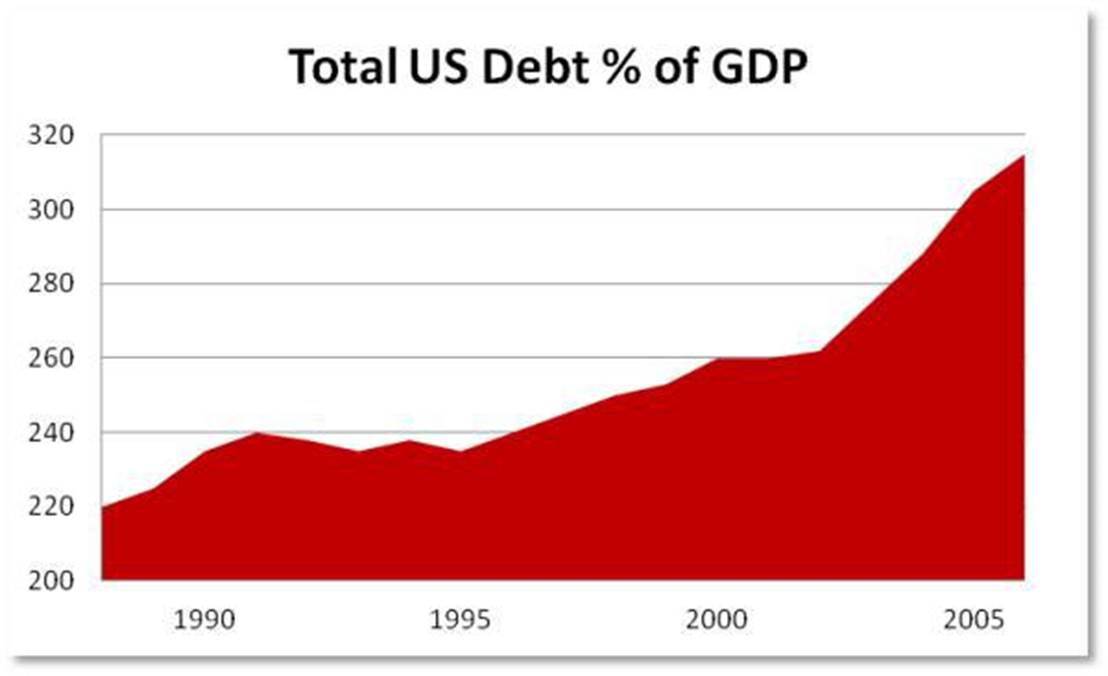

Awesome, right? But when put in charge of the Federal Reserve in the late 1980s, instead of applying the above wisdom — by for instance limiting the bank’s interference in the private sector and letting market forces determine winners and losers — he did a full 180, intervening in every crisis, creating new currency with abandon, and generally behaving like his old ideological enemies, the Keynesians. Not surprisingly, debt soared during his long tenure.

Along the way he was instrumental in preventing regulation of credit default swaps and other derivatives that nearly blew up the system in 2008. His view of those instruments:

The reason that growth has continued despite adversity, or perhaps because of it, is that these new financial instruments are an increasingly important vehicle for unbundling risks. These instruments enhance the ability to differentiate risk and allocate it to those investors most able and willing to take it. This unbundling improves the ability of the market to engender a set of product and asset prices far more calibrated to the value preferences of consumers than was possible before derivative markets were developed.

The product and asset price signals enable entrepreneurs to finely allocate real capital facilities to produce those goods and services most valued by consumers, a process that has undoubtedly improved national productivity growth and standards of living.

He cut interest rates to near-zero in the early 2000s, igniting the housing bubble – which he was unable to detect along the way. He even made it into the dictionary, as the “Greenspan put” became the term for government bailing out its Wall Street benefactors.

From this the leveraged speculating community learned that no risk was too egregious and no profit too large, because government – that is, the Fed – had eliminated all the worst-case scenarios. Put another way, under Greenspan profit was privatized but loss was socialized.